I. Introduction

This is the latest in a series of publications from the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) concerning self-help organizations of people with disabilities. Previous publications in the series include Self-Help Organizations of Disabled Persons: Reports of Three Pilot National Workshops (United Nations publication ST/ESCAP/1159), Self-Help Organizations of Disabled Persons (ST/ESCAP/1087) and Directory on Self-Help Organizations of People with Disabilities (ST/ESCAP/1330). The series is intended to generate discussion and action supportive of the efforts of people with disabilities to have more effective self-help organizations. This kind of non-government organization (NGO) can enhance full participation and equality in mainstream society, which is the goal of the Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabled Persons, 1993-2002. The capacity of people with disabilities to undertake self-advocacy, particularly through representative organizations, is central to the fulfilment of the Decade's goal.

ESCAP organized a series of subregional workshops on the management of self-help organizations of people with disabilities: a South Asia workshop in Dhaka, December 1993; an East and Southeast Asia workshop in Bacolod City, Philippines, January 1994; and a Pacific workshop in Suva, February 1996. The workshops addressed the training needs of executives and senior administrators of self-help organizations of people with disabilities from those subregions. They were directed at enhancing participants' management skills and ability to play a more effective, cooperative role in developing national polcies and programmes on people with disabilities. Much of this publication deals with discussions, information and experiences shared by the workshop participants.

Broadly, there are two types of disability organization: service-delivery organizations, which increasingly support advocacy on behalf of people with disabilities, but are often not run by them; and self-help organizations, whose decision-making power lies with a board composed of people with disabilities, and which seek to achieve the self-representation and self-advocacy of people with disabilities in national and sub-national decision-making processes. These self-help organizations are membership organizations and mostly run on a voluntary bases.

Self-help organizations of people with disabilities are weak compared with other NGOs that have emerged during the same period, particularly those dealing with the environment or with women's and children's rights. Key reasons for this relative weakness include the marginalization of people with disabilities from mainstream development programmes, which has given them a low level of skills and poor self-esteem. In addition, as a social group, people with disabilities face limited contact and communication. This is caused not only by their poor access to transport and communication infrastructure, but also by divisions among people with different types of disabilities, and any other divisions (such as gender, caste or ethnic group) that affect the cohesiveness of society and social groups.

Among self-help organizations of people with disabilities, there is a common pattern of weaknesses in management. Remedying this pattern of weaknesses is the concern of the present publication. It has two goals: first, to outline common management issues affecting self-help organizations in Asia and the Pacific; and second, to present a range of approaches that can serve as a useful reference for strengthening self-help organizations.

This publication also contains the following, inter alia:

- useful documents and publications;

- contact details for international self-help organizations and their regional offices, and regional offices of United Nations bodies and agencies.

The publication is aimed at the following groups of people:

- Management personnel, board of directors and members of organizations of people with disabilities;

- Organizations, including government organizations and NGOs, that are in a position to support the strengthening of self-help organizations;

- People with disabilities who are not yet members of an organization of people with disabilities, but could join one;

- Community members in youth groups, women's organizations and civic societies.

II. Definitions

A. Self-help and self-help organizations

These definitions are derived from the ESCAP publication Self-Help Organizations of Disabled Person.

"Self-help" means mutual support and empathetic human relationships. It is group solidarity which enables disabled people who are experiencing similar hardship to support each other and to overcome common difficulties through the exchange of practical information, insight and knowledge gained through personal experience. That solidarity and mutual support serves as a basis for collective action to improve the existing situation of people with disabilities in society.

A "self-help organization of people with disabilities" is an organization run by self-motivated disabled people to enable disabled peers in their community to become similarly self-motivated, and self-reliant. The organization may engage in efforts to provide community-based support services through mutual support mechanisms and advocacy for disabled persons to achieve their maximum potential, and assume responsibility for their own lives. Thus, a self-help organization of people with disabilities may be characterized by self-determination and control by disabled people, self-advocacy and mutual support mechanisms, aimed at strengthening the participation of people with disabilities in community life. Unless otherwise noted, the term "self-help organization", when used alone in this publication, refers to a self-help organization of people with disabilities.

B. Leadership

"A leader...is someone who is able to develop and communicate a vision which gives meaning to the work of others. It is a task too important to be left only to those at the top of organizations. Leaders are needed at all levels and in all situations... In fact, anyone who wants to get something done with or through other people can and should learn the lessons of leadership. We are all leaders at one time or another."(1)

Leaders require vision, communication, trust and self-knowledge. Leaders should develop a vision which guides their organization and makes its members or staff more confident. Leaders need good communication skills to share the vision with members. Everyone can take part in shaping the vision. Leaders can articulate it and capture it with words, visuals or other expressions, so that it enters people's imaginations. In a self-help organization of people with disabilities, leadership does not belong to a few individuals; rather, each empowered member shares leadership.

Leaders need to establish trust through consistency and integrity. They also need self-knowledge, the knowledge of their own strengths and weaknesses. Leaders "build on their strengths and compensate for their weaknesses and they consciously look for the fit between who they are and what the organization needs."(2)

In a self-help organization, leaders should learn values that the organization espouses; develop organizational development skills to maintain a democratic and effective organization; develop gender sensitivity to avoid gender stereotypes; raise critical consciousness about socio-political and economic issues in the community and analyze its situation; learn advocacy skills; and enhance communication skills.(3)

C. Management

Managers of self-help organizations may be called executive secretary, director or some other title. Their duty is to execute decisions made by the organization's board of directors. Managers have many diffeent roles, which can be divided into three basic sets: interpersonal roles (figurehead, leader and liaison), informational roles (monitor, disseminator, spokesperson) and decisional roles (entrepreneur, disturbance handler and negotiator).Those three roles may be described as leading, administrating and fixing roles, respectively.(4)

Managers of self-help organizations need skills and knowledge to help empower organization members and influence national policies and programmes that directly or indirectly affect members' lives. These skills include not only leadership qualities, but also the specific skills required to run a non-profit organization with volunteer members and some paid staff. These include skills in raising funds and other resources, ensuring good public and community relations, advocacy, supervising personnel, training staff, budgeting, accounting, and planning, monitoring and evaluating programmes.

Running an organization is demanding, and the actions taken are not always appreciated. Managers may have to be at the front line of troubleshooting, but may not get the recognition for a job well done. Many self-help organizations lack skillful managers.

D. Democratic decision-making

Democratic decision-making means that every member of an organization is guaranteed equal participation in its decision-making processes, whether this participation is direct (voting on decisions) or indirect (electing representatives to make decisions). Democratic decision-making shares responsibilities among the entire group. The participation of members in decision-making and the resulting responsibility will likely satisfy members' needs for self-actualization and self-esteem, releasing greater effort on their part.(5)

The opposite of democratic decision-making is authoritarian decision-making, in which power resides with the leader or a small group of individuals. Self-help organizations, which take enhancing the self-actualization and participation of people with disabilities as a central goal, should always use democratic decision-making.

________________________________

- 1 Charles Handy, Understanding Organizations, fourth ed. (New York, Penguin Books, 1993) p.117.

- 2 Ibid., pp.116-117.

- 3 See case study 4: "Training new leaders at KAMPI, Philippines", by Venus M. Ilagan in this publication.

- 4 Charles Handy, opcit. p.322.

- 5 Ibid., p.100.

III. Overview of self-help organizations in the region

It is not an easy task to identify and characterize self-help organizations of people with disabilities. There is a wide range of such organizations, from small village groups to nation-wide or international-level organizations. Some are large with ample resources; some are weak in terms of financial resource but successful in empowering their members. Some vocal, visible people with disabilities may claim to represent a certain group of disabled people, but it is often difficult to determine the true constituency of the group.

To find out the profiles of self-help organizations in the region, ESCAP conducted a survey of such organizations between 1991 and 1992. Seventy organizations responded to the survey. Of these, 29 (or 41 per cent) were cross-disability organizations, which represent people with two or more types of disability. The remainder were single-disability organizations, including: 16 organizations of people with visual impairmets (23 per cent); 13 organizations of people with orthopaedic or locomotor disabilities (19 per cent); 5 organizations of people with hearing impairments (7 per cent); and 7 organizations of people with other types of disabilities, such as psychiatric disorders, intellectual disabilities, speech impairments and lung disease (10 per cent).

These numbers are not necessarily representative of self-help organizations of people with disabilities in Asia and the Pacific, as organizations from only 19 countries and territories responded to the survey questionnaire, and 32 of the organizations (47 per cent of the total) were located in South Asia. Close analysis of the results, however, reveals some trends among self-help organizations.

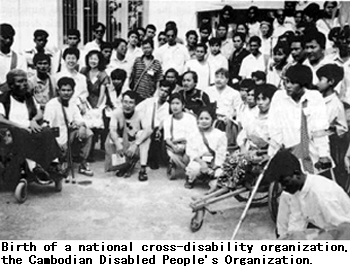

A. Cross-disability organizations

Many cross-disability organizations had a large membership, were nationally operated, and were better staffed than most single-disability organizations, excluding organizations of blind people and institution-based organizations. The average number of full-time and part-time paid staff for a cross-disability organization was 5.5 people, compared to 3 people for single-disability organizations.

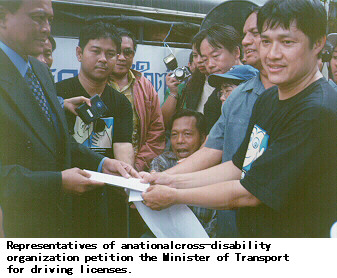

Nine cross-disability organizations were "umbrella" organizations, which attempted to represent all the people with disabilities in their respective countries. Their functions focused on advocacy, information dissemination and national coordination of their member organizations, many of which were focused on single disabilities. Their goals and objectives made their functions explicit:

- "To establish the rights of people with disabilities in society, and convince the government to protect their legal rights." (Bangladesh Welfare Organization of Disabled Persons)

-

- "To work together with the government and other relevant authorities to establish legislation and policies to protect the rights of people with disabilities in Fiji." (Fiji Disabled People's Association ).

-

- "To unite people with disabilities within the State in one constituent organization which shall act as a focus to represent them" (South Australian Branch of Disabled Peoples' International Inc.)

-

- The Council of Disabled People of Thailand had the most explicit goals:

- (a) Seek and propose legislation and regulations that will benefit all disabled people in Thailand;

- (b) Amend all legislation and regulations which discriminate against disabled people.

The Council was successful in influencing the Thai Government to enact the Rehabilitation Act of People with Disabilities in 1991 and subsequent Ministerial regulations to enforce the Act in 1994.

Many of the cross-disability organizations undertook community awareness activities, including seminars and workshops on disability and public-education campaigns, and provided training workshops for their members concerning their rights and advocacy skills. As most cross-disability organizations were federations of organizations, their major focus was on advocacy and awareness promotion activities. Some organizations offered direct services, including vocational training, job placement service and a medical supply programme, but they rarely considered this to be their primary function. Fiji Disabled People' Association stated in its mission statement: "FDPA will provide urgent, direct services on a short term basis until these services can be assumed by an appropriate public or private agency."

Cross-disability organizations also existed at the small-scale, local level. It is usually not feasible to establish organizations of persons with a single disability in a village or small town, simply because there are not enough persons with one disability. Therefore, it may be more feasible to form cross-disability groups that can serve people with all types of disability in a village. Sanghams of village disabled persons in South India (see Case-study 5) and independent living centers in Japan (see Case-study 6) are examples of such local cross-disability organizations.

B. Single-disability organizations

The single-disability organizations, which formed the majority of the organizations surveyed, said they operated at the national and provincial levels, rarely at the village level. They were formed to meet specific needs among a certain disability group, and so tended to provide more direct services to their members than cross-disability organizations did. For example, organizations of blind people usually provided through Braille libraries loan services of Braille books and tapes for their members; provided assistive devices such as white canes and braille slates; and organized Braille training and vocational training, as well as job placement services. One organization undertook community-based rehabilitation programmes for blind people in rural areas, operated day-care centres for older blind people, operated Braille equipment banks, and published Braille journals. Another organization operated a home for blind women, an eye hospital with 20 beds and a talking book library with 96 full-time and 6 part-time paid staff.

Many single-disability groups conducted advocacy work, although they focused on issues specifically related to the disabilities that concerned them. The most critical issue for blind people's organizations was the expansion of employment opportunities for their members.

Organizations of deaf people had more diverse functions. Their central focus was on the development of sign languages and on establishing sign-language interpretation services. They also conducted skill training courses and assisted their members in obtaining employment. They commonly provided peer counseling and peer support for their members and sign-language classes for the general public; often, they organized sports and recreational events for members. One such organization, Kathmandu Association of the Deaf, cited its goal as improving the conditions of deaf people through the development of sign language, provision of counselling services and employment support.

People with orthopaedic disabilities tended to come together as an informal social group, eventually forming a self-help organization. Over half of these organizations had no paid staff, managing the operation entirely with volunteers. Their major concerns were mobility and access to physical environments, so they focused their efforts on providing mobility aids (such as wheelchairs and tricycles), as well as on promoting accessible physical environments, especially public transportation services. Some organizations produced and disseminated assistive devices such as prostheses and orthoses as well as mobility aids.

Some self-help organizations were for people with other specific disabilities, including laryngectomy (which results in loss of the vocal cords), psychiatric conditions and mood-swing disorders. The support of professional personnel usually encouraged these organizations to form. Their objective was to provide support to people with these disability and their families through information exchange, counselling and other services to foster mutual support among disabled people and their famlies. In some instances, their membership was limited to those who had received services from one hospital or an institution; others had statewide membership.

C. Issues faced by self-help organizations in the region

1. Long-term financial support

The majority of the organizations indicated a need for long-term financial support to cover operational costs, including office rent, equipment and staff salaries. Organizations also said they required assistance in fund-raising skills such as project-proposal writing. They generally indicated that Governments provided limited financial and technical support to self-help organizations, and that local and international funding organizations allocated them little funds. This clearly demonstrates that a low priority has been given to developing self-help organizations in the region. To raise their profile in government funding priorities and among funding organizations would require vigorous public campaign efforts by concerned United Nations agencies, as well as by NGOs that support the self-representation of people with disabilities and by the self-help organizations themselves.

2. Communication and collaboration among single-disability organizations

Single-disability organizations in the region often face the problem of a lack of communication and collaboration. In many countries, for example, organizations of deaf people would not communicate and associate with organizations of blind people or people with locomotor disabilities. Often, the organizations compete with each other to receive funds from a Government or funding organizations. A cross-disability organization, however, can provide a national forum for various types of single-disability organizations. When this has occurred, as in Thailand and the Philippines, self-help organizations have participated effectively in formulating and implementing national policies and programmes for people with disabilities.