IV. Management Issues

Self-help organizations of people with disabilities face most of the manage ment problems common among NGOs, such as lack of funds and shortage of office staff. However, some management issues are more prominent than others, because of the situations that people with disabilities face. This section will discuss common management issues experienced and some approaches employed by self-help organizations to resolve those issues.

A. Concentration of power

1. Confusion of the roles of president and executive

A NGO's president or chairperson should be a volunteer. The president's role is to represent an organization and to chair the board of directors. The board, with the approval of the general assembly, will set the organization's policies and plans. The role of an executive secretary, director, or manager, by contrast, is to implement those policies and plans. (This may be a paid position.)

In some self-help organizations, however, one person fills the roles of both positions. This may lead to the concentration of power in thatindividual because of the absence of a check-and-balance mechanism. To avoid this problem, when an organization grows, it should make sure to create an executive position, directly accountable to the board of directors and not in charge of it.

2. One-person organizations

One person may dominate even a seemingly democratic decision-making process, usually as a result of a high level of education, social status or ability to articulate opinions. This may result in one-person control of the organization.

3. Imbalance of skills and experiences among members

People who have acquired disabilities late in life often dominate the leadership positions of self-help organizations, especially organizations of people with locomotor disabilities. This is because they usually have a higher level of education, and more work and social experience, from the period before they acquired their disabilities. People who were born with disabilities or acquired them in early childhood, by contrast, may lack education and experiences in socialization and work. These conditions may make it difficult for them to take leadership roles in self-help organizations.

4. Unmet need for training

Concentration of power in an organization may occur because many people with disabilities are not familiar with organization decision-making processes. They may not have been given any opportunity to make decisions in their own lives, let alone in their organizations. In such cases, members (especially board members) should receive opportunities to be trained in making appropriate decisions. The executive director or executive staff are responsible for arranging such training.

B. Staff

Many self-help organizations depend on the goodwill of committed members who can volunteer time and energy to helping the day-to-day operation of the organization. That operation (e.g., initiating and responding to correspondence) is difficult for self-help organizations, because of both language problems and a lack of personnel resources. When these difficulties lead to poor operation, it contributes to a perception of organizations of people with disabilities as being uncooperative and ineffective. Self-help organizations in such a situation need to improve their operation by recruiting volunteers or by raising funds to hire regular staff.

When a self-help organization grows, there is a need to develop paid positions within it. Paid staff should receive adequate salaries and other benefits on par with the staff of other NGOs working in the same community. However, members should take caution. Over-dependence on professional staff may weaken the participation of elected board members in the organization's management and decision-making processes. Elected members of self-help organizations need to remember that they are not employing full-time personnel to abrogate their own responsibilities and leadership.

C. Accountability

There are many levels of accountability in self-help organizations. All members should commit themselves to promoting their full participation and equality in society. At the next level, leaders of a self-help organization should see themselves as facilitators who are accountable to all members, including those from urban slums and rural areas.

1. Accountability for rural members

Members in rural areas have particular difficulty participating in activities and receiving information on activities of a large self-help organization. Often, the organization head office is located in the national or provincial capital or a large city, with the majority of board members belonging to an urban elite class. For their convenience, meetings tend to be organized in the city bases. This situation gives urban members little exposure to problems faced by people with disabilities in rural areas.

To improve the situation for rural members of self-help organizations, board members should do the following:

- (a) Spend some time listening to and consulting with rural people with disabilities;

-

- (b) Guarantee fair representation of rural disabled members (with adequate training in making decisions) on the decision-making body, taking care to avoid tokenism;

-

- (c) Rotate meeting sites between urban and rural areas.

2. Accountability of those who have received privileges on behalf of the organization

Only a few organization members can make overseas trips for training, seminars or meetings. Often, these are top leaders who do not share information and knowledge gained abroad with the rest of the membership. Organizations need a fair selection process for sending members abroad and a mechanism by which information and knowledge thus gained can be shared with all members. FDPA has developed guidelines for such mechanism. For more details, see Annex I: Guidelines for all FDPA personnel and volunteers who attend workshops sponsored by FDPA or outside donors.

3. Financial abuse

Self-help organizations often have poor financial management. Many self-help organizations do not keep up with the standards that donors require. As a consequence, they lose the trust of donors, and lose funding as a result. At worst, they may face outright financial abuse.

Case study 1: Preventing abuses of funds within a self-help organization Introduction

D. Fund-raising

Many self-help organizations face difficulties in generating funds to meet operational costs, including personnel costs, office rent and communication expenses. Many donors do not usually provide funds for operational costs. Thus, special fund-raising events become an important means for generating these costs.

Case study 2: Fund-raising in the Fiji Disabled Peoples Association (FDPA)

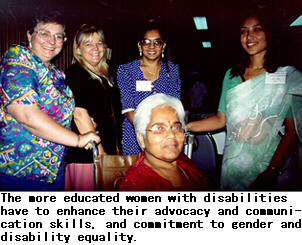

E. Gender sensitivity

Many women with disabilities are involved in the activities of self-help organizations. However, few are in decision-making or management positions. To meet the needs of women with disabilities within the organization, specific measures need to be implemented (e.g., gender sensitivity training for all leaders and members, establishment of women's committees and equal training opportunities for women with disabilities). Gender equity must be a goal t every level of an organization, not just its lower ranks.

Case study 3: The Women's Committee in the Asian Blind Union

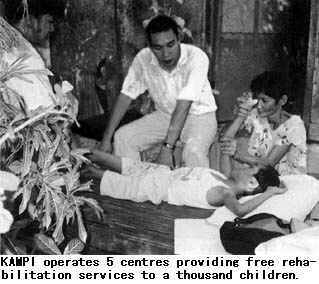

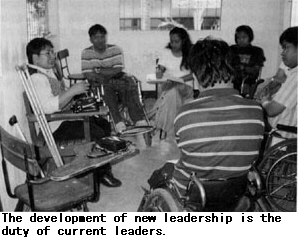

F. Organzational continuity: Development of new leaders

Many self-help organizations have not trained younger members for management and leadership positions. As a consequence, the organizations face difficulty in recruiting new members and breaking the status quo. In order to create and maintain an active organization, leaders should always look to the succession of leadership to the younger generation. The true test of a person's leadership is in what happens when he or she is no longer a leader.

Case study 4: Training new leaders at KAMPI, Philippines

Case study 1:

Preventing abuses of funds within a self-help organization(6)

Introduction

Almost every organization, even a charitable organization, will eventually be troubled by the abuse of its resources, especially financial resources. In some cases this abuse may be minor; in other cases, it can be devastating and even fatal to an organisation. The abuse may be obvious, or it may be hidden or justified through the use of such terms as "spoiled goods", "natural wastage", "commission", "staff perks", "petty cash", "miscellaneous expenses", or even "accepted practice".

Lost resources are not the only problem resulting from financial abuse. A common reaction to the discovery of financial abuse is a lack of trust from those dealing with the organization, which may include the general public. This can result in suspicion, recrimination and counter-recrimination between elected officers, staff, members and donors. This may even intrude into the personal lives of those concerned with the organization, whether connected with the abuse or not. Furthermore, volunteers and donors may become unwilling to offer further assistance and funding and membership may decline. Clearly, then, financial abuse can be a severe problem, and organizations must make every efforts to prevent, eradicate or reduce it.

Types of financial abuse

There are three main types of financial abuse. Each of these may involve cash, cheques, stamps, equipment, services or any other resources (including facilities and assets) of an organization.

The most obvious type of financial abuse is deliberate and intentional abuse, where a person or persons, inside or outside the organization, set out to convert, embezzle or otherwise transfer resources from the organization to their own personal use. This is simple theft; once detected, it is relatively easy to deal with.

The second category of abuse is management abuse, where management uses, or allows the use of, resources for purposes other than their original intention. For example, people in the organization may use funds which have been reserved for a specific project to pay for general administrative costs, or use official telephones for private calls.

The third category of financial abuse is inefficiency, where funds or resources are not used to their best advantage. For example, the organization may not consider competitive quotations for the purchase of capital equipment; it may be over-staffed; it may use premium quality paper for drafting when scrap paper is entirely suitable.

What the three categories of abuse have in common is opportunity. Deliberate abuse can only happen when its perpetrators are given the opportunity to steal. Management abuse and inefficiencies can only happen when their perpetrators are given the opportunity to spend without control, or to continue inefficiency because of a lack of control, accountability or information. The application of standard rules of conduct or procedures and systems can reduce these opportunities and thus prevent, or at least detect, financial abuse at an early date. The organization can then take appropriate action.

Three examples, taken from the same national organization, illustrate how abuses can occur.

Example 1

A national organization of people with disabilities wanted to purchase its own headquarters office. Approximately US$ 125,000 was required for the full purchase price; the organization had only US$ 16,000 in the bank, in a long-term investment account. The organization identified suitable premises, but the deposit for the building was more than the value of the organization's long-term investment. Consequently, the Executive Committee (ExCo) of the organization instructed the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) to borrow money from the organization's bankers against the long-term investment, and use the borrowed money to find a suitable short-term investment that would boost the amount available for deposit. The CEO quickly came up with a business that was looking for investors, and which promised to repay a 30 day investment with the unlikely sum of 25 per cent interest.

The organization rushed into the investment - and lost its entire savings. Confidence in the organization's management by the membership, the Government, the national disability co-ordinating agency donors and bankers hit an all-time low. The national organization, which had previously been doing well, came to within a few dollars of bankruptcy and enforced closure.

This serious problem was caused by the following abuses:

- (a) The ExCo's initial decision to instruct the CEO to seek an investment had not been ratified by the organization's full Board of elected officers. This was contrary to the organization's constitutional regulations. In addition, the decision to invest in the business was not approved by all the ExCo members, and neither was it ratified by the full Board. Once again, this was contrary to constitutional regulations. (Management abuse.)

-

- (b) In order to make the investment, the organization obtained the short-term bank loan by telling the bank that the money would be used for the building deposit. No mention was made of the 30 day business investment. To obtain the short-term loan, the organization presented the bank with the minutes of a fictitious board meeting. Those who had signed the letter to the bank (the organization's President, Treasurer and CEO) could have faced criminal charges, but the bank was happy to recover its funds from the long-term deposit which secured the short-term loan. (Deliberate and management abuse, amounting to fraud.)

-

- (c) Those who made the decision to invest did not consult professional financial advisers. The organization's bankers could have provided advice free of charge and conducted a credit rating on the business. (Inefficiency abuse.)

-

- (d) Those who made the decision to invest failed to consult professional lawyers to secure their investment. (Inefficiency abuse.)

-

- (e) The CEO, who had been appointed as a partner in the business on the instruction of the President, was instructed to keep close watch on how the invested sum was used, and to regularly report to the Board - but did not do so. (Deliberate, management and inefficiency abuse.)

-

- (f) The ExCo failed to monitor the investment, even when the invested sum was not returned within 30 days. It also did not inform the full Board until ten months later, only days before the Members' Annual General Meeting. (Deliberate and management abuse.)

-

- (g) Those members of the full Board and ExCo who were not a party to the investment decisions failed to detect that a substantial part of the organization's assets had been compromised, until the independent audit report 10 months after the event. (Management and inefficiency abuse.)

-

- (h) Middle management staff who knew of the problem failed to report it to the uninformed Board members and the general membership. (Management and inefficiency abuse).

-

- (i) After the full Board became aware of the situation, it initially appeared to attempt to hide the situation from the membership at the Annual General Meeting by allowing the CEO to produce no draft audit accounts. Members at the Meeting forced the issue and finally received copies of the draft audit account. (Deliberate and management abuse).

Example 2

Certain Board members of the national organization wished to borrow money from it. In order to legitimize this action, they consulted the organization's constitution and used a paragraph out of context. The borrowing went undetected during the intial year. Nobody present at the Annual General Meeting questioned this item in the annual audited accounts until the second year. Although the majority of funds were eventually repaid, this action amounted to management abuse, and caused membership to lose trust in the Board.

The organization also approved a $3,000 loan to its CEO, contrary to its own constitution and employment policy. The loan went unpaid even though the CEO (who was responsible for the preparation of salary payments) was supposed to make monthly deductions from his salary and repay the loan within six months. This was management and inefficiency abuse on the part of the Board and deliberate abuse on behalf of the CEO.

Example 3

On appointment, the CEO was advised he would be responsible for his own transport to and from home to the place of work (a journey of about 30 km each way), and that the organization's sole vehicle could only be used on rare occasions when working exceptional, unsociable hours. Yet, soon after his appointment, the CEO began to take the vehicle home on a daily basis.

Nobody took corrective action, and the CEO took more and more liberties as time went by. Often, the CEO would not arrive at work until after normal working hours, thus depriving the organization of the legitimate use of the vehicle. The CEO claimed to be taking the vehicle home each night to ensure its safety, but there was no real reason why the vehicle should not have been parked overnight at the organization's premises. The CEO used the vehicle to transport his children to school and produce from his smallholding to town. This abuse lasted for two years until the CEO's suspension (as a result of the actions described in example 1). It is conservatively estimated that this problem consumed a distance of some 32,000 km and US$ 8,000 of the organization's funds.

Discussion

As a result of the problems described in each of these three examples, this organization lost some US$ 27,000 within the space of two years - 20 per cent of the organization's expenditure over that period. The obvious common factor in all the problems is the action of the CEO. However, in each case the organization also demonstrated a lack of certain helpful characteristics that could have prevented the problem. They are listed here:

- (a) supervision and management of the organization by the elected Executive and Board;

- (b) attention to the job descriptions of elected executives;

- (c) questioning of how resources were being used by staff and the general membership;

- (d) regard for procedures and systems;

- (e) monitoring of decisions and instructions by the Board.

In addition, during the time of these abuses, the organization (under the direction of the CEO) did not keep its bookkeeping up to date. Furthermore, apart from the independent annual audit inspection, nobody attempted to produce meaningful management information from the books of account. Neither did the Board attempt to translate the information in the annual audited accounts into a format which could be understood by the vast majority of members of the organzation, who were not financially literate.

The case study demonstrates the dangers faced by placing too much trust and control in one person (the CEO), and the importance of the role of elected executives as custodians of an organization. It also highlights the need for ordinary members of an organization to help ensure that their organization is being run correctly.

Preventing financial abuse: tips for ordinary members

Ordinary members of an organization are often in the best position to speak out and prevent the kind of abuse described here. The following methods of detecting, preventing and dealing with financial abuse are aimed at those ordinary members.

An organization's members have the right to know what is going on in it. They can and should attend general members' meetings, listen to and read reports which are presented - and speak out if they don't understand these. They can ask the Board to explain more clearly what has been, or is being, done. If members are still not satisfied with the way the organization is being run, they can take the following actions:

- (a) Read the organization's constitution. The constitution is there to protect members' rights, and they may find that they have the right to convene a special general members' meeting to discuss their concerns.

-

- (b) Speak to other members of the organization and find out if they share the concerns.

-

- (c) Write formally to the President, informing him or her of their concerns.

-

- (d) Contact the government Registrar of NGOs or Commissioner for Charities and ask them to make enquiries. As a last resort, if they have strong suspicions that money is being abused, they may contact the police or ask one of the organization's major donors to conduct an investigation.

Basic actions

Financial abuse can be likened to illnesses: some are unpleasant but minor; others start as minor but become critical if not treated; still others can be immediately and obviously disabling or fatal. The three basic actions to prevent the problems caused by abuse are also similar to ways of dealing with disease. In order of priority, they are: prevention; early detection; and management (or treatment).

Prevention is better than cure. It is essential that organizations take measures to prevent financial abuse. Such measures include the following:

- (a) Open, clear and transparent accountability by elected officers and staff. This means clearly defined roles for elected officers and clearly defined job descriptions for staff; levels of responsibility and accountability should be clearly defined along with these.

-

- (b) Wise and efficient use of assets and resources. This includes effective, regular control, monitoring and supervision of assets and resources.

-

- (c) Open, clear accounting and bookkeeping practices where the books of account are kept up to date.

-

- (d) Preparation, monitoring and control of budgets.

-

- (e) Regular banking and primary support documentation for income and expenditures.

-

- (f) Multiple signatures for cheques, financial withdrawals and transactions.

-

- (g) Regular internal auditing by the treasurer, secretary, president or an independent auditor.

-

- (h) Regular periodic (usually annual) auditing by an independent person, preferably an auditor or chartered accountant.

-

- (i) Elimination or reduction of opportunity and temptation for abuse.

-

- (j) Training of the Board and staff in matters such as duties and responsibilities, procedures, systems and handling of cash.

-

- (k) Presence of at least two people whenever cash is handled, as much as possible.

-

- (l) Public announcements that abuses will not be tolerated and that anyone caught abusing the organization's resources will be dealt with severely and publicly.

Early detection. Detection of abuse relies not only on the elected executive, board members and staff, but on all who have business with an organization, including the ordinary membership and donors. In addition to the measures suggested under prevention (above), concerned parties can do the following:

-

(a) Monitor resources and assets. This will include:

- physically checking items against an asset register;

- inspecting vehicle log books;

- examining postage-stamp registers;

- examining petty-cash books and receipts, and reconciling cash on hand;

- carrying out bank reconciliations to ensure that the bank account balances;

- checking time sheets;

- examining random bills and expenses.

- (b) Monitor expenditure and income against the prepared budget.

- (c) Update the books of account.

- (d) Carry out spot checks.

- (e) Ensure that procedures and systems are in place and are being observed.

- (f) Regularly share information between staff, board members and the organization's membership.

- (g) Ensure direct, confidential communication opportunities between staff and Board members.

Swift and immediate management of abuse is required as soon as abuse is detected. Those concerned must immediately stop the opportunity for it to continue. Second,they must investigate the abuse, find out who the perpetrators were, how the abuse operated and estimate or quantify the extent of the abuse. Third, they should introduce systems to prevent the abuse recurring. Fourth, they should deal with the perpetrators and try to recover the lost funds/resources. Finally, they need to decide how to inform the organization's members and, if necessary, the public or donors (possibly including the Government).

Considerations

The following matters should be considered in dealing with financial abuse.

Insurance: Concerned parties should find out how much it will cost to insure assets against theft or loss, as insurance may be one way of limiting the financial damage to the organization.

Legal action: If a particular abuse amounts to a crime, such as theft, fraud or embezzlement, then the matter should be reported to the police. In some countries, reporting a crime is mandatory. Under most legal systems, if criminal proceedings are undertaken, it prevents any civil action for the recovery of funds until after the criminal case has been heard. But in many cases of small abuse, or cases where the perpetrator(s) have no assets, civil action may not be a cost-effective method of dealing with the offence.

Going public: When abuse is detected, openness is generally the best policy, but that does not mean that telling the public immediately is the best choice. The organization should, first of all, keep its members up to date on the situation. If a specific donor's money or assets have been abused, the organization should inform that donor about both the loss and the actions it is taking. Rumour can be more destructive than the truth, so the organization should prepare a press release and send this to various news agencies before any rumours can start, if there is a good chance of the abuse becoming public. A lawyer or legal adviser should check any press release before it is circulated, to ensure that the organization does not fall foul of any libel infringements or jeopardize future court action. The organization should appoint an official spokesperson to deal with enquiries and refer all enquiries to that person, rather than allowing others to communicate directly with the press.

Reports: Those writing reports concerning abuse should refer only to known, provable facts. They should not speculate, assume, presume or use emotive words.

Further training: After taking the immediately necessary actions, the organization may wish to consider providing further training or refresher training for its staff, volunteers or board, in order to prevent or reduce the opportunity for a repetition of the abuse.

Systems and procedures

The most important and effective weapons against abuse are the systems and procedures designed to protect the efficiency and security of an organization and its assets. It is not enough for the systems to be designed and in place; those using the systems must understand them. This may involve training or the production of procedural manuals. Most importantly, staff, volunteers and board must adhered to the systems and put them into practice. This involves management, supervision and discipline. All organizations are different, but in addition to the guidelines already provided in this article, the following general guidelines may be useful.

Primary Documentation (also known as supporting documentation): Recording and secure filing of primary documentation is vital. Primary documentation consists of the pieces of paper used to make or receive payments, such as receipts, invoices, statements, quotations, deposit slips, cheque stubs and bank statements.

Receipts: The organization should write receipts for all money entering the organization, usually at the same time he money is received, and give the top copy of the receipt to the person making the payment. Those collecting cash should generally work in teams of at least two people, protecting them from allegations against them and helping ensure that all the money collected finds its way into the organization. If the cash box cannot be immediately emptied and counted, the organization should give the collectors a receipt for a sealed tin when they return it. When staff or volunteers collect money for fund-raising events (such as dances), they should be issued with a receipt when they bring the money to the organization. Purchasers of tickets do not need a receipt; the ticket itself functions as a receipt.

Banking: The organization should put income into the bank as soon as possible, saving and filing deposit slips or bankbooks. Income receipt vouchers can supplement the deposit slips and provide details of the money's source. The organization should not leave cash in the office premises for longer than is necessary, and staff should not use income for petty cash.

Expenditures: The organization should use payment vouchers, and attach or file any invoices, statements and receipts with them. It should not use ambiguous descriptions, such as "various", "sundry" or "miscellaneous", on payment vouchers. The person who prepares a payment voucher should not also sign cheques. Cheques should be signed by at least two people, usually the Treasurer and the President. The organization should avoid using cheques made payable to "bearer" or "cash", and use crossed cheques. Cash should only be used for small amounts (petty cash), with petty cash vouchers be used for all payments. Someone other than the cash handler should make spot checks on petty cash.

Bookkeeping: The organization should keep books of account up to date, preferably on at least a weekly basis. Someone other than the bookkeeper should periodically check the bookkeeping entries against the primary documents.

Use of non-cash resources: The organization should keep log books or registers for its non-cash assets and resources, such as vehicles, stamps, photocopying, telephones, stationery, premises and furniture. The log books should record who is using the resources, for what purpose. A recent analysis of one organization's fax bills revealed that over 60 per cent of fax machine usage was not related to the organization's work, but by keeping a register, the organization could recover the cost of the non-work-related usage.

Checks, monitoring and reporting: Having procedures and recording information about income and expenditure and use of assets and resources is not enough by itself. The information must be monitored, checked and analyzed. For example, someone other than the invoice writer must examine invoices to make sure that the organization actually received the goods or services and that they were not used by others; non-cash asset registers must be periodically examined; actual expenditures must be compared with budgets. When checks and monitoring are complete, then the board and members should receive the information through reports. Reports may not need to be detailed, but they should provide decision makers and members with enough information to reassure them that the organization's financial affairs are in order and going according to plan.

Appropriateness: Any and all of the above systems and procedures must be appropriate for their purpose and understood by the people who will use them. For example, there is no point in setting up a complex accounting process which requires a qualified bookkeeper or accountant if the organization has no access to anyone with those qualifications, or if it is impossible to get the necessary stationery to support the system.

Case study 2:

Fund-raising in the Fiji Disabled Peoples Association (FDPA)(7)

Development, growth and initial funding of the FDPA

In the 1960s and 1970s, Fijian people with disabilities gathered informally in the capital city of Suva to make their lives more interesting and enjoyable, and to provide mutual support. They bonded through sports, socializing and music as well as recognizing the common bond presented by their disabilities. At this informal stage, members paid their own way.

By the end of the 1970s, there was growing international perception of the need for a reappraisal of policies and social attitudes regarding disability. In response, the United Nations declared the year 1981 as the International Year of Disabled Persons. This prompted Governments and communities to take a more thoughtful and planned approach to disability issues. In Fiji, concerned parties convened to discuss needs and future direction. They soon realized that a great amount of work was needed, and the Government recognized that it could not do everything necessary without assistance from NGOs. The United Nations initiative gave people with disabilities confidence that their concerns were legitimate and that they had the right to attempt to improve their lives and opportunities. Incorporation of the Fiji Paraplegic and Disabled People's Association soon followed in 1983.

Through the 1980s interest continued to increase and several formal events were undertaken, including sports, training, and seminars/workshops. The group was still largely self-funding, with sporadic injections of project-specific funding from outside donors. Often the donor organizations initiated these grants. Management of the group was by consensus, and volunteers provided what little administration was needed from their own resources. Thus costs were kept to a minimum. Social and community events were organized which included modest fundraising through raffles, card games and gunu sede(8) activities. These funds were used for social and sports events, contributions to members in need, purchase of medical supplies and the like.

In 1988 the Association renamed itself the Fiji Disabled Peoples Association (FDPA), acquired permanently rented office premises, and took on its first full time employees, one local officer and one Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) volunteer. This milestone in FDPA's history was the beginning of a continuing and largely rewarding relationship with the media and local business houses. Representatives from Government and other prominent personalities attended the office opening and contributions from the business community for furniture, equipment and stationeries were received. The presence of the British Ambassador and the British Government's willingness to underwrite initial costs added prominence and respectability.

The opening publicity generated a further leap in awareness of disability issues and raised expectations of those with disabilities. Such expectations themselves were a generating force; the Association's Board and staff had to become performance-oriented. Not only that, but they had to show the public what they were doing, involving accountability and further use of the media.

This full-time presence of the Association came, of course, at a dollar cost. Regular funds were now needed to pay core costs, such as rnt, electricity, rates, salaries, stationery, telephone, postage and insurance. From 1988 until 1994, the British Overseas Development Administration (ODA) provided 100 per cent core funding for FDPA. Annual grants from ODA were released on a quarterly basis against a submitted, costed annual budget. ODA was assisted by the Pacific Field Office of VSO, the British volunteer sending agency, which provided local monitoring and implementation support.

Core costs are the essential costs involved in keeping the organization operating but do not include project specific costs. In other words, they do not include costs of launching and running individual projects, such as workshops, the production, printing and distribution of posters, brochures and newsletters, and community-based rehabilitation programmes. Funds to operate projects had to be self-generated, or funded from other sources, such as corporate donors or Governments.

In addition to undertaking a monitoring role, VSO assisted the Association by providing qualified British development volunteers from 1988 to the present time, with a one year gap in 1993-4. Until 1996 the in-country costs of these volunteers were included in the core budget funded by ODA, while VSO funded flights and the remaining volunteer support costs.

ODA core funding of FDPA had grown from less then F$20,000 in 1988 to F$92,000 for 1993. 1993 was also the year ODA carried out a major review of its grant in aid to the Pacific, and in the context of a global rationalization, ODA took the decision to negotiate a planned withdrawal from funding of disability programmes in the Pacific.

Clearly, this was going to affect FDPA greatly, and the Association had to prepare itself to become more financially independent. With funding from ODA, the Association was encouraged to consider longer-term strategic and operational planing. A series of planning meetings and seminars were held which culminated in October 1993 when the foundations for the future operation of the Association were laid, and FDPA's first three year strategic and operational plan was agreed on. Withdrawal by the donor was negotiated on the basis of the plan, with ODA agreeing to fund 100 per cent of core funding in 1994, 50 per cent in 1995 and 30 per cent in 1996, thus giving the Association the chance to progressively adjust its core funding base.

FDPA planned to meet its core costs through a simple strategy. It would review all planned activity and divide anticipated costs into one of two categories - core costs, or project costs. Core funds, raised through fundraising, member subscriptions and income-generating activities, would meet the essential costs of keeping the Association and office functioning. Project funds, on the other hand, would be sought from Government and other donors to meet specific project-related costs. If project funds were not forthcoming, then expenditure could be deferred until funding became available. Although this strategy was simple, it was not easy to implement. There was initial reluctance by the Board and Chief Executive Officer to identify staff who were to be designated as project-specific, and their costs continued to be a burden on the core budget. This process was not begun until 1996, by which time unhealthy inroads had been made into financial reserves. Neither did FDPA initially identify and quantify income and cost centres, nor exercise effective budgetary control and monitoring. As a result, valuable time was lost and scarce reserves consumed on core costs. Others would do well to learn from this experience: if a strategy is devised and agreed upon, then it should be implemented without delay.

Common methods of fund-raising

For fund-raising, FDPA first considered the conventional methods, which are tried and tested and have proved their worth over the years. These methods include the following list (which is not exhaustive):

- (a) Dances and balls;

- (b) Musical events;

- (c) Raffles;

- (d) Sponsored walk- or wheel-a-thons;

- (e) Bring-and-buy (jumble or garage) sales;

- (f) Street collections;

- (g) Barbecues.

FDPA successfully raises approximately 40 per cent of its headquarters' core operating costs through these activities, and branch offices rely almost entirely on them. Their success depends on good publicity, the use of the media, and the good will of friends of the Association who provide services or goods, such as entertainers or event venues, free of charge. This type of activity can be time-consuming to organize, and may lead to "donor fatigue" if held too often(9). FDPA has found that nine to ten events of this kind each year is about optimum in Fiji.

FDPA saw a need for continued, sustainable income and for professionally produced project proposal submissions. In response, it appointed a full-time Project Development and Fundraising Officer. Organization which do not need full-time officers may wish to set up a Board sub-committee using volunteers to carry out this work.

Fundraising guidelines

Organizations should consider the following guidelines in raising funds:

- (a) Emphasize the "fun" in "fundraising"; give supporters entertainment and value for their money.

-

- (b) Make the proper provision for financial accountability. Properly number the tickets for dances, balls, dinners and raffles, and the sponsorship forms for walk- or wheel-a-thons.

-

- (c) Record the ticket numbers given to sellers, to keep track of how much money should be returned. Issue receipts to ticket sellers when they return money from the sale of tickets.

-

- (d) Give some complimentary tickets to those who have provided services free of charge or otherwise been especially helpful. Remember, however, that the object of the exercise is to raise money. Keep a record of the complimentary tickets.

-

- (e) Carefully record expenditure and income for each event so you can see how much net income the event has generated.

-

- (f) Publicize the event. Call on the media, use posters, telephone or fax known supporters, advertise, etc.

-

- (g) Evaluate the event. Compare one event with another. This will help identify criteria that make for a successful event. Identify which events were more successful than others, and analyze what factors may have made them successful (e.g., weather, timing, location, publicity, value). Decide whether the investment of time and money was worthwhile; in doing so, take into consideration the subsidiary benefit of these events, which is to generate public awareness of the organization and the issues.

-

- (h) Involve members in fundraising, as ticket sellers or organizing volunteers. Member participation is important. It gives members a sense of purpose and belonging, nd a feeling they are doing something worthwhile for their own cause. It also demonstrates members' interest in what is being done, and raises awareness by showing that people with disabilities can have fun and participate in community activities.

-

- (i) As far as possible, make event venues fully accessible to members and convenient for the supporting public.

-

- (j) Remember legalities, formalities and courtesies. The organization may need to seek formal permission for an event, or obtain a licence from the relevant authority. For example, raffles may be subject to legislation dealing with gambling, or street collections may need permission from local government authorities, District Officers or central Government. In some cases it may take time to obtain a licence. Plan well in advance (including publicity). If there is doubt about the legality of the event, check first with the police or local authority.

-

- (k) Any event occurring in a public place may require approval by police or local government authorities, or both. Even if approval is not required, police should be informed, provided with the time of the event and invited to be present if money will change hands in public places, or if there may be a traffic hazard from people using roads (such as in sponsored walks) or from parked cars.

-

- (l) Thank all those who helped and supported the event, regardless of how successful it was. The organization will surely need their help again. In addition to thanking people personally, FDPA usually places an advertisement in the daily newspaper; this also provides an opportunity to publicize the organization further.

-

- (m) Emphasize novelty and variety. Regular social events are generally not successful, as supporters become bored with attending the same thing time and again unless one can find the right market niche. FDPA has tried to add variety to dances and musical events by introducing different "themes"; e.g., jazz, cowboy night, rhythm & blues, music and dress from the 60s and 70s, masquerades.

Special events

In addition to the more conventional fundraising activities described above, FDPA organizes three or four special events each year. These are useful in providing a supplement to the more regular fundraising activities and, with co-operation from the media, usually focus a higher level of publicity.

Auctions: Businesses and other organizations often find it easier to donate goods and services rather than cash; auctions use this fact to an organization's advantage. FDPA wrote to a number of businesses seeking donations of goods to be put up for auction. This attracted gifts of plane tickets, restaurant meals, resort and hotel accommodations, electrical appliances, household items, sporting goods, and more. (FDPA then raised the value of two donated rugby balls by inviting the winners of the regional under-21 rugby tournament to sign them.) The auctioneer was a prominent hotelier; the auction included some small, cheap novelty items (such as a hot water bottle) so that everyone could join in the bidding. The British Ambassador and family offered a prestigious venue for the auction. FDPA billed the event as a "Cheese and Wine evening with Auction" and sold tickets at $6.00 each. FDPA contacted embassies, diplomatic missions, grocery store owners and others to provide of cheese, wine and snack foods; the response was better than expected, demonstrating donors' good will. The auction was a splendid evening and alone raised over eight per cent of FDPA's annual core cost target.

Film premiere nights. An orgaization can persuade a local cinema to allow the NGO to sell tickets to the opening night of a new film. A fixed charge, paid from ticket sales, is made for the use of the cinema. Usually, because it is an opening night and for a good cause, people are willing to pay a little more for their tickets. A film dealing with disabilities, such as "My Left Foot" or "Shine", is ideal, but not essential.

Marathons. Over the last three years FDPA (Rewa Branch) organized two around the island wheel-a-thons. The most recent of these was intended to raise funds for the building of a branch office and meeting hall. The wheel-a-thon took a week from start to finish, covered a distance of approximately 450 kilometres and was a high-profile media event. Prominent community figures opened and closed the event, and welcomed the team in each major town and city en route. FDPA informed schools, businesses, town councils, hotels and restaurants along the route of the date and time of the team's arrival, so that collections could be held and refreshments provided. A national vehicle dealership provided support vehicles and drivers free of charge. A telephone company donated a cellular phone and paid call charges. This enabled the team to keep in touch with the FDPA office and, importantly, with the media, who could then relay several live radio broadcasts. A great deal of advance preparation, logistics and co-ordination, involving well over 150 letters or faxes and numerous telephone calls, were required to make the event a success.

Chartered Ship. FDPA's Suva branch, with assistance from the owners of a ship, recently organized a round-the-bay sunset cruise. Poor weather made this event less successful than anticipated. Fortunately, the Suva branch took the precaution of having the event underwritten by the ship's owners, so that if it failed to raise sufficient funds to meet direct costs, the branch would not be left holding the bill.

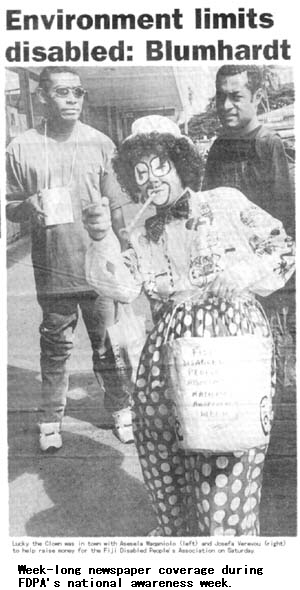

National Awareness Week

Since 1988 FDPA has declared the first week of June each year as a week for national awareness. The week includes elements of fundraising and membership recruitment. This is FDPA's largest single fundraising activity of the year; it is sponsored by radio, TV and the national press. In past years, the week has contributed up to 35 per cent of FDPA's annual core costs. Because FDPA has been regular and reliable about holding the awareness week, the media and regular donors now know each year that the week will take place, and make arrangements accordingly. In addition, other NGOs know that this is the FDPA fundraising week, and generally do not schedule their events to clash with FDPA.

Planning begins months in advance and involves not only the Fundraising and Project Development officer, but the entire staff and many volunteers from affiliated NGOs and members. The week is not a single event but a series of events, at least one on each day of the week. Some events are pure fundraising, some directed towards members, some directed to Government or other specific targets, some for awareness raising and education, and some just for fun. The week is a team effort, but it takes a tremendous amount of organizing. The Fundraising and Project Development officer has to use all his or her skills in management, supervision and delegation to coordinate and make sure that events go ahead on time and as planned.

In past years, FDPA has assisted with Gold Heart day, a day organized by Radio Fiji and the Variety Club to raise funds for children with disabilities, to ensure that the week has maximum publicity and coverage. FDPA assists Radio Fiji with its Gold Heart day by selling gold heart badges and returning the proceeds to Radio Fiji, which in turn passes them on to special schools. Radio Fiji reciprocates by providing FDPA with significant publicity for the week, advertising events nd broadcasting interviews with FDPA staff, members, other disability-oriented NGOs and relevant government officers. In addition, Fiji TV One provides advertising to FDPA and Radio Fiji for their fundraising efforts, and both major daily newspapers cover events and usually print disability- awareness supplements.

It is useful to have a special emblem or mascot for the week with which the general public can identify. The Gold Heart badges provide this to some degree, but FDPA also has its own mascot: Lucky the clown. The clown (a member of the staff made up in a clown's outfit) is present at all events and tours the town during the late afternoon and evenings, visiting night clubs and other entertainment centres.

The "week" actually lasts eight days (Saturday to Saturday inclusive). This way, it is possible to have both the opening and closing event on a Saturday, when a good public turnout can be expected. During the opening and closing events, the business community and the media contribute to awareness week by providing venues, entertainers, entertainment, services and prizes at free or reduced prices, and patronizing events. Business staff also provide assistance by setting up and attending stalls and carrying out collections. This helps to minimize costs, maximize the financial benefits to FDPA and provide supporters with enjoyable and exciting events.

Future special events

The United Nations has declared an International Day of Disabled Persons, to raise the general public's awareness of the needs and rights of people with disabilities. By making use of the general publicity surrounding the day, NGOs can enhance their own fundraising and awareness-raising activities.

FDPA has also begun talks with the Fiji Philatelic Bureau to discuss getting a first-day stamp issue dedicated to the Association's work. Pre-planning is essential for a promotion like this; the Philatelic Bureau has already determined its first-day stamp issues for the next two years. In addition, the FDPA is considering issuing its own limited-edition first-day covers (envelopes), which may be marketed through prominent international philatelic concerns.

Membership fees and internal fundraising.

Membership fees are one way of raising funds, but they must be considered carefully. People generally join an organization to get some benefit from being a member. The primary purpose of FDPA is to advocate and lobby on behalf of people with disabilities, and the benefits of membership may not be immediately apparent to individual members. Furthermore, FDPA's strength is that it speaks for a large number of those with disabilities, and many prospective members claim they cannot afford membership at $5 per annum. Organizations must ask whether they want a large membership at a nominal membership fee, or a small membership at a larger membership fee. Note that, although 1,000 members paying $1 each raises the same income as 200 members paying $5 each, with 1,000 members the organization has a greater voice, more impact, and more opportunity of raising funds. For these reasons, FDPA will review membership fees at its next annual general meeting.

Internal fundraising means raising funds from members. In 1996, FDPA tried to return to its social origins and resurrect a members' Social Club. A three-person committee, two members of which were staff, organized weekly events for members. Initial response was good, but the number attending events fell when people realized that not all profits were returned to the direct benefit of the club itself. (About 50 per cent of profits went to the club, with the remainder contributing to FDPA's core costs.) Organizing events was draining on staff who volunteered time, and after less than six months, the club expired from lack o interest by members. The club had contributed about $200 to core costs and purchased assets such as a vidividi board, dart board and playing cards. The lesson to be learned is that fundraising through internal social events should be driven by membership demand, rather than imposed. Interestingly, less than a year since the club ceased, the members themselves now wish to reconsider its establishment.

Other ways of internal fundraising include selling goods (such as greeting cards, calendars, or novelty items) to members at discounted prices, through over-the-counter sales or mail order. This has worked for FDPA when a corporate supporter (an exporting clothing manufacturer) donated clothing "seconds" to the Association for onward sale to its members(10). Future items for possible sale include a souvenir presentation calendar planned for the year 2000; the calendar will feature the 12 posters to be developed between 1997 and 1999 as part of the "Celebration 2000" advocacy programme.

Income-generating activities, corporate donors and sponsorship

FDPA has not yet established any sustainable income-generating activities. However, it is currently setting up two such activities. The first of these is a facility for repairing, refurbishing and manufacturing wheelchairs and other assistive devices. Several years of research and planning have already been carried out, including a market-research study conducted by students and staff of the University of the South Pacific. The South Pacific Disability Trust Fund and commercial groups in New Zealand have offered financial and technical assistance. The business will require an initial investment of approximately $20,000.

On a smaller scale, the FDPA "Pathfinders" youth group will shortly start making paper by hand, using recycled materials. Initially, this will be a small-turnover, high-value product directed mainly at expatriates and tourists. It is labour-intensive, involving little capital and therefore low risk; such a situation is ideal for youth groups and self-starters. The same youth group is researching the feasibility of setting up a regular car-wash business as a project to generate employment and income for youth.

Any income-generating project is a business. As such, it is likely to be in competition with other businesses, and must be operated efficiently and effectively on commercial lines if it is to succeed. The organizers of such a project must carry out market research to find out who, if anyone, will buy the product or service in question before committing a large investment. Note that feasibility studies should include provision (through a depreciation reserve) for reinvestment of capital equipment.

Other possible business schemes include collecting used stamps and telephone cards for sale to collectors.

Publicity and the media

Publicity, usually generated through the media, is critically important to achieving the primary objectives of many self-help organizations: to bring about awareness of the issues, to educate the general public, to lobby on behalf of people with disabilities and to raise funds for continued operation. Without media and other publicity, FDPA would be muted and less effective.

FDPA has carefully fostered a relationship with the press, radio and television. It has found the following actions generally effective for an organization dealing with the media:

- (a) Encourage the personal support of people in the media, inviting them to events. Familiarie them with the organization, its goals and ambitions, and especially its needs. Solicit the ideas of media people, so that they become involved.

-

- (b) Make use of the free community-service announcements provided by many television stations, radio stations and newspapers.

-

- (c) Give the media interesting stories about the organization, what it is doing, and what it needs.

-

- (d) Avoid being too demanding. Asking too much too often can earn the tag "here they come again". One large request can be better than many small ones.

-

- (e) Plan yearly requirements. Sit with media representatives to discuss working together.

-

- (f) Be prepared when asking for media assistance. Fully explain the event, how it is to be run, where funds raised will go, how much will go on event expenses, and why media assistance is needed. Ask for their professional suggestions of how they may best be of assistance.

-

- (g) Show media representatives how they may benefit from being involved (e.g., through banners and other media recognition of their participation).

-

- (h) Have a definite person in the media to contact. Ask who else to deal with; do not go to a higher level of the media organization, ignoring the main contact person.

-

- (I) Never ask for personal favours while on the air, regardless of how close a relationship may be with a media representative. It will likely annoy and embarrass them.

-

- (j) Suggest personality involvement. Ask who to send new releases to, how often would they like to receive them, and whether there will be opportunities for live interviews and name association.

-

- (k) Make sure to follow up every point discussed with media representatives in writing. As well as making it more likely that requests will be granted, this demonstrates a professional approach.

-

- (l) Since media organizations are looking for a marketing advantage in being associated with charitable organizations, give them something to work with.

-

- (m) Put forward many ideas. The more ideas advanced to the media and the more ways media organizations can benefit, the better the chance of getting them involved.

-

- (n) Never take the media for granted. Show them you are grateful for their support.

Contact details:

- Fiji Disabled Peoples Association

- 355 Waimanu Road, Suva,

- G.P.Box 15178,

- Suva, Fiji

- Tel: (679) 311203

- Fax: (697)301161

Case study 3:

The Women's Committee in the Asian Blind Union(11)

Introduction

This study is about the development of a focus on gender issues within a self-help organization of blind people. It describes events responsible for the creation of a women's committee in the Asian Blind Union (ABU), as these are directly related to blind women's increased participation in ABU. Some of the facts described within may annoy or hurt some colleagues, but the purpose of narrating those facts is purely constructive - to share ABU's experience with women with disabilities in other organizations who may have faced similar difficulties. They may be encouraged in assuming a more active role in the self-help movement if they find their experience is not so different from that of the women in ABU.

ABU is one of the seven regional unions of the World Blind Union (WBU), a single international forum of organizations for the blind in the world, whose members come from 170 countries and belong to 600 national-level organizations. Every country has a certain number of seats in WBU; each delegate represents his or her organization and country. Delegates are often the leaders of a national organization. WBU and ABU have executive boards and sub-committees to look into specific areas of concern. The Committee on the Status of Blind Women enjoys a special status of importance in WBU. The chairperson of this Committee becomes the ex-officio of the executive board and all regional unions. This arrangement is supposed to be replicated in the regional unions of WBU.

The regional union's chair is elected or appointed by its executive. The seven regional chairs and the international chairperson of the women's committee form the international committee on the status of blind women at WBU. Similarly, the national organizations are expected to have a focus on gender issues, and to this effect, a formal structure is also expected to function at the local level.

WBU and its regional unions derive knowledge from the experience of national-level organizations; in turn, WBU disseminates the knowledge it gains through its world-wide network. WBU is built on this foundation. The developments and concerns of the national organizations influence the workings of WBU and, above all, the policy decisions at the international and regional level.

Gender concerns surfaced in the WBU at its very inception, but have gained momentum in the past decade. The relatively low participation rates of blind women in WBU and its regional unions have helped lead to a fairly gender-indifferent environment in the organization for a long time. But gender representation has become more balanced at the physical, intellectual and functional levels within WBU over the past decade. This is well recognized, and it has a clear bearing on the thinking and functioning of WBU's regional and national affiliates.

NAB: a national affiliate in ABU

The National Association for the Blind (NAB) in India is one of the national affiliates of WBU and ABU. It has two seats on the boards of WBU and ABU. In the early 1980s, a committee on the status of blind women was set up in Bombay at the NAB headquarters. This action resulted in the setting up of an impressive women's department at Ray Road, Bombay. The department looks like a small institute, but undertakes several activities for the empowerment of blind women. These include training in leadership, communication and independent trvelling skills, home management, switchboard operation, tailoring, jewellery making, packing and assembly-line operations. The centre has a marketing division that ensures the sale of products in national and international markets. The department brings out a women's magazine, and has also instituted a Neelam Kanga Award to recognize outstanding professional blind women. Similarly, the branches of NAB in Haryana, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi have a focus on gender issues. NAB Gujarat, in collaboration with the Blind Men's Association, implements a large Community-Based Rehabilitation Project which allows wider contact with blind women in rural and developing areas. Despite the sensitivity at NAB towards special concerns of blind women, both seats at the WBU were represented by (very capable) male NAB members until 1996, even though there were blind women with outstanding abilities within the organization.

History

In 1993, NGOs were forming forums at the state and city level to lobby for the enactment of a comprehensive law to protect the rights of people with disabilities in India. The meetings of such forums would often involve two or three women and 20 to 30 men. Women would often encourage each other to attend these meetings; those who were mobile would help others who could otherwise not reach the meetings. The women put forth some gender-related suggestions to be included in the draft bill for which the Government of India had invited the views of people with disabilities. These suggestions were not included, as many male colleagues believed gender-specific recommendations in a law would be inappropriate.

In 1994, the committee took an initiative to review the impact of its existing policies and programmes, as the members felt an acute need for change to make them more relevant. A new charter of the committee was drawn up and a memorandum of demands, based on this exercise, was submitted to the Welfare Minister of the Government of India. At this time, NAB involved Mrs. Promila Dandavate, a veteran women's leader of a political organization, to help bring about unity with larger women's organizations. Together, they attempted to get recommendations more favourable to women incorporated in the Disability Act.

As enacted in 1995, India's disability law has only two clauses targeting women: one to ensure the representation of disabled women on all the decision-making bodies envisaged in the Act, and one to submit a gender-disaggregated report on the implementation of the Act by the Chief Commissioner to the Parliament. Women in NAB were not satisfied with this arrangement, but were happy that the law ensured some visibility of the women in policy matters as a starting point.

The first gender meeting in ABU

In June 1995, owing to the obligation of the newly enacted law, the Government of India included one blind woman in the official delegation to the United Nations to take part in the ESCAP Meeting to Review the Progress of the Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabled persons. Sawart Pramoonslip of Thai Blind Union invited the author to participate in the proceedings of their meeting on 25 June 1995. In this meeting, other blind women participating in the ESCAP Review Meeting were also present; they came from Bangladesh, Bhutan, Fiji, Indonesia and Thailand. The main issue discussed at this meeting was blind women's low rate of participation in ABU; out of a delegation of 42 from Asia to WBU at the time, there was only one woman delegate. Indeed, in the history of ABU, there had never been more than one woman delegate. This became a matter of concern for all who were present at this meeting. Another problem was that the Women's Committee of ABU had no Chair during the current term.

Attenders of the meeting made the following suggestions and cnclusions:

- (a) Women in Asia should use the period between June 95 and June 96 in preparing themselves for taking part in the Fourth General Assembly of ABU, in which they could ensure that a Chair would be properly appointed for the Women's Committee;

-

- (b) Women should share their concerns with each other and keep each other informed of the happenings in their countries, enriching each other with such knowledge;

-

- (c) Women should form an informal working group and elect a convenor (the group was formed and a convenor, Anuradha Mohit, was elected at the meeting);

-

- (d) Women were not visible at the regional and international level because only a few women held important positions in the NGOs, although many women were active at the lower level of the NGOs' functioning.

The participants in the Bangkok meeting returned in high spirits with a new awareness and a determination that gender would be included in their organizations' agenda at the local level. The objective was to emancipate women from the confinement of ignorance, economic dependence, low self-esteem and low aspirations, and above all to create a society free from the fear of physical, emotional and mental exploitation, within the parameters of their limited strength, limited access to information, and resources.

A war of letters

One Indian man soon sent a letter to the Chairperson of ABU. The letter writer had strong reservations that giving recognition to the informal blind women's group might keep on hold all the rules and regulations of WBU. He also abhorred the idea of Asian women imposing an Indian as their convenor. After a few days, the Chairperson of ABU sent a reply which supported the objections raised by the "law-abiding ABU delegate" and levelled charges against the Secretary General of WBU.

The Secretary General's reply expressed full support to the rule of law and sanctity of the constitution, but underlined the need to further the struggle for the rights of visually disabled women and the need to take a positive view of the matter. He emphasized the importance of participation of regional bodies in the work of WBU. He also advised the letter writer to respect the decisions of women members in having elected a woman convenor themselves. This exchange of letters went on for a number of rounds. It made women members more aware of the need for circumspection and of their active role in ABU. They realized that they would need to be vigilant and tactful, differentiating friends from foes. Above all, they would need to attract more blind women into their organizations.

The fourth General Assembly of ABU - new challenges, new success

After a great deal of effort on their part and that of sympathetic senior members, three women attended the Fourth General Assembly of ABU on the official delegation, one each from India, Malaysia and Thailand. They had actively lobbied with their male colleagues from national organizations to get the working group of blind women ratified for official status by the ABU Assembly - a difficult task. They also participated in the General Assembly discussions on comprehnsive planning of education of the visually handicapped and employment of blind people. All the women participants were cooperation in the deliberations. One participated in the Resolution Committee. Above all, the women delegates gave evidence of their mature understanding in their efforts for furthering the cause of women's participation.

On the third day of the Assembly, elections to all the posts were conducted and completed except for the Chair of the Women's Committee. Suddenly signs of tension began to be felt in the otherwise positive and congenial atmosphere. Tension, barely perceptible at first, slowly started building up. And then, it was revealed that the ABU Chairperson had virtually turned down the proposal for appointment of the Women's Committee Chairperson.

Women delegates were determined to use all available options to turn the decision in their favour. They approached representatives of funding agencies, officers of WBU, women sympathizers and sympathetic male delegates for their help. Together, they persuaded ABU to display a more positive stance towards the selection of a Women's Committee Chairperson.

The ABU Chairperson spoke in stringent tones about outside interference, which he said he could not tolerate. He had, therefore, deferred the election to the post of Chairperson. But he soon abandoned this position and announced that Anuradha Mohit could make positive contributions to the work of the ABU as the Chairperson of the Women's Committee. He invited other nominations. As none came up, her election was unanimous. Despite the questionable circumstances, most colleagues promised support to her and women delegates adopted an encouraging tone.

Preparation of the report on the status of blind women in Asia

At the first World Blind Women's Forum in Toronto, women members of ABU were asked to present a report on the status of blind women in Asia. This was a difficult task, partially because time, information and resources were scarce, and also because women with disabilities were not in the habit of documenting their experiences or observations (especially in a foreign language like English), making it difficult to express their views.

Immediately after the appointment of the Chair of the Women's Committee in Asia, the committee had its first time-bound assignments. This provided a new found incentive to make blind women active. They were busy rummaging through files and reports available from NGOs and libraries. Most of this information was in the control of men, who occupied important positions in the organizations. However, women in Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka got full support from their male counterparts in compiling gender-relevant reports for the world forum. They had to cull information from the contents of the reports presented by Governments and NGOs at various international forums. There was hardly any direct reference to the information they sought, but the exercise gave them insight into the thinking of women's organizations and the international and national stands on the rights of people with disabilities generally. They did benefit substantially from the publications of ESCAP and the International Labour Office. They presented an 82-page report entitled "Coming to Light" at the Forum, which addresses a comprehensive range of issues.

Second informal meeting of blind women

Eleven Asian women participated in the first World Blind Women's Forum, from nine different Asian countries. They took a day to reflect on the decisions taken at the World Forum, consolidate gains and chalk out a tentative agenda for the ensuing Women's Committee in Asia. Highlights of their meeting were the following:

- (a) Women felt there was an absence of a forum within national organizations to articulate their concerns and ideas, as most national organizations have either a weak women's committee or none at all.

-

- (b) ABU should use human and material resources in its empowerment programmes to reverse the illiteracy, unemployment and low social status of blind women.

-

- (c) The media should be sensitize to blind women's concerns, thus moulding public opinion in their favour, generating a national debate around their issues, developing skills among blind women for writing articles and documenting experiences in order to share them at all levels.

-

- (d) Blind women need leadership training seminars and workshops at all levels, taking into consideration the different needs and levels of understanding of blind women.

-

- (e) The women's committee should take steps towards developing and strengthening blind women's networks at local, national and regional levels for sharing expertise, skills, experience, material and information in order to empower each other and build their solidarity.

These concerns had a direct bearing on the emergence of the Plan of Action of women's committee in Asia today. This meeting was extremely useful, as they had anticipated little other possibility of direct interaction in the near future, and their past experience of international forums had involved limited benefit, as participants often did not get the opportunities to reflect on the decisions and plan future agendas in the light of collective decisions that emerged.

Towards activating a women's committee

In the fourth ABU General Assembly at Kuala Lumpur, women were determined to create a modest and functional Women's Committee in ABU. A formal request was sent to the ABU Chairperson forwarding nominations for the members of Women's Committee, followed after several weeks by a reminder, and then another reminder. But all efforts proved futile; no nominations were obtained. There was little cooperation from the heads of the national delegations, who were supposed to forward nominations.

In February 1997, Ms. Mohit, Chair of the Women's Committee, wrote a letter to the ABU Chairperson requesting him to facilitate a meeting of the Women's Committee to develop a plan of action. In this letter, she did not ask for forwarded nominations of committee members; she proposed a developing action plan assuming that all the active women members from different countries were official colleagues. The response was prompt and encouraging.

However, the women knew they could not sit together to complete the plan. They had to use documents like the minutes of the ABU General Assembly, the Toronto meeting of Asian Women and the Bangkok meeting of 1995, as well as the Resolution of World Women's Forum, the Agenda for Action for the Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabled Persons and the country papers included in the "Coming To Light" report. All these documents reflected the concerns of blind women from Asia to some extent, making it possible to safely develop a draft action plan.

The plan was sent for review and comments to all the women colleagues in Asia and also to some officers of WBU and the Chairperson of ABU. Most sent in their comments and observations which were incorporated in the second draft. All this was sent to the blind women members in Asia, as they have the final say on the action plan. Their suggestions and modifications were inorporated in the final plan, and then on behalf of the women's committee it was submitted for financial support to the ABU Chairperson and a Norwegian donor agency. The Chairperson soon granted approval of funds.

Second meeting of the executive of ABU

A constitution committee was created to fine-tune rules of operation and make suitable amendments to the ABU constitution in the light of decisions taken at the 4th WBU General Assembly and the amendments made in the WBU constitutions. The Women's Committee used this opportunity to raise the following concerns:

- (a) One woman member should be included in the constitution committee, to ensure that due note of women's views is taken while framing the rules of operations in the constitution;

-

- (b) There should be at least one woman member in all the sub-committees of ABU;

-

- (c) Complete parity of male and female members in all the delegations should be achieved in a phased manner by the turn of the century.

During the September 1996 meeting of Asian blind women in Toronto, they had discovered each other's strengths and weaknesses. They consciously used this to include at least one blind woman on every sub-committee in ABU. Khezan's skills could benefit the sports committee, Jasmine's experience in accounting could benefit the ABU finance management system, Sawart of Thailand had deep interest in the question of employment and Leena of Bangladesh had a good knowledge of several languages and was interested in education.

Activities of the ABU Women's Committee and resource mobilization

NAB had indicated at the executive meeting at Kathmandu that they would only be able to partly finance implementing a plan of action for a period of three years in seven Asian countries. When this was clear, the Women's Committee approached the Swedish and Danish Associations for the Blind. After two rounds of discussions, it was agreed that the plans in Nepal and Sri Lanka could be financed by the Danish Society. NAB could take care of the plans in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Thailand. Malaysia was in a position to raise funds internally. As for India, NAB and SRF Sweden agreed to share the responsibility.