BRIEF REPORTS

BEYOND COMMUNITY BASED REHABILITATION: CONSCIOUSNESS AND MEANING

Tavee Cheausuwantavee*

ABSTRACT

This article seeks to explore CBR through different perspectives. Based on existing literature and research on CBR, the paradoxes between CBR as ideal and CBR in usual practice, are identified. The dual meaning of 'disability' through 'stigma' and 'empowerment' perspectives is explored, along with the dual understanding of 'community consciousness' as 'individualism' and 'collectivism'. The two dimensions of 'disability' and 'consciousness' together are characterised into four distinct paradigms. Most past rehabilitation services are placed in a stigma-collective paradigm. It implies that philanthropy, inter-subjective value, morality and public awareness of society have usually constructed and supported any help and services for people with disabilities, including CBR. This paper looks at limitations of the past perspectives on CBR, and also points out the need for 'consciousness' studies on CBR. To understand the discrepancies of CBR, people need to look "beyond" CBR as it is commonly understood.

INTRODUCTION

Since its inception about three decades ago, community based rehabilitation (CBR) has evolved as a social model approach (1) for enhancing quality of life for persons with disabilities (PWDs), particularly for those in developing countries. The evolution of CBR has spanned over three decades, the first during 1980-1989, the second during 1990-1999, and the third beginning in 2001 (2).

Based on a social model, the tenets of CBR have been defined by various authors (1,2,3).

- CBR focuses on empowerment, rights, equal opportunities and social inclusion of all PWDs.

- CBR is about collectivism and inclusive communities where PWDs, their families and community members participate fully for resource mobilisation and development of intervention plans and services for PWDs.

- CBR needs to be initiated and managed by insiders in the community, rather than outsiders, for its sustainability.

There have been many studies on CBR, particularly from the majority world (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). Most studies point out that ideally, CBR could have provided developing countries with an approach to effectively reach all their disabled citizens. However, CBR as it developed has illustrated both positive and negative aspects and has also become somewhat controversial. Most of the studies have limited themselves to quantitative study or positivism (18), emphasising empirical study and objective reality. Studies of CBR have looked at dimensions such as attitudinal survey, quantitative assessment and evaluation, descriptions of CBR, explanations of concept of CBR and inferences from secondary data. Therefore, in the past CBR tended to be treated as a static variable or objective reality, focusing on the medical model or social model, rather than viewing it through the perspective of dynamic and pluralistic realities which naturally exist in the world.

CONTRIBUTIONS AND PROBLEMS OF CBR

Many studies have pointed out the positive and powerful aspects of CBR (4,5,6,11,12,16, 19). They have recorded contributions of CBR as a strategy for promoting positive attitudes of society toward PWDs, and in improving coverage of services for PWDs who otherwise would not have access to institution based services because of cost constraints, transportation problems, limited availability of professionals or services. These studies have stressed that CBR is a valid and crucial strategy for enhancing quality of lives of all PWDs in the community.

However, a large number of studies have also identified negative and paradoxical aspects of CBR (7,10,16,19,20,21). For instance, financial support for CBR projects has been inadequate, and available mainly from external donors, particularly international nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and other charity based organisations (16,20,22). Thus, CBR projects have found it difficult to sustain their activities on withdrawal of external donors and funding. In addition, due to poverty and the influence of capitalism, CBR workers have become stakeholders who need salaries and benefits (23, 24) rather than volunteers and collectivists who could devote themselves to their work without wages or any benefits. While promoting positive attitudes toward PWDs has been one of the contributions of CBR, much of the community have continued with negative attitudes toward PWDs as incapable, sinful, or as people paying for sins of previous births (25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30). As a result, PWDs tend to be discriminated against, stigmatised and labelled, without empowerment, equal opportunities or social inclusion. Some communities believe that it is difficult and even impossible to provide rehabilitation services for PWDs, while others believe that rehabilitation services must be managed by families or professionals (16, 31, 32). Many early CBR projects have adopted a top-down approach and are run by outsiders without adequate attention towards community concerns and participation. These problems and their complexities are a major challenge for the further development and progression of CBR.

Literature has thus identified three discrepancies or paradoxes between CBR as ideal and CBR in usual practice. First, although CBR is supposed to focus on empowerment, rights, equal opportunities and social inclusion of all PWDs, in practice much of the community have negative attitudes towards PWDs. Second, CBR is about collectivism and inclusive communities, while in practice CBR workers are stakeholders and individualists who need wages and benefits. Third, CBR is supposed to be managed by the community, while in practice, CBR projects often are top-down in approach and run by outsiders without consideration towards community concerns and participation.

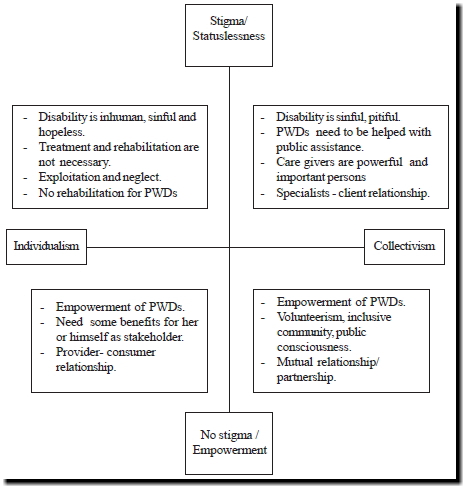

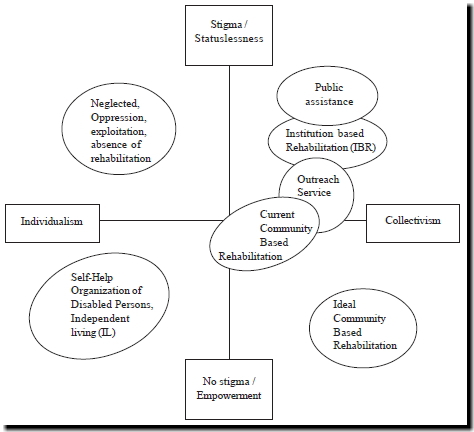

If one looks at the dual meaning of disability in terms of stigma and empowerment, and the dual community consciousness in terms of individualism and collectivism, and if one takes the two dimensions of meaning of disability and consciousness together, one can arrive at four distinct paradigms. These are stigma-individualism, stigma - collectivism, empowerment - individualism and empowerment - collectivism (Figure 1). Traditional rehabilitation services, public assistance, institution based rehabilitation (IBR), outreach, CBR, self- help services or independent living (IL) movement can be placed within each paradigm (Figure 2). Although some services may not be strictly separate from each other, most of the past services for PWDs can be placed in the stigma-collective paradigm. It implies that philanthropic basis, inter-subjective value, morality and public awareness of society usually have supported help and services for PWDs, including CBR.

This underscores the fact that CBR as a social model as understood today, may be only an ideal. Alternative conceptualisation of CBR as a socio-medical model, along with other models should be recognised and accepted for more appropriate provision.

Figure 1. Concepts and experiences reflected by meaning of disability and community consciousness

Figure 2. Services for PWDS placed by meaning of disability and community consciousness

TOWARD CONSCIOUSNESS AND MEANING OF CBR

To understand the discrepancies and interplays of CBR in terms of its holistic, dynamic nature in a meaningful manner, alternative inquiries besides traditional positivism or quantitative inquiry need to be undertaken. In recent years, there are a few qualitative studies and discussions on the importance of qualitative research (33, 34, 35, 36). Qualitative research methods are usually employed in fields such as anthropology, ethnography, grounded study, critical study, hermeneutic study, discourse analysis and so on. Qualitative research also needs to be understood in terms of its philosophical background and paradigm including ontology, epistemology, theory, methodology and data source (37, 38). In response to viewing CBR through a collective perspective, research methodology also needs to be constructed appropriately, to look at issues such as motivation, feeling, awareness and intentionality of individuals involved in CBR. Consciousness study (39, 40) is likely to be appropriate for this purpose.

Phenomenology is one of methods of qualitative research, the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, its being directed toward something, as it is an experience of or about, some object. An experience is directed toward an object by virtue of its content or meaning (which represents the object) together with appropriate enabling conditions. Thus, it tends to oppose positivism or objectivism. Phenomenology can be one of crucial disciplines to develop methodologies to address and understand the holistic and dynamic nature of CBR. It can also contribute towards transformative learning (41) for PWDs and their families, community members, professionals and researchers involved in CBR.

CONCLUSION

From the inception of CBR about three decades ago as a valid and worthwhile strategy for enhancing quality of life for all PWDs, it has been implemented in many countries, particularly developing countries. Many studies have reported problems of CBR in practice. The discrepancies between the tenets of CBR as an ideal and in practice, can be illustrated and studied with critical disciplines rather than positivism ones. These issues are "beyond" the traditional perspectives and inquiry. CBR can be viewed as the phenomenon of human consciousness and intentionality. The study of consciousness and human collective from a phenomenology perspective can be undertaken for better understanding of CBR. Although phenomenology has its own limitations, it can be an alternate perspective to help focus on the ways in which individuals construct in their own consciousness, the meaning of disability and CBR.

*Ph.D. Candidate

Faculty of Social Administration

Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand

e-mail: tavee98@yahoo.com

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study is part of a doctoral dissertation of the author. The author acknowledges with thanks the principal advisers, Associate Professors Dr. Kitipat Nontapattamadul, Dr. Jitprapa Sri-on, and other committee members, Associate Professor Kitiya Naramat, Dr. Tithiporn Siriphant-Puntasen and Dr.Preecha Peiumpongsan who provided their strong academic support to this work. The author is particularly thankful to the key informants and participants in CBR projects at Phuthamonthon District, Nakornpratom Province.

REFERENCES

- ILO,UNESCO, WHO. Community based rehabilitation for and with people with disabilities. Joint position paper. Geneva, 2004.

- Thomas M, Thomas M J. Manual for CBR planners. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2003: 1-88.

- Peat M.The changing ideology of community based rehabilitation. Saudi Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation 1999; (Jan-Mar): 32-37.

- Sasad A. Expectation in community based rehabilitation of physically disabled persons: case study Bandung District ,Udonthani Province. Unpublished master degree thesis in population education, Graduate School, Mahidol University.Thailand, 1998.

- Sangsorn R. Study of child rehabilitation in community: case study of the child rehabilitation project in Boauyai district, Nakornratchasrima province. Unpublished master degree thesis of social work, Graduate school, Thammasat University, Thailand, 1998.

- Tawornkit K. Study of knowledge performance regarding CBR and attitudes toward disabled persons of personnel who worked in public social welfare sector. Unpublished master degree thesis of social work, Graduate school, Thammasat University, Thailand, 1995.

- Rehman F. Woman, secluded culture and community based rehabilitation: an example from Pakistan. Saudi Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation 1999; (Jan-Mar): 16-20.

- Boyce W, Kadonaga D. Family roles of disabled women in Indonesia. Saudi Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation 1999; (Jan-Mar): 25-31.

- Price J P, Marquis R. CBR has a thousand faces. Saudi Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation 1999; (Jan-Mar): 38-42.

- Tjandrakusuma H. Towards the 21 st Century : Challenges for community based rehabilitation in Asia and the Pacific region. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 1998; 9(1): 51-58.

- Tunga W N. Rural community based rehabilitation (The Indian experience). Saudi Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation 1999; 5(1): 57-59.

- Zhuo D. Recent trends of community based rehabilitation in China. Saudi Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation 1999; 5(1): 61-63.

- Deepak S, Sharma M. An inter-country study of expectations, roles, attitudes and behaviours of community based rehabilitation volunteers. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2003; 14(2): 179-190.

- Raj J, Latha P, Metida. Needs assessment of programmes integrating community based rehabilitation into health activities. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2004; 15(1): 69-74.

- Sharma M. Using focus groups in community based rehabilitation. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2005; 16(1) :41-50.

- Cheausuwantavee T. Community based rehabilitation in Thailand: current situation and development. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2005; 15(2) :50-66.

- Bury T. Primary health care and community based rehabilitation: Implications for physical therapy. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2005; 16(2) :29-61.

- O'Brien M, Penna S. Theorising welfare: Enlightenment and modern Society. London : SAGE Publications, 1998.

- Office of promotion and protection for persons with disabilities. Evaluation reports of community based rehabilitation programme of 5 provinces. Thailand: Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, 2005.

- Thomas M, Thomas JM. A discussion on the relevance of research in the evolution of community based rehabilitation concepts in South Asia. Saudi Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation 1999; 5(1): 21-24.

- Kendall E, Buy N, Larner J. Community based rehabilitation service delivery in rehabilitation: the promises and the paradox. Disability and Rehabilitation 2000; 22.

- World Health Organization. Community based rehabilitation and the health care referral services: a guide for programme managers. Geneva, Switzerland, 1995.

- Brinkman G. Unpaid CBR work force: between incentives and exploration. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2005; 15(1) :90-94.

- Thomas M, Thomas MJ. A discussion on controversies in community based rehabilitation. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2002; 13(1).

- Goffman E. Stigma : note on the management of spoiled identity. USA,N.J: Prentice- Hall, Inc,1963.

- Devlinger P. Why disabled? The cultural understanding of physical disability in an African Society. In Ingstad B, Whyte RS(ed). Disability and culture. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, London ,1995: 94- 106.

- Nicolaisen I. Person and nonpersons: disability and personhood among the Punan Bah of Central Borneo. In Ingstad B , Whyte RS(ed). Disability and culture. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, London ,1995: 38-39.

- Sentumbwe N. Sighted lovers and blind husbands: experiences of blind woman in Uganda. In Ingstad B ,Whyte RS (ed) . Disability and culture. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, London,1995: 159-173.

- Cheausuwantavee T. Sexual problems and attitudes toward sexuality of persons with and without disability. The journal of Sexuality and Disability 2002; 20( 2) : 125- 134.

- Bury T. Primary health care and community based rehabilitation: implications for physical therapy. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2005; 16(2):33.

- Coleridge P. Disability, liberation and development. Oxford, UK: Oxfam,1993 in Bury T. Primary health care and community based rehabilitation : implications for physical therapy. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2005; 16(2):33.

- Lysack C, Kaufert J. Comparing the origins and ideologies of the independent living movement and community based rehabilitation. Int J Rehabil Res 1994; 17: 231-240 in Bury T. Primary health care and community based rehabilitation : implications for physical therapy. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2005; 16(2):59.

- Lysack CL. (Re) Questing community: a critical analysis of community in the discourse of community rights and community based-rehabilitation. Digital dissertation: UMI Proquest, University of Minitoba , Canada, 1997.

- Ballantyne SM. Community based- rehabilitation under conditions of political violence : a Palestinian case study. Digital dissertation: UMI Proquest, University of Minitoba , Canada, 1999.

- Muhit M, Hartley S. Using qualitative research methods for disability research in majority world countries. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2003; 14(2):103-114.

- Turmusani M. An eclectic approach to disability research: a majority world perspective. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal 2004; 15(1):3-11.

- Rubin A, Babbie E. Research Methods for Social Work (3 rd edition). USA: Brooks /Cole Publishing Company,1997.

- Zimmermann W. Introduction to theory. Power point presentation for doctoral students of Social Administration faculty, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2004.

- Capra, F. The Tao of Physics. In Cazenave, M. Science and Consciousness: Two views of universe. UK: Pergamon Press, 1984.

- Wilber, K. An integral theory of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 1997; 4(1) : 71-92.

- Mezirow J, et al. Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: a guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. USA: Jossey- Bass Inc Publishers, 1990.