Disabled Village Children

A guide for community health workers,

rehabilitation workers, and families

PART 2

WORKING WITH THE COMMUNITY:

Village Involvement in the Rehabilitation, social integration,

and Rights of Disabled Children

CHAPTER 53

Education

At Home, At School, At Work

Guided learning to help a child gain skills and understanding for meeting life's needs is called 'education'. In Chapters 34 to 43 we talked about ways to help disabled and delayed children learn to control and use their bodies and minds, and to master early basic skills for daily living. But as a child grows up many additional skills and knowledge are needed.

For nearly all children, education begins in the home. For some it continues in school; for others in the fields, in the forest, at the marketplace, on the riverbank, or in the streets.

In the cities of most countries, a school education has become almost a 'basic need' for getting a job or being accepted by society. In many villages and farming communities, however, 'book learning' still is much less important than the skills children learn through helping their families with daily work.

In some rural areas, therefore, it may be a mistake to think that 'every child' should go to school. For the child who is physically strong but mentally retarded, schooling may be a frustrating and unrewarding experience, especially if no 'special education' is available. The child may be happier and learn more skills for meeting life's needs by helping father in the fields, or mother in the marketplace, than by going to school.

However, for some retarded children in rural areas, schooling can be important. If the teacher and other children can be helped to understand the special needs of the child, treat him with respect, and give him encouragement, the slow learner may benefit greatly from school, both educationally and socially.

Whatever the case, it is important to consider the local situation carefully. Do not just follow the recommendations from the outside about the importance of schooling. Some school situations are better and some are worse than others. So before deciding for a particular child, look carefully at the good and the bad things about the local school and consider the other choices.*

For the physically disabled child in the rural area, schooling may be especially important- more so perhaps, than for able-bodied children. Physically disabled children often cannot do hard physical farm work as well as the able-bodied. Therefore, they need to learn skills using their minds, so that they can work or take part in community activities. It may help them to go as far in school as possible.

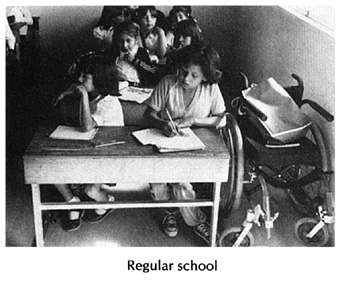

Regular school or special schools?

Today, leaders in rehabilitation generally feel that disabled children should attend the same schools as other children, whenever possible.

For mildly or moderately disabled children this should not be a big problem. if the parents, school director, and teachers cooperate. In some communities, however, and especially in rural areas, parents may not even think of sending their disabled child to school. They may fear that their child will be teased or have too hard a time. And in some places, school directors or teachers refuse to accept even a moderately disabled child with a quick mind. Distance and other problems getting to school also add to the difficulties.

Wherever possible, try to overcome these problems. Village rehabilitation workers can talk to teachers, parents and other schoolchildren and try to work out the best situation. At times parents may need to organize and put pressure on the schools to change their policies. In some countries, laws exist requiring government schools to accept and make special provisions for disabled children. Rehabilitation workers and parents can find out about the laws, and try to have them enforced. Or they can work to get laws passed if they do not exist.

Every effort should be made to make regular schooling easier and more enjoyable for the disabled child. Some possibilities that involve other schoolchildren have already been discussed in Chapter 47 (CHILD-to-child).

*Even non-disabled children are in some ways often damaged by school, even as in other ways they are helped. For an excellent critical analysis of public school in the social context, see Letter to a Teacher by the schoolboys of Barbiana. These rural Italian boys declare that "School is a war against the poor." (See Page 641.)

For more severely disabled children, attending regular schools often may not be possible, at least as schools exist today. Yet, sometimes if you talk with the teachers and other children, they will become more understanding and make special arrangements.

For example, we know a boy with spina bifida who lacks bowel control and therefore never went to school. But after his parents talked with the teacher and schoolchildren, an agreement was reached. Now the boy goes to school. When he has an accident in his pants, he quietly gets up and goes home to bathe and change. (Fortunately his house is very near the school.)

In cases where some disabled children cannot attend regular school, other alternatives may be possible. In cities of some countries there are 'special education 'programs for children with certain disabilities. Such schools, if private, are usually very expensive and if public, are often overcrowded or have long waiting lists.

In the rural areas, with rare exceptions, there are no special education programs. However, parents of disabled children may be able to organize and form their own ' special school'. The group helps each child to learn at her own pace and in her own way. An example of such a school is'Los Pargos' in Mazatlan, Mexico, described briefly on Page 517. Also, the Centre for Community Rehabilitation Development in Pakistan has helped organize parent-run special education programs in many towns (see Page 520).

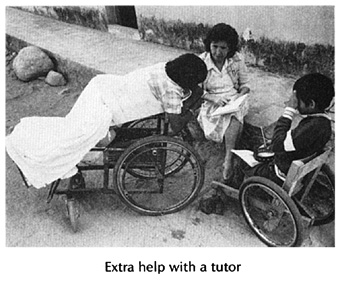

If no opportunity for regular or special schooling can be worked out-or even if it can- perhaps some arrangement can be made for study at home. Children who do go to school, either non-disabled or disabled, may be able to help teach the severely disabled children at home after school. A community rehabilitation program can also include a study program for disabled children and youths. Project PROJIMO has arranged at the local village school for attendance of children with special needs who have had difficulty in schools elsewhere. In addition, the disabled rehabilitation workers assist the children who need special tutoring in the evenings.

|

|

|

This book does not cover the details and methods of special education. It is important that the methods used be adapted to the local customs and situation- not just borrowed from Europe or the USA, as is often done. An excellent book on Special Education For Mentally Handicapped Pupils, by Christine Miles has been developed for the program in Pakistan, and has many ideas for adapting to the local culture. (See Page 640.)

Meeting the special physical needs of children at school

When physically disabled children are in school or studying, it is important to remember their special needs, and try to meet them.

For example, children who cannot get up and run around should usually not spend all day sitting in a wheelchair. This tends to lead to contractures, swollen feet, weak leg bones, spinal curve, and other deformities.

So try to arrange for the children to spend at least part of the day with their bodies in a straight position.

Part of the day this can be done in standing frames (but usually not for more than half an hour at a time).

And part of the time it can be done lying down, either on the floor, or on 'wedges' or mats that permit better positioning and use of the hands and arms.

For design details, see Pages 571 to 575.

AIDS FOR READING, WRITING, AND DRAWING

PENCIL HOLDER FOR A WEAK OR PARALYZED HAND

For children who have difficulty holding a pen, pencil, or brush, or turning the pages of a book, you can think of all sorts of adaptations. Here are a few examples:

|

|

|

|

AIDS FOR HOLDING PENCILS, PENS OR BRUSHES

A thick handhold gives better grip and control.

|

|

|

|

|

For other ideas, see Pages 223 and 330.

PAGE TURNER (Design for head)

|

|

|

|

Many children who have poor hand control and cannot write clearly by hand can learn to write well on a typewriter - using their hands or a stick attached to their heads. A typewriter may be a wise investment for an intelligent but severely disabled child -and may in time provide a way for her to earn money.

A pocket calculator is much cheaper than a typewriter. A disabled person who is good with numbers can do many different kinds of accounting jobs.

For more ideas on special aids and adaptations, see Chapter 27 on amputations, Chapter 9 on cerebral palsy, and Chapter 62 on special aids

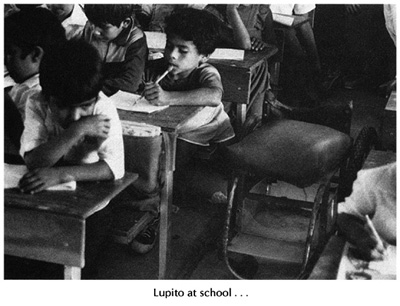

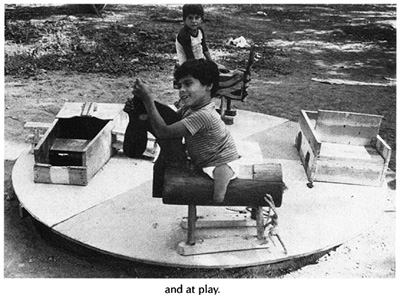

Lupito's family was afraid to let him go to school. They thought the other children would tease him. Village rehabilitation workers convinced his family to let him go to school, and to also lead a CHILD-to-child activity with the schoolchildren. Lupito now attends school happily and does very well.

Disabled Village Children

A guide for community health workers,

rehabilitation workers, and families

by David Werner

Published by

The Hesperian Foundation

P.O. Box 11577

Berkeley, CA 94712-2577