V. Approaches and activities

Although many self-help organizations focus their activities on advocacy and awareness-raising, there is a trend among them toward providing support services for their members, for the following reasons:

- (a) There are not enough services to enable people with disabilities to participate actively in community activities;

-

- (b) Existing services, in many cases, do not meet the actual needs of people with disabilities;

-

- (c) Organizations recognize the capability and resourcefulness of disabled people as service providers and their aspirations for meaningful participation in community life.

Traditional service-delivery disability organizations are usually run by people without disabilities. Such organizations tend to consider people with disabilities as passive beneficiaries, rather than giving them a chance to participate in organization decision-making. Increasingly, people with disabilities are challenging those traditional organizations to include people with disabilities as full members in their decision-making bodies, and thereby enhance the relevance of their services to people with disabilities. At the same time, organizations run by people with disabilities can provide direct support services that are unique and cannot be provided by the traditional service-delivery organizations; e.g., peer support services.

In this connection, a good balance is required between advocacy and service delivery. Without support services, people with disabilities may not survive or be able to leave their homes. But if organizations' advocacy work is weak, it is difficult for them to improve the overall situation of people with disabilities.

This section will introduce examples of various approaches and activities. Strong management skills and discipline will be required to implement them, as the more service programmes a self-help organization is involved in, the more it will need administrative efficiency.

A. Approaches to rural people with disabilities

Many self-help organizations are based in urban areas and neglect the needs of disabled people in the rural areas. They tend to focus on accessibility, independent living and other issues that most concern urban disabled people, especially those who are educated and have more access to resources. However, there are many people with disabilities, particularly in the rural areas, who do not have basic services, cannot afford the necessary assistive devices (such as wheelchairs and hearing aids) and are confined indoors for their entire lives.

Therefore, there is a strong need for the development of new approaches by self-help organizations to meet the needs of rural disabled people. Those new approaches require an extensive management review of current priorities, including collaboration with communities, NGOs in social mobilization and government agencies.

Case study 5: Sanghams of village people with disabilities

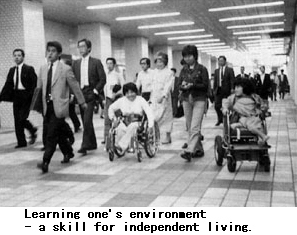

B. Independent-living programmes for people with extensive disabilities

Independent-living programmes in North America made it possible for persons with extensive disabilities to live independently in the community. That movement, in turn, had made great impact on the Japanese disability movement. Japanese disabled persons, inspired by North American independent living principles, adapted independent-living programmes to Japanese culture. Recently, independent-living centres in Japan hae become a visible force in influencing municipal and central government policies and programmes concerning persons with disabilities.

Case study 6: Independent-living centres in Japan

C. Cooperation between self-help organizations in developed and developing countries

There are various ways to enhance collaboration between organizations of people with disabilities in developed and developing countries. The following are two of many such examples.

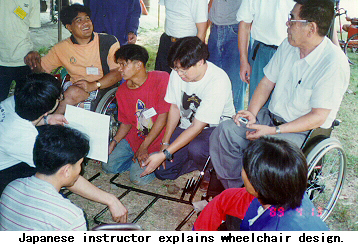

Regional networking in wheelchair production was initiated in 1991 as a used-wheelchair recycling programme for Thailand by Asahi Shimbum Newspaper Social Welfare Organization and self-help organizations of people with disabilities in Japan and Thailand. It has expanded its scope and geographical area. It now includes training of technicians in the production of wheelchairs using locally available materials. There is scope for Disabled Peoples' International (DPI) Asia-Pacific Regional Council to build on this initiative and serve as a focal point for a wheelchair production network, involving DPI members.

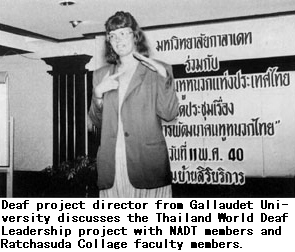

A Thailand World Deaf Leadership (WDL) project will be a joint endeavour of the National Association of the Deaf in Thailand (NADT), Ratchasuda College and Gallaudet University. The Project not only provides the training necessary for NADT members to become professional teachers of Thai Sign Language, it also provides deaf people with university credentials that certify them and them alone as the official teachers of Thai Sign Language. Also, built into the training program is a curriculum and materials development component that assures that NADT will have access and control over Thai Sign Language teaching materials. Furthermore, by hiring Deaf graduates of the program to teach hai Sign Language at Ratchasuda College, NADT is assured input into and quality control over programs related to Thai Sign Language at Ratchasuda College. Such input and quality control is available to no other national association of deaf people in the Asia-Pacific region at present.

Case study 7: The Campaign to Send Wheelchairs to Asian Disabled Persons

Case study 8: A university-level Thai Sign Language certificate programme

D. New types of training and job placement

New types of vocational training/new areas of employment opportunities for people with disabilities are currently being sought by self-help organizations of people with disabilities.

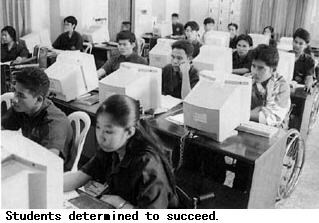

Training in computer and related fields is a successful means of expanding employment opportunities for people with disabilities in Thailand. In rural India, horticulture has opened up employment as well as self-employment opportunities for people with disabilities. Those two programmes are run by people with disabilities with full support from a church (Pattaya, Thailand) and a local community (Bangalore, India).

Case study 9: The Redemptorist Vocational Training School, Pattaya, Thailand

Case study 10: Horticulture as an employment opportunity for people with disabilities

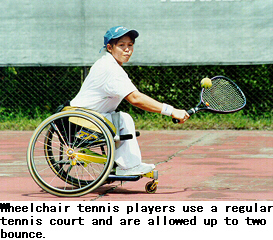

E. Development of sports and recreational activities

International sports events for people with disabilities have been a major stimulus for national Government to take drastic measures to improve national policies and programmes to develop abilities of people with disabilities. The Tokyo Paralympics in 1964 had a profound impact on many government officials, people working for disabled persons and the general public. They were shocked to note the significant differences, not only in athletic abilities between Western athletes and Japanese disabled athletes, but also in their appearance, self-confidence and their occupations. Most of the Japanese athletes who participated in the Tokyo Paralympics were hospital inmates. In contrast, the Western disabled athletes were living independently in their communities, held occupations and had families of their own. After the Paralympics, the Government of Japan embarked its services and programmes for people with disabilities.

Competitive sports are a tool to develop self-confidence and motivation for self-improvement of persons with disabilities. As the same token, organizing sports meets and tournaments will provide self-help organizations of disabled persons opportunities to develop the necessary skills and confidence in influencing national policies and programme in the area of sports. The following case-study describes a new development of self-help organizations of persons with disabilities in the area of sports in Thailand.

Case Study 11: Development of Thai disabled athletes through their own initiatives

F. Developinga network of self-help organizations through the Internet

Electronic communications infrastructure is developing rapidly in the ESCAP region. Computers are becoming more affordable by and accessible for many people, including people with disabilities. With appropriate training, computers immensely benefit people with disabilities in the areas of communication, daily living and employment.

In this connection, access to and the appropriate use of information is a key to the integration of people with disabilities into the mainstream society. Harnessing information technology can expand increasingly the horizons of people with disabilities. With such trends, disability may no longer be handicapping.

1. Rapid expansion of the Internet

The Internet is an amalgam of many different, independent networks, and it is rapidly growing. "Nobody can say precisely how many people are using the Internet today, but there are estimated to be more than three million host computers with as many as 30 million users around the world. The number of users is growing by 15 percent per month. Today 78 countries have full Internet access connections, and 146 countries can exchange e-mail, every 30 minutes, a new network signs on to the Internet."(23)

The Internet allows use of many tools, the most popular of which are e-mail and the World Wide Web (or "the Web"). E-mail is the main method of communication on the Internet. It allows messages or files to be sent to the accounts (addresses) of other people. These people can be on the same machine (server) as the sender or on machines across the world. A sender needs to know the exact address of a message recipient. E-mail provide a fast and reliable way to communicate. It is superior to telephone or fax in terms of cost, accuracy and convenience. The cost of e-mail messages is the same regardless of the distance messages travel.

The World-Wide Web is a vast collection of interconnected documents (hypertext), spanning the world. The advantages of hypertext is that in hypertext document, if one wants more information about a particular subject mentioned, one can select it to read in further detail. Today, there are many web sites in the Internet providing information on various topics, including disability-related issues. Through "search engines", one can find a vast amount of information which can be easily down-loaded onto one's computer.

The Internet can provide excellent opportunities for people with disabilities to communicate with others and collect information at their fingertips which is otherwise not easily available. To ensure that disabled people benefit, web sites need to be fully accessible by people with disabilities, in particular visually disabled people who cannot see graphics. As most of them have low incomes, disabled people should be provided with some types of subsidies for purchasing computer hardware and software, charge of Internet service and the cost of telephone calls. They should also receive adequate training on use of computer, and the use of e-mail and "surfing" the Internet. The Governments in the ESCAP region are recommended to make appropriate use of the Internet for the dissemination and retrieval of data concerning disability.(24)

The establishment of communication networks through the Internet among self-help organizations of people with disabilities in the ESCAP region may be soon a reality, as many organizations have already obtained computers, modems and telephone lines in their offices. They should advocate full access to the Internet by people with disbilities through ensuring accessible web sites by persons with various disabilities as well as guaranteeing their members' access to computer equipment and Internet services.

2. Telework

Teleworking is working at a distance from one's employer, either home, on the road, or at a locally based centre. Teleworkers use computers, telephones and faxes to keep in contact with one's employers or customers.(25)

Because of the recent rapid technological development, teleworking has become reality in many developed countries. It will soon be introduced to the developing countries of the ESCAP region. In order to ride on this trend, disabled people should be given priority in receiving training and be involved in teleworking communication centers, if such scheme is planned.

Teleworking can be ideal solution for those with difficulties in commuting to a work place. There are advantages for people with disabilities or for those with domestic or other commitments such as young children. Advantages include the following:

- (a) freedom from the problems and costs of commuting;

- (b) flexibility of working hours;

- (c) ability to fulfill domestic responsibilities.

Disadvantages include the following:

- (a) funds required to purchase equipment and suitable work area free from family interference;

- (b) isolation from other workers;

- (c) ability required to organize work well and maintain strict schedules.(26)

Teleworking is obviously not for all disabled persons. However, it will open up employment opportunities for qualified disabled persons.

G. Training in self-advocacy and empowerment

Advocacy for people with disabilities works to enhance, through collective action, their opportunities and decrease barriers in society. Thus, advocacy is an important activity of a self-help organization. However, many members have never had opportunities to voice their needs and to express how they should be met, due to lack of self-confidence, basic knowledge and skills to do advocacy. To be good advocates, members of self-help organizations need opportunities to learn to be assertive and to improve their skills in expressing themselves.

1. Definition of advocacy

Some definitions of advocacy are as follows:(27)

"Advocacy is a tool based on organized efforts and actions that uses the instruments of democracy to strengthen democratic processes. Such tools include election related work, lobbying, mass mobilization, forms of civil disobedience, negotiations and bargaining and court actions. These are meant to be illustrative actions. Advocacy should be open to invent other formal and informal actions. These actions are designed to persuade and influence those who hold governmental, political and economic power so that they will formulate, adopt and implement public policy in ways that benefit, strengthen and improve the lives of those with less conventional political power and fewer economic resources..." (Advocacy Institute, Washington, USA)

"Advocacy is a tool based on organized efforts and actions that uses the instruments of democracy to strengthen democratic processes. Such tools include election related work, lobbying, mass mobilization, forms of civil disobedience, negotiations and bargaining and court actions. These are meant to be illustrative actions. Advocacy should be open to invent other formal and informal actions. These actions are designed to persuade and influence those who hold governmental, political and economic power so that they will formulate, adopt and implement public policy in ways that benefit, strengthen and improve the lives of those with less conventional political power and fewer economic resources..." (Advocacy Institute, Washington, USA)-

-

- "Policy advocacy is a planned, organized and continued endeavour to influence policy decisions at various levels and their implementation for eradicating poverty, eliminating gender discrimination, establishing social justice and human rights, strengthening democratic process and promoting an environment- friendly sustainable development." (Proshika, Bangladesh)

2. Why self-advocacy?

People with disabilities are the poorest of the poor in many societies, and disability issues receive the least priority. This situation needs to be corrected. When advocacy is discussed among persons with disabilities, it is self-advocacy, advocacy by and for persons with disabilities. Self-advocacy is based on the notion that those who know best the needs of disabled people are disabled people themselves. Disabled people daily experience discrimination and prejudice because of their disability. For self-advocates, these become their source of energy for social change.

- "The contemporary role of persons with disabilities in advocacy and consumer involvement continues to develop toward self-direction, self-determination, and self-assertion of their special interests, citizenship and rights."(28)

Thus, key words for self-advocacy are "self-direction", "self-determination", "self-assertion", "citizenship", "rights", and "social change as the goal".

For people with disabilities, being a self-advocate means the following:

- (a) To make decisions and solve problems on their own;

-

- (b) To speak assertively for themselves;

-

- (c) To know their rights and responsibilities as citizens;

-

- (d) To make contribution to their community.(29)

Being a self-advocate is a process of empowerment. Through this process, people with disabilities can become self-determined, assertive, and contributing members of society. In this process, assertiveness is an important factor. Disabled people tend to respond in non-assertive or aggressive manner because they are generally expected to behave in such a manner. Thus, they should learn how to assert themselves.

Assertiveness means to:

- Stand up for what is best for you;

- Stand up for your rights;

- Make sure other people understand what you need and want;

- Openly and honestly express your opinions and feelings;

- Respect other people's rights and opinion;

- Listen to other people.

Assertive people feel good, honest and respected, and proud of themselves. Other people will see them as capable, able to make decisions, independent, adult, honest and appropriate.

Each individual with disability can be a self-advocate, but if self-advocates work collectively, it can make significant changes in the community. Thus, self-help groups or organizations can play a bigger role in advocating collectively the rights of people with disabilities. The following are advocacy strategies for self-help organizations of disabled persons:(30)

- (a) Help people with disabilities to openly and confidently acknowledge their needs;

-

- (b) Teach them how to influence the decision-making process in public and private organizations;

-

- (c) Guide them in identifying allies with whom they can make common cause.

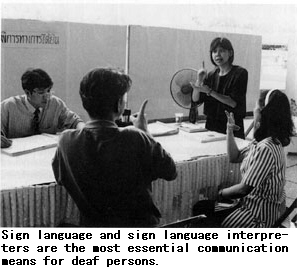

Acknowledging needs is not easy task. The needs may include curbcuts, ramps, accessible toilets for persons with a mobility impairment, interpreters for deaf people, or readers for blind people. Acknowledging them requires a willingness to stand up and be identified as someone who does have disability and have special needs. This step requires understanding of these needs as rights to live in the community.

The second step requires some sense of how the world works, of how public decisions be made, which many disabled people do not yet understand. The third step requires an understanding of how to create coalitions of diverse groups to harness their collective energy.

Case study 5:

Sanghams of village people with disabilities (13)

Background: Poverty and disability

Poverty is the root cause of disability in developing countries. Ninety per cent of people with disabilities in those countries are poor. Malnutrition, unclean drinking water and lack of immunization all contribute to preventable disabling conditions.

Structural-adjustment programmes of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have exacerbated these difficulties, by requiring the reduction of public expenditure and removal of subsidies. The former has made health care less accessible to the poor, and the latter contributes to malnutrition by increasing the price of essential commodities such as lentils (often the only source of protein for poor people) beyond their reach. The rationale for this approach is that wealth will be generated which will then "trickle down" to the poor, but there has not yet been a case in point to validate that argument.

Water is scarce in many rural areas of India. In many places, women must walk miles to obtain it. Some believe that poor people do not understand the need to boil water for drinking. More commonly, however, por families simply do not have more than two pots for cooking, let alone for storing, and fuel for cooking is not easy to come by. They are therefore unable to boil water to make it safe to drink.

Casual enquiries of many poor people show that they do not understand the value of immunization, because it has not been explained to them in a manner that they can understand. Those that do recognize its importance have often found attempts to get children immunized to be in vain; on the day they went to a clinic, the health worker did not show up or no vaccine was available. They cannot go again and again because most of them are daily wage labourers. Unfortunately, when poor countries typically spend more than three times as much on the defence as on health and education combined, this situation is unlikely to improve.

The census is an internationally accepted method to collect data. Yet in many poor countries, people with disabilities are excluded from the census as a matter of course. When they are not even counted in the statistics, planning for their inclusion in national development programmes at best is a token. Still, their numbers are great by any count. Conservative estimates state that 3 per cent of the world's population has disabilities; even if this figure is accepted (the World Health Organization estimates 7 per cent), it means that China has more than 30 million people with disabilities - more than the entire population of Australia. This many people deserve political clout and adequate provision in national plans.

The problem is that many people with disabilities have not organized to bring about change. Those who work with people with disabilities in poor communities have often heard them say "They call me lame because I am lame". Further reflection shows these responses indicate apathy, not acceptance of the situation. A deeper enquiry shows this apathy to be rooted in the human deprivation faced by disabled people. They are typically either neglected or over-protected, denying them opportunities for early childhood stimulation, play, companionship, education and gainful employment, let alone marriage. While the physical and security needs of disabled children and adults are met in some measure, their needs for love, belonging, self-esteem, recognition and self-actualization are not.

The lives of people with disabilities are given little value, as they have few opportunities either to be economically productive or to fulfill social functions - even though the material possibility exists for most of them to be as productive and functional as any other member of society.

Self-help organizations

Over the last decade, national-level organizations of people with disabilities have emerged in developing countries. Disabled Peoples' International has given impetus to this development. This is undoubtably a positive step towards promoting independence and self-advocacy.

However, the leadership of these organizations usually represents only a small minority of people with disabilities: those who have had access to education and good economic opportunities. They are largely from urban or semi-urban areas and the middle classes. While the value of these leaders' contribution is certainly significant, the resulting organization structure and ethos do not provide adequate mechanisms for a large portion of organization membership to participate in self-advocacy. Although the organizations are democratic and have mechanisms for participation in elections, a large proportion of their members do not know why they are members and what they are entitled to. As a result, many do not pay their subscription or membership fees. In the extreme case, such national associations can themselves become elitist, promoting the needs of only a select few of their constituency.

National self-help organizations in many countries are based on single disabilities. It is common for these organiztions to compete with each other for resources which are already scarce, and are often made more scarce by new government economic policies.

People with disabilities are dispersed throughout each country. The number of people with disabilities in any one community may be very small, with each of these people having a different disability. Seven people has been found to be an optimal number to form an organization of people with disabilities. When one can find seven people with disabilities in a community, it is unlikely that they will all have the same disability. Therefore, it is probably best to encourage people with all kinds of disabilities in any given community to come together and form a joint organization, to increase their collective strength and protect their rights. Their eventual presence in a national organization will ensure the representation of poor people with disabilities.

An NGO called Action on Disability and Development (ADD) was set up in the UK in 1985 to support people with disabilities to form their own organizations and to combat poverty. An indigenous NGO by the same name was set up in 1987 in India. Both organizations believe that only people with disabilities can bring about fundamental change in their own situation; no one else can do it for them. Therefore, both organizations promote self-help groups of disabled people in poor communities (known as sanghams in India), helping them to identify their own needs, assist them to prioritize and take action.

The sangham approach

"Sangham" means "association" in Indian language. As an association, a sangham has goals, rules and regulations. The goals include individual and group goals, which are set up cooperatively, not competitively.

ADD and ADD India have reached about 1,400 villages including about 5,000 men, women and children with every kind of disability. The sanghams they form are all cross-disability organizations, which is important because the issues of poverty and changing attitudes are common to all disability groups, and because the power of the poor is in their numbers. If disabled groups are divided by disability category, they will become weaker.

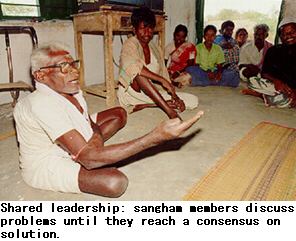

Sanghams practice shared leadership, in which problems are put forth to all members so that they can participate in solving them. They discuss problems until they reach a consensus among themselves for solutions. This is opposed to consultative leadership, in which a leader consults with other members but makes the final decisions himself or herself.

A sangham includes between 7 and 20 people with disabilities, a size that allows for shared leadership and meaningful participation. The group elects a president, secretary and treasurer, but members take turn to be office-bearers. One of them must be a woman. The sangham meets twice a month to discuss various matters, including education for children with disabilities, assistive devices, income generation, property, marriage, sexual abuse, drinking water and health. If necessary, they will meet with representatives of the local authorities for improvement of their situation.

Many sanghams undertake savings as an activity. Each member puts a small amount of savings into common coffers. Members can borrow with interest from this fund, either for emergency use or for capital for income generation. Sanghams are also active in village immunization campaigns; sangham members go to see families in the village to motivate them to have their children immunized.

Sanghams also deal with larger issues. Many sanghams join with other groups, such as women's and youth groups, in undertaking campaigns to address community needs such as drinking water, roads, or better health service delivery. Some sanghams have joined land struggles with other groups of poor people. By so doing, they begin to fulfill a social fuction in the community and get identity and recognition.

The sangham movement reached a milestone when 78 disabled people contested the panchayati raj (village local authority) elections in Andhra Pradesh and 31 of them won. They contested with a union of agricultural labourers promoted by Young Indian Project, an NGO. The union's membership consists of various sections of the poor, artisans, women, and people with disabilities. While each of these groups has its own self-help group at the village level, their representatives merge into a union at the district level. These unions now have a membership of more than 250,000 people, including people with disabilities. In total, the Union contested 7,000 seats, of which it won 5,000.

ADD India's other partners are also encouraging self-help groups of people with and without disabilities to make linkages for common and disability-specific struggles. People with disabilities are represented in the gram sabhas (village committee). People with disabilities are now running in local authority elections in programme areas influenced by ADD India.

Representatives of self-help groups of people with disabilities met on Human Rights Day in 1996. This is a fore-runner to disabled people forming their own federation to represent and protect the interests of poor rural people with disabilities. Encouraging linkages with other oppressed groups, at both the local and national levels, is the only way to get meaningful representation of poor people with disabilities in the decision-making of national disabled people's organizations and of the Government.

ADD has established a training programme for NGO personnel interested in helping with the formation of village sanghams. For more details, see Annex III.

Impact

In the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu in southern India, mainstream rural-development NGOs are encouraging about 5,000 people with different disabilities to organize themselves into about 380 self-help groups. The role of ADD India has been to influence them to undertake this work and to provide support for policy formulation, programme design, training, networking and follow-up. ADD India works in partnership with these NGOs over a period of two years, and takes on new NGOs thereafter. In the last ten years, ADD India has been able to influence about 22 NGOs to help organize people with disabilities. The NGOs find the funding for the work. ADD India has been one of the agencies instrumental in influencing the Ministry of Rural Development to allocate funds for organizing disabled people in rural areas.

The experience in Bangladesh and Cambodia

The situation in Bangladesh is very similar to that in India. The ADD programme in Bangladesh has adopted the Indian model of directly working with disabled people and also influencing mainstream rural-development NGOs to undertake organizational work of disabled people.

In Cambodia, ADD works directly with disabled people in two communities. Cambodian society is fragmented in the post-Khmer Rouge era. Enabling communities to address their health problems, and thus creating an environment of caring for each other, including disabled people, has laid a strong foundation for ADD's work. A similar process of caring and sharing among people with disabilities has enhanced their human development enough that they can reach out to the community. A main activity of the self-help organizations is thrift saving.

In one of the communities, drinking water is scarce. An international NGO digs wells for communities, provided the community bears a certain portion of the cost. The self-help group in one of these villages contacted the International NGO and learned aout this scheme. Then they approached the village chief to get the community contribution; they found out that he did not have any community money with him, but that he could raise it given some time. The self-help group gave him all its savings as an advance to the community. This is just one example of how much disabled people care for and share with one another and their community.

Difficulties encountered

The first problem encountered in the sangham movement is enabling people with disabilities to believe that they can do things for themselves and for others. Communities often do not see the value of organizational work and political education. They discourage disabled people from attending meetings, and sometimes even abuse development workers. Influencing NGOs is easier said than done, as they often see disability as a non-issue. Even after they begin work for disabled people, it takes a long time before that work takes its rightful priority. The important issue is to get disability onto the development agenda of NGOs and Governments. Once this is done, it will have its own momentum and dynamics to reach its rightful place, as has happened with women's issues.

The next ten years

Sanghams of people with disabilities will stay and the number of sanghams will grow. However, it is not certain what kind of ideology the movement will adopt. Many hope that it will adopt the view of disability as a poverty and human-rights issue. The more federations of sanghams are formed and the stronger the linkage between the sanghams and other disadvantaged groups become, the greater the impact that the sanghams will make on the lives of rural disabled persons - not only in south India, but in other parts of the world. However, cautions have to be taken when the sangham movement is to spread elsewhere. People often pay more attention to inputs and outputs than to the process of development work. The sangham work is process. It takes time and a certain methodology to produce good results. Unless people recognize this and take the time to learn and applying it, it will only produce mediocre work.

Contact details:

- Mr. B. Venkatesh

- c/o Centre for Education and Documentation

- No.7, III Phase

- Domlur II Stage,

- Bangalore 560071

- India

- Tel (res.): +91-80-545-1152

- (For message): +91-80-5543397

- Fax: (91-80) 5580357 Att: CED for Venkatesh

- E-mail: venky@ilban.ernet.in

Case study 6:

Independent-living centres in Japan (14)

The independent-living movement in the United States

The disability movement in the United States was strongly influenced by the American civil-rights movement, especially the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1972 Ed Roberts, a polio survivor who used a wheelchair equipped with a respirator, was about to graduate from the University of California at Berkeley. He had managed life at university by obtaining assistants for personal care and other necessary services in an accessible residence at the university hospital. However, these services were no longer available as soon as he graduated. Discussing their future, Roberts and his friends with disabilities decided to establish an independent-living (IL) centre in the community with the cooperation of their families and friends. The independent-living movement grew out of this first centre.(15)

Basic concepts of the IL movement

The founders of the IL movement proposed the following four key concepts as part of it:

- (a) People with disabilities should live in their own communities;

-

- (b) People with disabilities are neither patients to be cared for, children to be protected, nor gods to be worshiped;

-

- (c) People with disabilities themselves can identify what assistance is necessary and manage it;

-

- (d) People with disabilities are the victims of social prejudice, not of disabilities.

In the traditional medical model, people with disabilities were treated as defective models who were expected to reach the level of people without disabilities. Rehabilitation forced people with disabilities to get dressed by themselves without any assistance, no matter how much time it took. The IL philosophy, on the other hand, suggested that asking for help was not a shame and that it would not harm the self-reliance of people with disabilities. It regarded people making their own choices and decisions as the most important thing. Rehabilitation should be limited to the medical treatment required for a certain period of time, rather than controlling the entire lives of people with disabilities.

History of IL Centres in Japan

In Japan in the 1960s, the Blue Grass Movement (of people with cerebral palsy) centered on a struggle against discrimination. The movement insisted that disability was "one of the attributes of a person"; its philosophy was close to that of the IL movement.

Ed Roberts introduced the IL movement itself to Japan in 1981, the International Year of Disabled Persons. Judy Heumann and other disability activists also soon toured through Japan to elaborate the IL philosophy. These lectures generated enthusiasm everywhere they occurred. The main focs of the talks was on the philosophy, rather than the services, of IL centres.(16)

The first IL centre in Japan, the Human Care Association, was established in Hachioji, Tokyo in June 1986, through activities of the Wakakoma Center in Hachioji city. Established 20 years ago, the Wakakoma Center was a day-activity centre managed by and for people with extensive disabilities. It later gave way to the First Wakakoma Center, the Second Wakakoma Center, and the Mokuba Workshop. These were created according to the specific needs and activities of people with disabilities in Hachioji: day-activity centres for young people with extensive disabilities, day-care centres for people with multiple disabilities and sheltered workshops.

As the number of people requesting personal assistance service at these centres increased, it became difficult to find assistants on an individual basis. This need led to the idea of establishing an organization to provide dispatch services for personal assistance.

The purpose of IL centres in Japan

People receiving the services of the Human Care Association have many different types of disabilities. One of the Association's objectives is to be a core force for social change beyond the IL movement. The Japanese disability movement has so far been divided by type of disability, and clustered into local community groups or small circles. The Human Care Association, on the other hand, is a self-help organization of qualified individuals with different types of disabilities in different areas. The Japanese disability movement previously focused on protesting, demanding and advocating. People with disabilities had not aimed to provide services by and for themselves. The formation of the Association helped make society realize that people with disabilities could do so.

People with extensive disabilities are often put in the custody of their parents at home and their teachers at school(17), leading them to be dependent and lack basic living skills such as time management or even self-expression. Aiming to remedy such a situation, the IL centre in Japan emphasizes two major programmes: the provision of personal-assistance services and the organization of independent living skill training programmes.

Programmes of the Association

As a model for IL centres in Japan, the Human Care Association established a principle that IL skill training and personal-assistance services were essential. Many founding members of the Association had been involved in managing the Wakakoma Center, one of the two disability activist groups in the 1970s, and were therefore aware of the situation and basic needs of people with extensive disabilities. Many of them had been home-bound or institutionalized since early days of their life and had had little social experience.

If IL centres provided only personal-assistance services, their users might become dependent on the assistants and continue living alone without knowing the importance of making choices and decisions of their own. On the other hand, if the centres only organized IL skill training with no personal-assistance services, users might acquire the IL skills and philosophy without seeing any changes result in their lives.

a. IL skill training

The IL skill training programme was started at the Wakakoma Center. People with disabilities attending the programme had to learn how to build human relationship, how to solve own problems and claims, how to manage their money and other practical skills for IL, after previously being stuck at home or in institutions.

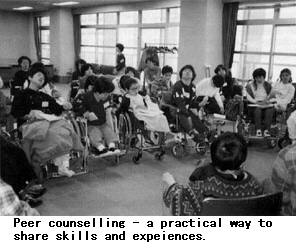

Peer counselors, who have disabilities and are already living indepndent lives, lead the programmes and give support to participants. Each programme consists of 12 regular sessions, one session per week, with an average of six to eight people with disabilities participating in each session.

The programme teaches the following skills and topics:(18)

- (a) Goal setting;

- (b) Identity establishment;

- (c) Health and medical care;

- (d) Communication with attendants;

- (e) Human relationships;

- (f) Management of money;

- (g) Management of time;

- (h) Shopping, meal planning and cooking;

- (i) Sexuality;

- (j) Utilization of social resources.

In each session, the peer counselor acts as programme leader, using such methods as group discussion, role-playing, and field trips. The association formulated IL skill-training modules and field-tested them for three years with the people with disabilities in Wakakoma Center and other self-help organizations. The modules were accepted and published as a textbook entitled Manual for Independent Living Program in 1989. This programme is now adopted by other local IL centres in Japan.

People in the United States have experimented with various types of IL skill training. The programme in Japan is different from these because of cultural differences. For example, it was difficult to show the importance of assertiveness to Japanese people with disabilities, a problem shared in other East Asian countries. As a result, the Japanese IL skill-training programme has proved useful in those countries.(19)

In 1994, the Association published the English version of the Independent Living Skill Training Manual and organized the First Asia-Pacific IL Workshop in the Philippines, with the Stockholm Cooperative for Independent Living. It has also trained the Thai and Filipino participants of the annual IL Study Program in Japan, jointly organized by the Catholic Association of Disabled Persons and the Asia Disability Institute since 1992. It is preparing to organize a workshop on IL in Seoul, Republic of Korea in 1998, including the translation of the manual into Korean.

b. Peer counselling

The acquisition of IL skills for people with disabilities is a difficult task and takes time. They are typically used to people saying "You cannot do anything because you are disabled", "Never hope to get married" or "Don't go out because you are a shame to the family" since their childhood. This discouragement damages their confidence and dignity, making counselling a necessity for their self-esteem. Counsellors should also have disabilities, and should treat service users as equals - as peers, not clients.

The term "peer" was introduced to counselling in the 1970s by Alcoholics Anonymous in the United States. People with disabilities in Japan refer to their counselling as peer counselling. The term emphasizes the equal relationship between counsellors and service users. IL centres in the United States also provide the same type of counseling programme.

In 1988 the first intensive course for peer counsellors was organized Now, the counsellors have themselves become leaders of the IL movement throughout Japan. The term "peer counselor" spread among mass media and social services. The National Government has adopted the concept of peer counselling in programmes for people with developmental disabilities, and more recently for people with locomotor disabilities.

c. Personal-assistance service

The personal-assistance service helps people with disabilities live independently by giving referrals and sending personal assistants to those who need help with daily activities such as moving into and out of bed, taking a bath, going to the toilet, cooking and cleaning. The service is performed based on user needs. People with any sort of disabilities are welcome to use it (including older people, pregnant women, or people with temporary disabilities such as broken bones).

The service is provided on a commercial basis. Users pay personal assistants a fare between 1,000 and 1,200 yen (US$ 8-9) per hour. This indicates that users are to be treated as employers; when the Government provided these services free of charge, volunteers serving as caregivers often acted like superiors of the people they were supposed to be helping.

The personal assistants can work at any time. The policy specifies that the hours of service provision are generally from 7 am to 11 pm, but people who face difficulty at night or early in the morning may use personal-assistance services at any time. 50 per cent of the 400 registered personal assistants are homemakers; 30 per cent are students; and 20 per cent are freelance workers and/or retired people. Most commonly, students work at night, retired people in the early morning, and homemakers in the day time.

When a user requests personal-assistance service, the coordinator of an IL centre makes a home visit to interview that user about his or her specific needs. The coordinator also gives the user information on community resources, including public home-helper services, housing referrals and modifications, and available self-help tools and devices, so that the user can make the best use of social resources to achieve IL. Then, the centre selects and refers a personal assistant who can best meet the need of the user.

The personal-assistance service is based on the rights of the user as a consumer. Therefore, before making contract with their personal assistants, users may turn down personal assistants they find unacceptable up to three times. If a user wants to go out on an extremely cold day, an assistant has no right to stop this decision and should support it; the responsibility is the user's. Freedom and responsibility are the bases of IL.

The Japan Council of Independent Living Centers (JIL)

Since 1989, new IL centres have been established across Japan. The majority of them are modelled on the Human Care Association; some of those who started these centres worked or were trained at the Association. The basic programmes are available at the IL centres of Machida Human Network, Hands Setagaya, and CIL Tachikawa. Other organizations such as Sapporo Ichigokai, AJU Independent House and Shizuoka IL Center of Disabled Persons, share similar services and programmes.

In order to share skills and information, twelve IL centres around the country agreed to form the Japan Council of Independent Living Centers (JIL). They established it on 22 November 1991 after the preparatory meeting for establishment late in 1990. The agreement of JIL, which mostly follows that of the American National Council of Independent Living, specifies the following:

- (a) 51 per cent of the board members should be people with disabilities;

-

- (b) A person responsible for managment should have a disability;

-

- (c) IL centres should provide their services to people with any kind of disabilities;

-

-

(d) In addition to the two basic services of information referral and human-rights advocacy, centres should provide the following servics;

- IL programmes;

- peer counselling;

- personal-assistance services;

- housing referral and modification.

IL centres are admitted as members if they provide at least two of the aforementioned four services; if they provide one, they are designated as associate members. Groups and/or organizations that intend to start services and become IL centres later are appointed as future members.

JIL has sub-committees on the following four topics:

- (a) IL programs and peer counselling;

-

- (b) policy making;

-

- (c) management of IL centres and other services;

-

- (d) disability rights advocacy.

A seminar for the presidents and/or directors of IL centres is held annually, in order to develop their management skills. A peer counsellor training programme and IL skill trainer programme are also organized every year in various parts of Japan. In 1997, 74 IL centres in Japan are registered as members of JIL. Approximately ten IL centres are newly established every year.

Future plan for IL centres

IL centres in Japan have developed for eleven years. As organizations providing services to, by and for people with disabilities, IL centres have become more widely accepted among communities and governments. Most of the officials in national and local governments now know what IL centres are. Last year, six IL centres were selected to operate the Community Service for Persons with Disabilities in Municipalities, one of the major programmes that the Governmental Plan for Persons with Disabilities initiated in 1996. JIL is working to increase that number.

Since the IL concept is very different from the traditional institutional approach, existing institutions will likely begin to change as IL centres develop and provide community services. Staff who try to meet service users' needs at nursing homes or disabled people's institutions are likely to find the philosophy and services of IL more suitable.

The most important objective of IL centres now is to convert institutional social welfare servies to services based on users' needs. Present public services are limited to people aged 65 or over, or people whose disabilities are classified in six grades according to their severity. This current situation results in segregation and overprotection, while need-based social services enable people with disabilities to have what they want without any hesitation. These are the services that IL centres should provide.

The next objective is to make the national Government legislate the system of IL centres, reforming the Japanese system for social foundation itself in order to realize this objective. An organization needs the Government's authorization to get government grants and funds regularly. It is, however, currently a complicated and difficult process for a foundation to get the authorization. As a result, Parliament has been discussing the enactment of a new law for non-profit organizations.

It is important for IL centres to become more efficient and supportive. JIL and its regional bodies, such as TIL (the Tokyo Council on Independent Living Centers), are responsible for enforcing this objective.

Note that the IL approach does not deny the importance of rehabilitation specialists or their specialties at all. Rather, IL centres expect that professionals are of great help in giving the highest priority to the needs of people with disabilities.

Contact details:

- Mr. Shoji Nakanishi

- Director

- Human Care Association

- Part 1-1F,

- 4-1-14 Myojin-cho, Hachioji City,

- Tokyo, 192 Japan

- Tel: (81-426)46-4877

- Fax: (81-426)46-4876

- E-mail: YHY02306@niftyserve.or.jp

Case study 7:

The Campaign to Send Wheelchairs to Asian Disabled Persons

In 1992, eleven Japanese organizations of people with disabilities, along with the Asahi Shimbun (newspaper) Social Welfare Organization, collaborated with organizations of people with disabilities in Asian developing countries to initiate the Campaign to Send Wheelchairs to Asian Disabled Persons. Each Japanese organization collected used wheelchairs and refurbished them, then dispatched them overseas.

So far, the campaign has dispatched 630 wheelchairs to organizations run by and for people with disabilities in Bangladesh, the Philippines and Thailand. The recipient organizations have then distributed the donated wheelchairs to people with disabilities based on a careful evaluation of their economic condition and aspirations for work and independence.

Most wheelchairs made in Thailand have been heavy (about 30 kg) and built for use in a hospital or other institution. These heavy wheelchairs have prevented many Thais with disabilities from participating in activities outside institutions. The Japanese wheelchairs, by contrast, are made from stainless steel or aluminum alloy, and are thus lightweight, foldable and compact. Although previously used, they have become popular among people with disabilities who want to be more independent.

The project also started to train technicians with disabilities in wheelchair repair so that the donated wheelchairs can be repaired in Thailand when broken, rather than being sent back to Japan. In the early stage of the project, two Thais with disabilities were sent to be trained for one month in Japan. Five more training workshops were organized later in Thailand, along with one in Bangladesh and one in the Philippines, with Japanese disabled instructors dispatched to conduct training. In January and February 1997, 23 people with disabilities participated in a ten-day training workshop organized in Thailand. Two of these people came from Bangladesh, two from the Lao People's Democratic Republic, two from the Philippines and 14 from Thailand. Participants in the workshop learned how to produce wheelchairs as well as repair them, and all took home wheelchairs they had designed.

According to Topong Kulkanchit, past President of the Association of the Physically Handicapped of Thailand (APHT), which hosted the Thai training workshops: "A wheelchair is the essential mobility device for people with mobility impairments. Without it, disabled people cannot achieve full participation in the community. Wheelchair production also can be a good income generating activity for disabled persons, and could be their steady occupation. We would like to share with other Asian friends the knowledge and experience that Thai disabled persons have gained through this project."

In Thailand, the APHT Wheelchair Workshop was established in 1993; it now employs seven male workers with disabilities and their wives. It produces average 30 light-weight wheelchairs per month, including sports wheelchairs.

In the Philippines, the wheelchair production facility in Tahanang Walang Hagdanan (House with No Steps) has improved its production capacity because of the support from this project. After the last workshop in Bacolod city, organized under the project, the Bacolod Association of Disabled Persons plans to establish a wheelchair production factory with support from the Bacolod city government.

Contact details:

- Ashahi Shimbun Social Welfare Organization

- Ashahi Shimbun Newspaper

- Osaka Headquarters

- 2-banch, 1-chome, Nakajima,

- Kita-ku, Osaka City 530-11

- Japan

- Fax: (81-6) 231-3004

- Association of the Physically Handicapped of Thailand

- 73/7-8 Soi Tivanond 8, Tivanond Road, Taladkwan, Muan,

- Nonthaburi 11000 Thailand

- Tel: (66-2) 951-0567

- Fax: (662) 951-0569

Case study 8:

A university-level Thai Sign Language certificate programme (20)

In the 1991 publication Self-Help Organizations of Disabled Persons (United Nations publication ST/ESCAP/1087), The National Association of the Deaf in Thailand (NADT) listed two short-term goals related to Thai Sign Language: more sign-language courses for hearing people, and a Thai Sign Language interpreter training programme. These goals are easy to understand, but less easy to achieve. Reaching the goals requires highly technical academic expertise in such areas as sign-language linguistics, second-language acquisition, second-language teaching methodology, curriculum development, materials development, theories of translation and interpretation, and methods of evaluating translation and interpretation.

While most NADT members are fluent users of Thai Sign Language, only a handful have had access to university education; no deaf person in Thailand has received formal university-level training in sign language linguistics and/or sign language teaching. So, on its own, NADT did not have and could not acquire the necessary academic knowledge and technical skills to teach Thai Sign Language professionally or to train professional Thai Sign Language interpreters. NADT decided to form a partnership with the institutions that could provide it with the skills it needed: Gallaudet University and Ratchasuda College.

Gallaudet University, established in 1864 by an act of the United States Congress with the approval of American President Abraham Lincoln, is the world's first liberal-arts university for deaf people. It has the world's largest library on deafness and considerable expertise in the theory of sign-language teaching and interpretation.

Ratchasuda College was established in 1992, as the result of many years of discussion and planning by HRH Princess Sirindhorn and the formulation of a new law in Thailand to aid people with disabilities. It is the first and only institution in Southeast Asia dedicated to providing tertiary education to deaf people, blind people, and people with locomotor disabilities. In 1996, Ratchasuda hired a foreign sign-language linguist and a foreign deaf-studies ethnographer, to begin systematic research on Thai Sign Language grammar and on deaf culture in Thai society. Since 1996, the sign-language linguist and the ethnographer have been collaborating on research projects on an informal basis with NADT.

NADT formalized its partnership with Gallaudet and Ratchasuda in 1997, with an agreement to collaborate on a project known as the Thailand World Deaf Leadership (WDL) project. The collaboration with Gallaudet will ensure the Thai institutions' access to foreig expertise; the collaboration with Ratchasuda will ensure long-term sustainability and acceptability of the programme in Thailand.

The Thailand WDL project has three major objectives related to sign language teaching, each discussed in turn in this paper:

- (a) Establishment of a university-level programme to train deaf people as professional teachers of Thai Sign Language;

-

- (b) Development of a standard curriculum for teaching Thai Sign Language and of teaching materials for courses in Thai Sign Language;

-

- (c) Establishment of university-level courses in Thai Sign Language that will be taught by graduates of the training programme.

Objective 1. Establishment of a university-level programme to train deaf people as professional teachers of Thai Sign Language.

The establishment of a university-level programme to train professional Thai Sign Language teachers should accomplish several goals. First, it should provide deaf people with the expertise to teach Thai Sign Language effectively and help train future interpreters. Second, it should provide deaf Thai Sign Language teachers with university credentials, so that Thai society will recognize their qualifications. Third, it should ensure that deaf people can control the teaching of their own language. Finally, it can expand educational and employment opportunities for deaf people in Thailand by focusing on issues that are of importance to the Thai deaf community.

In the context of the NADT-Gallaudet-Ratchasuda WDL program, the completion of Objective 1 will result in at least seven deaf graduates (members of NADT) per year who have been professionally trained and certified as teachers of Thai Sign Language. To accomplish this objective, NADT needed to work with Gallaudet and Ratchasuda to complete four steps, labelled here as 1a) through 1d).

1a) Designing a series of courses that form a cohesive programme.

Very few Thai deaf people have had any college experience, Ratchasuda does not currently have enough faculty who know Thai Sign Language to teach undergraduate general-education courses, and Thailand has no professionally trained sign-language interpreters to interpret general-education courses. For these reasons, NADT, Gallaudet and Ratchasuda agreed to start the training programme as an undergraduate certificate programme, which will eventually be transformed into a B.A. degree programme. (A similar approach was used successfully in the early stages of nursing education for hearing people in Thailand.)

NADT, Gallaudet, and Ratchasuda decided to use the core requirements for the B.A. degree in sign language teaching at Gallaudet as a model for the requirements of the undergraduate certificate programme in Thai Sign Language teaching methodology at Ratchasuda. See Annex IV for a description of the courses available in the programme.

1b) Proposal of the training programme to the Royal Thai Government for recognition.

NADT and Ratchasuda are preparing a formal proposal, according to officially recommended guidelines, that will allow programme graduates to be appointed as teachers of Thai Sign Language (as a second language) in the Royal Thai Government Civil Service System. They have contacted the appropriate Royal Thai Government offices for approval. Since all graduates of the programme will be deaf, deaf people will be the official teachers of Thai Sign Language in Thailand. This fact ensures that deaf people in Thailand can keep control over their own language and programmes related to it.

1c) Selection of Thai deaf people who will study in the programme.

The selection procedures agreed upon by NADT, Gallaudet, and Ratchasuda ensure maximum input from deaf members of NADT. Potential students for this programme must be all of the following:

- (a) at least 18 years old;

-

- (b) deaf;

-

- (c) a member of, or willing to become a member of, the National Association of the Deaf in Thailand;

-

- (d) highly fluent (with native or native-like proficiency) in Thai Sign Language;

-

- (e) extensively knowledgeable about, and participating in, a deaf community in Thailand;

-

- (f) committed demonstrably to a career in sign language teaching and/or research.

In addition to these six requirements, a student must have completed a certain level of education to become a civil servant in the Royal Thai Government. Normally, the minimum education levels are M-6 (completion of secondary school) for people 18 to 25 years of age and M-3 (completion of 3 years past primary school) for people over the age of 25.

Students who do not meet the educational requirement can still study in the programme for employment as teachers of Thai Sign Language outside the Royal Thai Civil Service System. Under a special initiative from the Royal Thai Government and Ratchasuda College, students entering the programme with less than an M-6 education will be given the opportunity to complete M-6 through supplemental special education classes at Ratchasuda while they are studying for the certificate programme. However, students in the certificate programme will not be forced to complete M-6 before or during their studies for the certificate.

Potential students for this programme will be located through NADT, the four regional associations of deaf people in Thailand, schools for deaf people, and other organizations, institutions, and individuals working with deaf people in Thailand. Applicants to the programme must perform the following:

- (a) complete an application form (including three letters of recommendation);

-

- (b) prepare a written or videotaped statement of why they wish to enter the programme and what they plan to do upon its completion;

-

- (c) pass a Thai Sign Language proficiency examination jointly administered by Ratchasuda faculty and NADT;

-

- (d) be accepted for admission by an ad hoc Admissions Committee at Ratchasuda, at least half of whose members must be deaf.

From seven to ten students will be accepted each year, and between five and seven of these will likely receive full financial support for the duration of the certificate programme. At least one stipend per year will be reserved for female students. All other fellowships will be open equally to men and women. (The Canadian International Development Agency's Women's Initiative Fund in Thailand has agree to support fellowships for two Deaf women for the first class of students.)

1d) Selection of faculty members at Gallaudet to teach courses.

The first semester of the Thai academic year overlaps with summer vacation in the United States academic year (May-August). Each year during a portion of this period, Gallaudet University will send deaf university lecturers or professors of sign language instruction, and a sign language interpreter for the deaf instructors, to Ratchasuda College. They will collaborate with Ratchasuda faculty in teaching courses on the theory and methods of sign-language instruction, and in supervising practicum courses. Gallaudet will recommend faculty members, although the final selection of visiting faculty members will be made jointly by Ratchasuda and NADT.

Gallaudet faculty will teach general information about theory and methods, and Ratchasuda faculty will relate this material to Thai Sign Language. Ratchasuda faculty, in consultation with NADT, will develop and teach courses related to the structure of Thai Sign Language, instead of existing Gallaudet courses in the structure of American Sign Language.

Objective 2. Development of a standard curriculum for teaching Thai Sign Language and of teaching materials for courses in Thai Sign Language.

The development of a standard curriculum and teaching materials should accomplish three goals. First, it should provide teachers of Thai Sign Language with a high-quality curriculum and high-quality teaching materials. Second, it should provide NADT members with the skills necessary to continue developing Thai Sign Language teaching materials that NADT can market. Third, it should ensure that NADT will have extensive input into the development of curriculum and teaching materials for Thai Sign Language.

The completion of Objective 2 will result in a standard curriculum for a three-to-four-year teaching programme in Thai Sign Language, with a textbook and videotaped materials for each of three university courses in Thai Sign Language, one each at anintroductory, intermediate and advanced level.

To accomplish Objective 2, Gallaudet and Ratchasuda faculty will work with NADT in three ways, labelled 2a), 2b), and 2c).

2a) Teaching theory and practicum courses in curriculum and materials development.

Students in the certificate programme are required to take one theory course and two practicum courses in curriculum and materials development related to sign language teaching. The theory course will teach students about the theory of curriculum and materials development, about previously developed curricula for teaching various sign languages, and about previously developed textbooks and other materials for teaching various sign languages. In the practicum courses, students will work with faculty on applying this theoretical knowledge to developing a standard curriculum and textbooks for a university-level Thai Sign Language programme. This two-to-four-year programme will teach Thai Sign Language as a second language at the university level.

2b) Conducting and supervising research on the development of a standard curriculum, textbooks and other materials

In addition to the certificate program's courses in curriculum development, Gallaudet and Ratchasuda faculty will collaborate on externally funded research projects to develop a standard curriculum and textbooks for a university-level Thai Sign Language second-language programme. Students and graduates of the programme will be employed as research assistants and/or associates in these research projects.

2c) Producing written and videotaped versions of the curriculum, textbooks, and supplementary teaching materials.

At the end of each year, the latest version of the curriculum, textbooks, and other teaching materials will be written in Thai and English, and will also be videotaped in Thai Sign Language for distribution in Thailand and in other countries.

Objective 3. Establishment of university-level courses in Thai Sign Language that will be taught by graduates of the training programme.

Objective 3 is to produce three university courses in Thai Sign Language, one at each of the introductory, intermediate and advanced levels. Ratchasuda College will hire graduates of the programme to teach these courses for university credit. NADT will also hire graduates of the programme, to staff its own sign language teaching programme.

To accomplish Objective 3, NADT will collaborate with faculty from Gallaudet and Ratchasuda to do the following:

- (a) examine the existing bibliographies and syllabi for American Sign Language courses already offered in the United States and for courses on other sign languages already offered in other countries;

-

- (b) synthesize the information from these existing bibliographies and syllabi into a bibliography and syllabus appropriate for Thailand;

-

- (c) add information obtained from the research in Thailand on Thai Sign Language to this proposed bibliography and syllabus;

-

- (d) have graduates from the certificate programme teach and test experimental versions of the course at Ratchasuda and NADT.

Features necessary for sign-language teacher training programmes

Not only does the project provide the training necessary for NADT members to become professional teachers of Thai Sign Language, it also provides deaf people with university credentials that certify them and them alone as the official teachers of Thai Sign Language. Also, built into the training programme is a curriculum and materials development component that assures NADT will have access to and control over Thai Sign Language teaching materials. Finally, by hiring graduates of the programme to teach at Ratchasuda, NADT is assured input into and quality control over the College's Thai Sign Language programs. No other national association of deaf people in the Asia-Pacific region has such input and quality control at present. For these reasons, other national associations of deaf people may wish to emulate aspects of the Thailand WDL project in their own countries. Should they wish to develop similar sign-language teacher training programmes, they must consider three factors, each discussed below:

- (a) the preparatory sign-language research required as a foundation;

-

- (b) the planning necessary to start such a programme;

-

- (c) the human, managerial, and financial resources necessary to ensure the programme's success.

Preparatory sign language researc

Three basic types of formal linguistic research must be undertaken before a sign language teacher training programme can be attempted. The first type of research is a language survey to determine how many sign languages exist in the country, and how closely these languages are related. This type of survey should be carried out by a trained sign-language linguist working in cooperation with a national association of deaf people, or with local associations of deaf people if there is no national association. A typical sign-language survey might take from three months to a year to complete. Results will vary from country to country; for example, recent research shows that deaf people under the age of 50 in urban areas of Thailand use only one sign language, while, in urban areas of Viet Nam, they use at least three closely related sign languages, and perhaps more. Because of such differences, sign-language research and sign-language teacher training programmes must be developed on a country-by-country basis, tailored to fit the local situation.

In the second type of research, a trained sign-language linguist works with a national association or local associations of deaf people to create dictionaries for each of the country's sign languages. A team of five to ten deaf people working with an outside sign-language linguist and a local linguist can often finish a sign-language dictionary in one or two years. The outside sign- language linguist normally needs to be present for at least two to three months a year for such a project.

After the dictionary work is well underway, the third type of research can begin: a reference grammar of the sign language(s). Writing a reference grammar is a highly technical project, but is essential for teaching. No one can learn a language from a dictionary alone; one must have information on structuring words or signs into sentences. A team of the size mentioned for the dictionary can probably complete a reference grammar in two to three years, with the outside sign-language linguist present for four to six months a year.

Fortunately, NADT had previously worked with other organizations on preparatory sign language research, and therefore had the critical linguistic resources necessary for the teacher training project: a linguistically adequate dictionary of Thai Sign Language and an ongoing cooperative research project on the grammar of Thai Sign Language with a sign-language linguist.

Planning

Careful planning is necessary to establish a sign-language teacher training programme. The first step is to locate potential partners for the project: people who know about deaf people, sign language research and sign language teaching, and who are willing to work with associations of deaf people in the region where those associations are located. NADT selected Gallaudet because of its long-standing reputation as a university for deaf people and its relatively large number of deaf professors with M.A. and Ph.D. degrees. These professors can serve as teachers as well as academic role models for Thai deaf people who want to become teachers of Thai Sign Language. NADT selected Ratchasuda because it was dedicated to providing university education to deaf people in Asia (especially South-East Asia), was located in Thailand and could offer credentials that would be accepted in Thailand, and already had an informal working relationship with NADT in the sign-language research programme.

The second step in the planning process is to contact the potential partner organization(s) and set up a site visit of partner-organization representatives. In May 1997, NADT invited representatives from Gallaudet and Ratchasuda for a three-week site visit, during which it held daily activities related to the project. By the end of the site visit, NADT and representatives of Gallaudet and Ratchasuda had agreed on the objectives, a work pla and schedule for accomplishing the objectives, an estimation of costs necessary to complete the project, and possible sources of outside funding

After the site visit was completed, NADT stayed in contact with the partner organizations and helped in writing a proposal. Since NADT and its partners approved the proposal, NADT has worked with Gallaudet and Ratchasuda to find the human, managerial, and financial resources necessary to ensure the success of the sign language teacher training project.

Human, managerial, and financial resources

NADT needed to have the following human resources available within its own organization for the project:

- (a) Thai Sign Language-(spoken) Thai interpreter(s) for 24 to 40 hours a week;

-

- (b) deaf staff member(s) to work for 8 to 16 hours a week on community education, outreach, and publicity related to the project;

-

- (c) staff member(s) who know Thai, Thai Sign Language and some English for 32 to 40 hours a week to work as liaisons with Gallaudet and Ratchasuda on project administration, scheduling, correspondence, etc.;

-

- (d) at least seven deaf adult members of NADT each year who can study full-time for 18 months for the certificate (total of at least 35 Deaf people over five years);

-

- (e) an accountant who can write financial reports for the grant;

-

- (f) an overall administrator for the project.

It also needed to have contact with other organizations who could provide the following available outside resources for the project:

- (a) foreign deaf professors of Sign Language Teaching Methodology (NADT obtained them from Gallaudet);

-

- (b) foreign spoken-to-sign-language interpreters for the foreign professors (Gallaudet);

-

- (c) a Thai-English spoken language interpreter (Ratchasuda);

-

- (d) an expert sign-language linguist (Ratchasuda);

-

- (e) a local linguist interested in learning about sign-language linguistics (Ratchasuda);

-

- (f) Thai notetakers (Ratchasuda);

-

- (g) a video documenter to record the lectures and practicum courses for future use (Ratchasuda).

To obtain the necessary managerial skills, NADT has had to do the following:

- (a) organize local travel and accommodations for Gallaudet faculty who came on the site visit;

-

- (b) organize local and regional meetings for Gallaudet faculty to meet with deaf people throughout Thailand;

-

- (c) help set academic and funding priorities for the project;

-

- (d) assist in forming a Thai Sign Language evaluation committee for the project;

-

- (e) assist in forming a committee to screen applications for admission into the teacher training programme;

-

- (f) assist in forming an advisory committee with Ratchasuda faculty and representatives from Thai schools and government agencies;

-

- (g) arrange all publicity and outreach for this programme in the Thai deaf community;

-

- (h) decide on a budget for NADT expenses for the project;

-

- (i) manage the budget for the project in a separate financial account and make budget reports to organizations contributing money.

NADT has also had to work with Gallaudet and Ratchasuda to locate the financial resources needed for this project. The estimated costs for this project are from US$ 40,000 to 50,000 for each year, with about half of this money paying the expense of bringing Gallaudet faculty to teach in Thailand and paying three sets of interpreters (American Sign Language-English, English-spoken Thai, and Thai-Thai Sign Language).