While the worldwide strategy on leprosy to date has focused on disease control, disability and stigma are the main concerns of people affected by leprosy. A large emphasis on leprosy by NGOs in Bangladesh, has yielded quality longitudinal data regarding physical impairments due to leprosy, and a number of important studies on nerve function impairment due to leprosy, have been published. Some of these data and studies are summarised here, and their potential benefit in understanding and preventing leprosy-related disability is discussed. The rate of visible physical impairment (WHO Grade 2 disability) among people newly affected by leprosy in Bangladesh was nearly 9% in 2003, significantly higher than the target of 5%. There is strong evidence that such impairments can be expected where diagnosis is delayed. New nerve function impairment in patients on treatment, may be expected to occur in over 60% of the highest risk group within two years. New nerve damage is often clinically silent in early stages, but is not routinely checked for in many integrated leprosy control programmes.

On this basis, it appears that there is significant under-detection and/or under-reporting of leprosy-related disability at diagnosis and subsequently, especially where leprosy is fully integrated into general health programmes. The measurement of activity and participation limitation due to leprosy in Bangladesh, as elsewhere, has been limited thus far. Progress in development of community-based responses with and by people affected and disabled by leprosy has been modest, though significant efforts are underway.

INTRODUCTION

Leprosy is a chronic mycobacterial disease with primarily skin and nerve manifestations. Damage to peripheral nerves occurs both as a direct result of invasion of Schwann cells by the causative agent "Mycobacterium leprae" and subsequent immunological reaction to the same (1). Damage to the posterior tibeal, ulnar, median, facial, lateral popliteal, trigeminal, and radial nerves is the main cause of physical impairment and resulting limitation of physical activities and social participation in people affected by leprosy (2). Sensory function loss is a cause of repeated injury, ulceration and limb shortening. Corneal sensation loss may result in unrecognised corneal injury and significant visual loss. Motor function loss is a cause of finger and toe clawing, failure of eye closure (lagophthalmos), and foot and wrist drop.

Notwithstanding the wide variety of physical impairments and associated disabilities resulting from leprosy, the prevailing strategy in leprosy is focused on disease control through the systematic implementation of treatment of infection by "Mycobacterium leprae" with Multi- Drug Therapy (MDT). This is in part because early case detection and treatment reduces the incidence of physical impairment at diagnosis. In addition, it is hoped that through intense control efforts, the overall incidence of leprosy will be reduced by reducing the reservoir of infection. This reservoir is believed to be confined to those untreated affected persons who have little immunological response, though this assumption has been recently questioned (3,4). These 'lepromatous' cases of leprosy represent around 15-40% of the total caseload. Good case-holding practices also facilitate the early detection and treatment of nerve function impairment in field programmes (5,6).

While most countries treat leprosy in a fully integrated way within the public health system, caring for leprosy patients by general multi-purpose health staff, Bangladesh retains a specialist arm to leprosy and TB control. The Health authorities continue to encourage a very active role by non-Government Organisations (NGOs) in this regard. The resultant excellent record keeping and long-standing close collaboration with NGOs makes Bangladesh an important case study in regard to leprosy control. NGOs have been primarily responsible for leprosy treatment and care for around 75% of new leprosy cases since 1995, and The Leprosy Mission alone, cares for 50%, over 4000 new cases annually (7).

The focus on leprosy by NGOs in Bangladesh, means that routine and reliable longitudinal statistical data on disability in leprosy are available, which is not the case elsewhere in the world on such a large scale. Several seminal research projects have also been completed. The Bangladesh Acute Nerve Damage Study (BANDS) followed a cohort of over 2500 new patients for 5 years, to describe the history of nerve damage in leprosy and response to treatment (8). The TRIPOD (Trials in Prevention of Disability) studies researched the potential of prophylactic steroid to prevent new nerve damage (9), and to treat both very early (10) and longstanding (>6 months) nerve damage (11).

This paper seeks to collate some of the available data and research on disability related to leprosy, and to examine recent developments in work by NGOs, in particular The Leprosy Mission International, with leprosy affected people living with disabilities in Bangladesh.

DATA COLLECTION

Data on leprosy control progress is routinely collected and returned to the National Leprosy Elimination Programme (NLEP) headquarters in Dhaka for examination quarterly. Data is segregated by sex, and treatment classification. Incidence of WHO 'Disability' Grade 2 status among new cases, equating to a visible impairment due to leprosy, or a significant sight-affecting impairment of the eyes resulting in vision less than 6/60 in either eye, is routinely monitored. Population data is derived from national census data, most recently updated in 2001.

Eight NGOs are involved in leprosy control in Bangladesh. Many are implementing tuberculosis control programmes alongside leprosy work, and work within public health centres in close collaboration with government health colleagues. The longest and largest single project collaborating with the NLEP in systematic leprosy control activities is the Danish Bangladesh Leprosy Mission (DBLM), a project of The Leprosy Mission (TLM) in north-west Bangladesh, close to Nepal. Case detection and trends from DBLM were reported in 1996 (12), and much of the research work has been undertaken and new strategies in the field of leprosy-related disability in Bangladesh trialled in this project. The published Annual Reports of DBLM and other TLM projects in Bangladesh have been used as sources of data presented here.

OVERALL TRENDS IN INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE OF LEPROSY

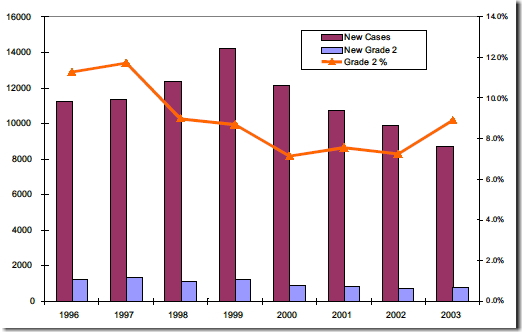

The number of new leprosy cases in Bangladesh with visible physical impairment at diagnosis (characterised by the World Health Organisation as Grade 2 'disability'), has gradually declined in the last decade as shown in Figure 1. Nevertheless, the percentage of those with such impairments still stands above 5% at diagnosis (the unofficial target of many countries), and increased in 2003 despite active community awareness programmes in many areas where NGOs are working. Impairment rates at diagnosis are higher in multibacilliary (MB) patients, who have lower immunity to "Mycobacterium leprae" and more advanced disease, and in men.

Figure 1. Bangladesh total new leprosy cases and those with visible (WHO Grade 2) impairment at diagnosis by year

In comparison with India, Bangladesh has a relatively high rate of visible physical impairments due to leprosy at diagnosis, despite or perhaps because of the very active approach to leprosy and high quality data recording of NGOs. Many NGOs have documented much higher rates than government services over long periods of time, both within Bangladesh and elsewhere.

Failure to detect or record leprosy-related nerve function impairment in overworked primary health care services, is the most likely explanation for these discrepancies. There are, in addition, large numbers of new cases of leprosy who might be expected to have nerve function impairment at diagnosis, on the basis of the BANDS data on people with neuritis, many of whom had a 'silent' nerve function loss, of which they were unaware, but which was detectable on specific sensory or muscle testing.

These observations call into question lower rates reported elsewhere in Bangladesh, and its neighbouring countries, especially in integrated programmes where staff have little training, time or inclination to test for and record physical impairments in new cases of leprosy. Data from north Bangladesh and elsewhere, have demonstrated a clear relationship between delay to diagnosis with onset of MDT treatment, and the development of physical impairments due to leprosy (13). One study (14), reported most of the delay being due to a 'wait-and-see' approach by the affected person, though a significant number of intermediate treatments were attempted before definitive diagnosis and treatment for leprosy, highlighting the need for enhanced community and health provider awareness.

NEW PHYSICAL IMPAIRMENTS

Many more affected persons develop physical impairments over time. In five years of follow- up of the BANDS cohort from the DBLM project in north Bangladesh, the incidence rate of new Nerve Function Impairment (NFI) amongst MB affected persons was 16.1 per 100 person years at risk (PYAR), with 121/357 (34%) developing NFI during the observation period (7). Of the 121 with a first event of NFI, 77 (64%) had this within a year after registration, 35 (29%) in the second year, and the remaining 9 (7%) after 2 years. The incidence rate of first event of NFI amongst Paucibacilliary (PB) cases, was much lower with only 2.5% developing NFI during the observation period. A simple prediction rule developed based on these observations and published in 2000 (15), assigned new leprosy cases to one of three risk groups(mild, moderate and high risk) on the basis of leprosy treatment group (PB/MB) and the presence or absence of any nerve function loss at registration. Persons with PB leprosy and no nerve function loss had a 1.3% (95% CI 0.8- 1.8%) risk of developing NFI within 2 years of registration; persons with PB leprosy and NF loss present, or MB cases with no NF loss present, had a 16% (12-20%) risk; and patients with MB leprosy and NF loss present at registration had a 65% (56-73%) risk of developing new NFI within 2 years of registration.

Treatment of nerve function impairment, detected within 6 months of occurrence, typically includes a moderate dose (1mg/kg/day) of oral corticosteroids for three to four months. Croft et al have shown the practicality of this in field programmes, largely run by para- medical staff (16). Implementation of field treatment of neuritis is, however, probably only available in a small number of centres world-wide, limiting its access for people on treatment for leprosy. In Bangladesh, many medical officers have little experience of leprosy and are reluctant to prescribe steroids in the event of leprosy reactions or where nerve function loss is occurring, let alone authorise trained field paramedical workers to detect such nerve damage, prescribe steroids urgently, and follow-up treatment. Nevertheless, the TRIPOD study clearly documents the safety of such an approach under field conditions in rural Bangladesh and Nepal. This information needs to be more widely disseminated and discussed, in order to minimise future disability in people affected by leprosy.

Recent studies have demonstrated significant rates of self-healing of neuritis, and long- term follow up of the BANDS cohort has not clearly shown a benefit of standard steroid therapy (8), indicating the need for further research into optimal treatment of leprosy- related neuritis. The TRIPOD 1 study (9) attempted to prevent new nerve function impairment in 600 affected persons in Bangladesh and Nepal, with new MB leprosy through administration of 4 months of low dose prednisolone. At 4 and 6 months a clear protective benefit in the treated group was evident, however, by 12 months this effect was no longer statistically significant, and was not considered sufficient by investigators to warrant the recommendation of routine preventative treatment with steroids. The TRIPOD 2 study used highly sensitive tests to detect and treat very early sensory ulnar and posterior tibial nerve damage due to leprosy, using Semmes Weinstein graded monofilaments at selected standard sites on the feet and hands. No advantage was shown over routine field testing with ball-point pen in terms of neurological outcome (10), when testing is done appropriately under field conditions. The TRIPOD 3 study showed no evidence for the use of steroid in persons with nerve function impairment detected more than 6 months after onset (11), which highlights the need for early diagnosis of leprosy and early detection of new impairments.

ACTIVITY AND PARTICIPATION

There are few data regarding limitation in activity and participation for leprosy affected people, in Bangladesh. Activity limitation scales are not used in any leprosy project of Bangladesh, to the author's knowledge. Croft et al have documented a dramatic change in knowledge, attitude and behaviour of the general community towards leprosy and leprosy affected people in an area heavily saturated with community level health promotion activities regarding leprosy (17). In a one year cohort of 2364 new cases in north Bangladesh, over 15% had detectable physical nerve damage due to leprosy, and 2.1% reported specific social problems and stigmatisation due to the disease within a month of initial diagnosis. Such problems in participation were significantly higher for women than men (4.2% vs 1.1%) (18). Anecdotally, paramedical workers report a dramatic decrease in stigmatisation from two decades earlier, where affected persons (and sometimes leprosy programme staff) were routinely refused entrance to local shops, workplaces, buses, and banks, and were forced to live apart from their relatives and neighbours. Such occurrences have now become rare, though relevant legislation restricting travel and public participation remains unrepealed.

In recent years, TLM has attempted to facilitate the mobilisation of leprosy-affected people into groups for self-help and development purposes. To date, over 200 groups of 5-15 people over a wide area have formed with the objectives of mutual support in keeping healthy and mobile, developing joint savings and credit facilities, increasing self-confidence and self-reliance, and forming a common platform for advocacy. Many of these groups are from rural communities and are a relatively homogenous group of people with physical impairments due to leprosy. Some have joined with people living with other disabilities. In other locations, especially in Dhaka, the groups are more heterogenous still, incorporating people, usually women, both with and without disabilities. They are often more concerned with addressing common issues of poverty and general ill-health than disability per se. As yet, the coalescing of these groups into wider networks is in a formative stage, though specific capacity-building efforts with this in view have been planned in discussion with these groups and communities. There is also no formal link between these groups and other groups or organisations working with persons with disability in Bangladesh, nor with the international advocacy and development umbrella organisation of people affected by leprosy.

CONCLUSION

In Bangladesh, as elsewhere in South Asia and the world, only in the last few years has any kind of decline in new case detection been documented, and this is not true in all centres. Some have expressed concern that declines may be artefactual (19) and related to less emphasis on leprosy following 'elimination', which has largely been achieved through greatly improved case management and shortened treatment regimens. If many leprosy cases remain hidden, this is more so for leprosy-related disability. Most national programmes, including Bangladesh, do not routinely test persons on treatment for new nerve function impairment, or do so only quarterly, and the data is often not recorded, nor collated centrally. It is reasonable to assume that most persons developing nerve function impairment while on treatment are undetected and untreated, though data suggests that a considerable proportion will self-heal, at least to some degree.

The paucity of data on limitations in participation of people affected by leprosy, is regrettable. Attempts to develop standardised scales to measure activity and participation limitations are underway (20), but are not widely known or used by programmes treating leprosy. Moreover, they are likely to require significant training and financial commitment to implement. The emergence of national and international networks of people affected by leprosy is encouraging. In Bangladesh, despite the large numbers of people affected, this movement is still in its infancy, though a large constituency is developing, and through networking will hopefully coalesce into a strong movement for advocacy and change. The scarcity of interaction between these groups and other groups of disabled people, and organisations working in the field of disability limits the transfer of benefits gained for and by people living with disabilities to people affected by leprosy. In future, it is to be hoped that stronger alliances can be formed with others in the health, disability, and development sectors, to ensure the mainstreaming of leprosy, to accelerate its de- stigmatisation, and to enhance quality of life for the many people affected by it in Bangladesh and beyond.

*1 C/o. The Leprosy Mission New Zealand

PO Box 10227, Balmoral

Auckland, New Zealand.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Special appreciation is given to the Bangladesh National Leprosy Elimination Programme and to the Leprosy Mission and its staff, for their provision of necessary data.

REFERENCES

- Job CK. Nerve damage in leprosy. Int J Lepr., 1989; 57: 532-539.

- van Brakel W H. Peripheral neuropathy in leprosy and its consequences. Lepr. Rev., 2000;71 Suppl S146-153.

- Lockwood DN. Leprosy Elimination - a virtual phenomenon or a reality? BMJ 2002; 324:1516- 1518.

- Meima A, Richardus JH, Habbema JDF. Trends in Leprosy Case Detection Worldwide since 1985, Lepr. Rev., 75:19-33.

- Jiang J, Watson JM, Zhang GC, Wei XY. A field trial of detection and treatment of NFI in leprosy: report from national POD pilot project. Lepr. Rev., 1998; 69:367-75.

- Croft RP, Richardus JH, Smith WCS. Field treatment of acute NFI in leprosy using a standardized corticosteroid regimen: first year's experience with 100 patients. Lepr. Rev., 1997; 68:316-25.

- Withington, SG et al. Current Status of Leprosy and Leprosy Control in Bangladesh: an ongoing collaboration. Submitted to Leprosy Review for publication.

- Croft RP, Nicholls PG, Richardus JH, Smith WCS. Nerve function impairment in leprosy: design, methodology and intake status of a prospective cohort study of 2664 new leprosy cases in Bangladesh. Lepr. Rev., 1999; 70: 140-159.

- Smith, WCS, Anderson AM, Withington SG, van Brakel WH, Croft RP, Nicholls PG, and Richardus JH. Steroid prophylaxis for prevention of nerve function impairment in leprosy: randomised placebo controlled trial (TRIPOD 1), BMJ, Jun 2004; 328: 1459.

- van Brakel WH, Andersen AM, Withington SG, Croft RP, Nicholls PG, Richardus JH, Smith WCS. The prognostic importance of detecting mild sensory impairment in leprosy: a randomized controlled trial (TRIPOD-2). Lepr. Rev. (2003) 74 p300-310.

- Richardus JH, Withington SG, Andersen AM, Croft RP, Nicholls PG, van Brakel WH, Smith WCS. Treatment with corticosteroids of longstanding nerve function impairment in leprosy: a randomized controlled trial (TRIPOD-3). Lepr. Rev. (2003) 74 p311-318.

- Richardus, J. H., Meima, A., Croft, R. P., Habbema, J. D. Case detection, gender and disability in leprosy in Bangladesh: a trend analysis, Lepr. Rev. 70(2), 1999, pp160-73.

- Nicholls PG, Croft RP, Richardus JH, Withington SG, Smith WCS. Delay in presentation, an indicator for nerve function status at registration and for treatment outcome-the experience of the Bangladesh Acute Nerve Damage Study cohort. Lepr. Rev . (2003) 74 p349-356.

- Nicholls PG, Nav Chhina, Bro Aaen K, Barkataki P, Kumar R, Withington SG, and Smith WCS. Factors contributing to delay in diagnosis and start of treatment in leprosy - analysis of help- seeking narratives in northern Bangladesh and in West Bengal, India. Lepr. Rev. (2005) March.

- Richardus JH, Nicholls PG, Croft RP, Withington SG, Smith WCS. Incidence of acute nerve function impairment and reactions in leprosy: a prospective cohort analysis after 5 years of follow-up. International Journal of Epidemiology 2004;33:337-343.

- Croft RP, Nicholls PG, Steyerberg EW, Richardus JH, Smith WCS. A clinical prediction rule for nerve function impairment in leprosy patients. Lancet, 2000; 355:1603-1606.

- Croft RA, Croft RP. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding leprosy and tuberculosis in Bangladesh. Lepr Rev., 1999; 70: 34-42.

- Withington SG, Joha S, Baird D, Brink M, Brink J. Assessing socio-economic factors in relation to stigmatisation, impairment status, and selection for socio-economic rehabilitation: a 1-year cohort of new leprosy cases in north Bangladesh. Lepr. Rev. (2003) 74, 120-132.

- Lockwood DNJ. Leprosy Elimination: A virtual phenomenon or a reality? BMJ, 324: 1516-8.

- van Brakel, Wim H. Measuring leprosy stigma-a preliminary review of the leprosy literature. Int J Lepr, Sep 2003.