Impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake on Persons with Disabilities and Support Activities

- Through Efforts by the JDF Miyagi Support Center -

Hiroshi Ono

Former Secretary General, JDF Miyagi Support Center

Introduction

“Tsunami tendenko” is a sad precept that has been passed down in the Tohoku region. The “ko” at the end is typical of the Tohoku dialect, such as in “yomekko” (from yome [wife]) and “umakko” (from uma [horse]). “Tsunami tenden” means that when a tsunami hits, one should not worry about one's parents or siblings but immediately flee to the nearest high ground. This precept is how people who live in the Sanriku area, which has been hit by tsunamis several times since the Edo Period (1603-1868), have been taught to flee to safety when a tsunami hits; and considering the short time from when the Great East Japan Earthquake hit to when the tsunami arrived, it is a very instructive escape method.

However, what should people with disabilities and the elderly, who cannot quickly flee on their own - in other words, vulnerable people in the case of an earthquake - do?

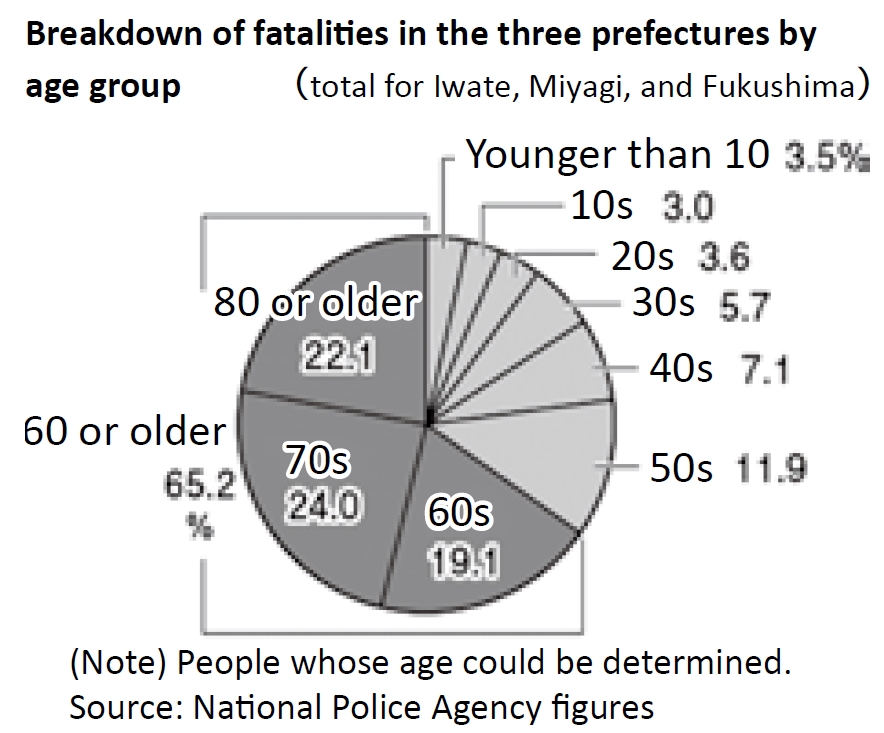

For the three Tohoku prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima, a breakdown of fatalities due to the Great East Japan Earthquake by age group reveals that 65.2% of fatalities were sixty or older, and those seventy or older accounted for 46% of all fatalities (based on National Police Agency statistics as of April 2011). These elderly victims include many persons with disabilities, and if one also considers non-elderly persons with disabilities and children, the number of vulnerable people in the case of an earthquake who cannot flee on their own is quite large.

Breakdown of fatalities in the three prefectures by age group

(total for Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima)

(Text)

(Text)

1. Impact of the earthquake on persons with disabilities in Miyagi

(1) Information on the impact of the earthquake on persons with disabilities finally released one year after the disaster

As of December 26, 2012, one year and nine months after the earthquake, 15,879 people died because of the disaster and 2,712 are still missing (figures released by the National Police Agency). In Miyagi, 9,534 people perished, and the whereabouts of 1,324 are unknown.

At the regular discussion held between JDF Miyagi Support Center (referred to below simply as the Miyagi Support Center) and Miyagi Prefecture in March 2012, it became clear for the first time that 1,104 persons with disabilities had died in the disaster. For municipalities that had confirmed the number of persons with disabilities who had died in the disaster, we compared the mortality rate for all residents and the mortality rate of persons with disabilities. As a result, we determined that the mortality rate for persons with disabilities was about 2.5 times greater than that for all residents. For Sendai-shi, there was no major difference in the figures for the overall city and those for the three coastal wards. It can be assumed, however, that the mortality rate for persons with a shogaishatecho (certificate for persons with disabilities) was even greater because the figure includes people with multiple certificates. Furthermore, the number of fatalities include not only those who died as a direct result of the earthquake but also those whose death was related to the disaster. The number of fatalities for all residents is the figure as of September 2012 while that for persons with disabilities is as of February 2012. Therefore, the number of persons with disabilities who died is surely greater than 1,104.

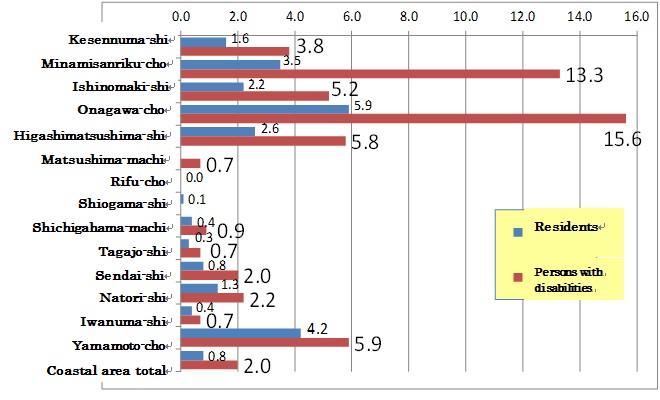

Comparing mortality rates by municipality reveals that the mortality rate for persons with disabilities is greatest in Onagawa-cho, at 15.57%. About one in every six persons with disabilities died in that city. Onagawa-cho is followed by Minamisanriku-cho with a mortality rate of 13.26%; Yamamoto-cho, 5.92%; Higashimatsushima-shi, 5.84%; and Ishinomaki-shi, 5.16%.

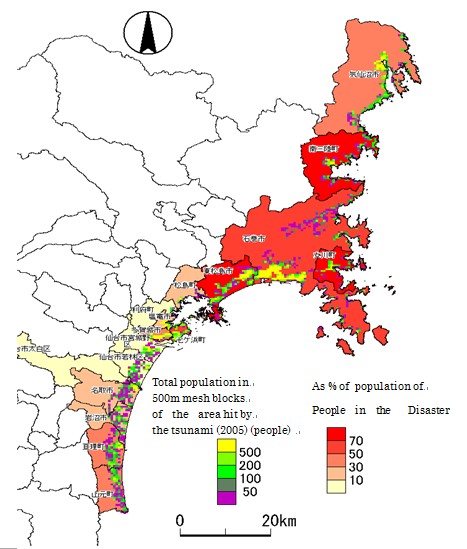

As you can see by looking at the graph and map of areas hit by the tsunami, the mortality rate for all residents in coastal areas is high, but the harder the municipality was hit, the higher the mortality rate for persons with disabilities is. In other words, the natural disaster tsunami is extremely deadly for people with disabilities.

- Mortality rate for residents and persons with disabilities in Miyagi (figures are only given for municipalities that have confirmed the death of persons with disabilities.)

| Number of residents, fatalities, and mortality rate |

Number of persons with a certificate for persons with disabilities, number of persons with disabilities who died because of the disaster, and mortality rate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents (Oct. 2010) |

Fatalities (Aug. 2012) |

Mortality rate |

Persons with a certificate for persons with disabilities (Mar. 2011) |

Fatalities (Feb. 2012) |

Mortality rate |

|

| Sendai-shi | 1,045,986 * 543,345 |

891 | 0.08% 0.16% |

40,233 * 22,791 |

53 | 0.13% 0.23% |

| Ishinomaki-shi | 160,826 | 3,471 | 2.15% | 7,683 | 397 | 5.16% |

| Shiogama-shi | 56,490 | 49 | 0.08% | 2,845 | 0 | 0.00% |

| Kesennuma-shi | 73,489 | 1,204 | 1.63% | 3,647 | 137 | 3.75% |

| Natori-shi | 73,134 | 944 | 1.29% | 3,453 | 76 | 2.20% |

| Tagajo-shi | 63,060 | 213 | 0.33% | 2,271 | 17 | 0.74% |

| Iwanuma-shi | 44,187 | 185 | 0.41% | 1,732 | 12 | 0.69% |

| Higashimatsushima-shi | 42,903 | 1,125 | 2.62% | 1,967 | 115 | 5.84% |

| Shibata-machi | 39,341 | 5 | 0.01% | 1,619 | 1 | 0.06% |

| Watari-cho | 34,845 | 264 | 0.75% | 1,537 | 23 | 1.49% |

| Yamamoto-cho | 16,704 | 697 | 4.17% | 912 | 54 | 5.92% |

| Matsushima-machi | 15,085 | 7 | 0.04% | 744 | 5 | 0.67% |

| Shichigahama-machi | 20,416 | 73 | 0.35% | 875 | 8 | 0.91% |

| Rifu-cho | 33,994 | 9 | 0.02% | 1,017 | 0 | 0.0% |

| Onagawa-cho | 10,051 | 595 | 5.91% | 520 | 81 | 15.57% |

| Minamisanriku-cho | 17,429 | 611 | 3.50% | 942 | 125 | 13.26% |

| Total Coastal area total |

1,747,940 * 1,245,299 |

10,343 | 0.59% 0.83% |

71,997 * 54,555 |

1,104 | 1.53% 2.02% |

The “*” for Sendai-shi is the total for Taihaku-ku, Wakabayashi-ku, and Miyagino-ku.

Number of residents and fatalities are figures released by Miyagi Prefecture; the number of persons with a certificate for persons with disabilities right before March 11, 2011, is based on JDF research.

- Mortality rate for residents and persons with disabilities in coastal municipalities

(Text)

(Text)

2. Impact of the disaster on persons with disabilities as viewed from activities of the JDF Miyagi Support Center

(1) Living conditions in emergency shelters for persons with disabilities and their families immediately after the earthquake (April - June)

The Miyagi Support Center, which opened on March 30, 2011, following a preliminary inspection of the disaster area on March 23, started to confirm the safety of persons with disabilities and launched support activities in the chaotic conditions immediately after the earthquake - there were shortages of gas and kerosene and insufficient supplies of products at supermarkets and convenience stores.

The Welfare Service for Persons with Disabilities Section, Health and Welfare Department, Miyagi Prefecture, created a document “Miyagi Shien Senta No Shokaibunsho” (Introduction to the Miyagi Support Center) for us, and with this in hand, we visited various locations, including emergency shelters and municipal government offices, and tried to ascertain the condition of persons with disabilities at the shelters. It was, however, extremely difficult to determine where persons with disabilities were since in the coastal municipalities that sustained devastating damage, both administrative organs and emergency shelters were in chaos.

As expected when the center initially launched operations, many persons with disabilities and their families were taking refuge in locations such as half-destroyed homes and support offices for persons with disabilities and schools for special needs since it was difficult for them to stay in general designated emergency shelters. Many of the designated emergency shelters were not barrier free, meaning that persons with physical disabilities had a hard time getting around. Furthermore, life in crowded emergency shelters, such as gymnasiums and community centers, is quite stressful even for persons without disabilities, and conditions were even more difficult for persons with severe autism or psychosocial disabilities; therefore, many people and their families could not even enter the emergency shelters. People who could stay in support offices for people with disabilities had it slightly easier, but there were cases when persons with disabilities and their families were forced to live out in their cars.

Furthermore, because locations where people chose themselves to take refuge, such as homes and support offices for people with disabilities, were not designated emergency shelters, they did not receive deliveries of food and daily goods. Therefore, many people had to survive on the food at the offices for several days. While there were some fukushi (welfare) emergency shelters (emergency shelters for vulnerable citizens), which were institutionalized through revisions to the Disaster Relief Act of 1996, not all disability support offices where people were taking refuge had received such a designation.

During our visits, we had 294 dialogues in April, 374 in May, and 437 in June (figures include multiple visits). During those dialogues, many of the comments we received were similar to those of people without disabilities, such as “I can't get around because there is no gas,” “I am all worn out as a result of the long stay in the shelter,” and “every aftershock brings back memories of 3.11,” but the following were opinions often given because of the disability the person had.

“I am concerned about how I will live since my certificate for persons with disabilities and other items were washed away,” “I am stuck in bed since my wheelchair and cane were washed away.” “the medication I received is not very effective, and it looks like I will run out of it before the doctor comes around again,” “my autistic son cannot take any more,” “there are no supplies of goods for disabilities,” and “my neighbors have started to clean up, but I cannot do anything because of my disabilities.” After the earthquake hit on March 11, people lived in uncertainty for a long one - three months in emergency shelters and half-destroyed houses with absolutely no privacy, which was unbearably difficult.

It was difficult, however, to ascertain overall conditions since people with disabilities who we were able to meet during visits to these shelters were only a small fraction of the people who have a certificate for persons with disabilities. The Miyagi Support Center repeatedly requested any form of cooperation that municipalities in coastal areas could provide in order to ascertain the conditions of the numerous people with disabilities and their families. In several municipalities, progress was made in ascertaining conditions for people living at home (not institutionalized or hospitalized) through surveys conducted during home visits in collaboration with parties such as public health nurses and helping to distribute taxi coupons, but the Act on the Protection of Personal Information was a hindrance, and one would have to say that it was difficult to get a full picture of the earthquake's impact on persons with disabilities.

Therefore, at that time, we at least visited emergency shelters, fukushi emergency shelters, and disability support offices, and using the information obtained from these visits, we worked on various fronts, including supplying items such as general daily goods and care goods, helping people get around, and supporting efforts to reopen offices.

At the end of April, the Northern Support Center in Tome-shi was established as the base for support activities focused on Kesennuma-shi and Minamisanriku-cho. The Miyagi Support Center in Sendai-shi handled other areas.

(2) Support for reopening disability support offices

At the same time as efforts were made to ascertain the impact of the disaster on persons with disabilities living at home, we worked to survey damage to facilities for disability support such as welfare facilities that support persons with disabilities and workplaces/group homes (referred to below as disability support offices). Details of the survey results are given later, but I would like to discuss the work we did to support the reopening of disability support offices.

During our visits to emergency shelters and fukushi emergency shelters, persons with disabilities and their families often expressed the wish that worksites would quickly reopen. However, as of May, few offices in the coastal areas, which sustained substantial damage from the tsunami, were in a condition to reopen. For offices operated by a social welfare council, the council was busy with managing and operating local emergency shelters and accepting and managing volunteers and had no time to reopen offices.

As for offices located in buildings that were completely destroyed, securing another building in the area hit by the tsunami was extremely difficult. Of course, many of the staff of government offices, social welfare councils, welfare corporation, and offices were also victims of the disaster. Although not knowing the safety of family members, staff were kept busy night and day not only providing support to residents and persons with disabilities impacted by the disaster and their families living in emergency shelters but also getting local government and offices running again. Even though the actual timing was different for each area, we began to examine reopening the various offices between the end of April and middle of May.

Both the Miyagi Support Center and Northern Support Center actively worked to aid the reopening of these offices. In particular, these centers tried to continually send staff to help reopen offices in various municipalities including Minamisanriku-cho, Ishinomaki-shi, Higashimatsushima-shi, Natori-shi, and Yamamoto-cho. Various other forms of support were also provided for reopening offices, including calling on disability support offices throughout Japan to help, securing and providing vehicles, repairing facilities and building temporary offices in collaboration with Association for Aid and Relief, Japan.

- Progress of visits/dialogues and support activities provided by the JDF support centers

| Month | Main support activities provided by the JDF Miyagi Support Center | Number of visits/ dialogues | JDF Support staff |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 |

|

294 | 1,316 |

| 4 |

|

||

| 5 |

|

374 | 1,363 |

| 6 |

|

437 | 1,245 |

| 7 |

|

161 | 684 |

| 8 |

|

292 | 726 |

| 9 |

|

429 | 909 |

| 10 |

|

140 | 208 |

| 11 |

| 78 | 406 |

| 12 |

|

(3) Condition of persons with disabilities and their families when they moved from emergency shelters to temporary housing (July - Dec.)

Around the end of May, people started applying for temporary housing, and drawings were held for housing units. Moving to temporary housing got into full swing around July, but in June, there was an increase in requests for aid related to getting to explanatory meetings and conducting preliminary looks of desired temporary housing. We had a 161 dialogues with people during home visits in July, 292 in August, 429 in September, 140 in October, and 78 from November through December 1, when the East Area Support Center was closed.

While there was an increase in requests related to inspecting and moving to temporary housing in July, there was also an increase in problems after people moved in. Many of requests from people moved in were related to gravel roads at temporary housing, difficulties related to getting around in wheelchairs and with canes due to steps, and the danger of easily slipping in prefab bathing rooms and toilets since they lacked grab bars.

Because the Miyagi Support Center focused on support for Ishinomaki-shi and Onagawa-cho, which were particularly hard hit by the disaster, the East Area Support Center was opened in Wakuya-cho in the middle of August, making it possible to provide support to the local community. In addition, support continued to be provided to Kesennuma-shi and Minamisanriku-cho through the Northern Support Center, and staff from mainly these two centers visited emergency shelters and collected requests related to moving to and living at temporary housing. (The Centers continued to provide support to municipalities such as Minamisanriku-cho and Ishinomaki-shi.)

In Minamisanriku-cho and Onagawa-cho, activities consisted of holding regulator discussions between public officials, public health nurses, Miyagi Support Center, and Northern Support Center, handling requests, exchanging information on support activities, and similar activities. As for Onagawa-cho, there was substantial cooperation between government officials, public health nurses, and the Municipal hospital OT/PT. In addition to exchanging opinions regarding Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) and Miyagi Prefecture information obtained from JDF and municipal information and organizing ways to make renovations to temporary housing, things that could be done through the various systems, and items that would be difficult to accomplish with the systems, efforts were made to help persons with disabilities and the elderly living in emergency shelters and fukushi emergency shelters move to temporary housing and to improve the living environment after moving in.

Welfare services for persons with disabilities, nursing insurance, reconstruction support system, and similar systems were used as much as possible, but when it was difficult to do so, support was provided using other methods including getting cooperation from Association for Aid and Relief, Japan and the private funding organizations.

Renovating temporary housing was particularly problematic. Although differences in opinion between the central and prefectural governments made renovations difficult, steps were eliminated with the cooperation of the Association for Aid and Relief, Japan, and the problem of grab bars and anti-slip goods for prefab bathrooms was resolved by using spring-loaded poles and anti-slip mats, both of which were recommended by Onagawa Municipal Hospital. While sharing information on requests to install these items with the city, the Miyagi Support Center did the installations, and the Onagawa Municipal Hospital was responsible for checking the safety and providing post-installation services.

There were various other additional requests for improvements to temporary housing, and while responding to each individual request, the offices provided support for moving from emergency shelters to temporary housing. During the first part of December, the last cases of support for persons with disabilities moving from emergency shelters to temporary housing were completed, ending the personnel support provided by the support centers. In Minamisanriku-cho, government officials, disability organizations, and the Northern Support Center continued to hold regular discussions after that, and these continued until March 2012.

(4) Damage to disability support offices

At the same time that the Miyagi Support Center opened, it launched a study of damage to disability support offices, mainly ones in coastal areas. The results of the first survey were released on April 20, 2011, and stated that 93 of the offices had been damaged, including 30 that had been washed away, burned down, or completely destroyed.

Using the results of this survey and data from a subsequent fact-finding survey conducted by Miyagi Prefecture, another survey was conducted on the state of reopenings of the 500 disability support offices in the prefecture starting in June. (As of June 15)

Of the 500 offices, many of the 235 offices that sustained no damage and 227 offices that were slightly damaged reopened sometime after the earthquake. Of the 38 offices that were washed away, burned down, or were fully or partially destroyed, 15 offices were reopened after the existing building was repaired, and 13 offices reopened in another structure, such as prefab building.

However, even as of June 15, three months after the earthquake, 10 offices were still closed and there was no idea when they would open. These included 5 group homes and care homes, 2 child day care offices, and 1 of each of the following: work continuation support b-type center, work/life support center, and local activity support center. As of August 31, 6 of these offices were still not open.

Even now, two years after the earthquake, there is still 1 office that is not open.

3. Future issues related to support for persons with disabilities affected by the disaster

I would like to now look at some issues that came to light on account of our activities.

(1) How information on people requiring help during a disaster is used

According to the Disaster Relief Act, municipalities are supposed to collect information on people who would have difficulty evacuating during a disaster, such as persons with disabilities and the elderly, and to use the information to help these people during a disaster. For the Great East Japan Earthquake, however, this did not occur smoothly.

The tsunami following the Great East Japan Earthquake caused devastating damage in an extremely large area, and immediately after the earthquake, many of the local governments in coastal areas were kept busy with various activities including operating emergency shelters, providing support to people at the shelters, undertaking operations related to confirming the death/safety of people, restoring basic utilities, and handling administrative procedures such as payment of donations etc., which made it extremely difficult for them to respond to individual people requiring help. Many of the social welfare councils in coastal cities were overwhelmed with operating shelters and handling volunteers, and for a long time, they could not start work on relaunching the offices they operated.

On the other hand, there were several cities whose city offices were completely destroyed by the tsunami and whose registry of and data on persons with disabilities were washed away. In these municipalities, the only way to check the safety of people and ascertain their living conditions at times was when they received a request for a new certificate for persons with disabilities and or taxi coupons were distributed. At that time, several municipalities provided support through home visits to persons with disabilities in cooperation with government officials, social welfare councils, public health nurses, and the Miyagi Support Center.

The lesson learned from this was that the registry of people requiring aid should be provided to private-sector volunteers and efforts should be made to ascertain the safety and living conditions of individual persons requiring aid. The Act on the Protection of Personal Information and ordinances make it possible to release public information when “it is necessary to protect the life, safety, and assets of a person and it is difficult to obtain the person's consent.” For example, in Kesennuma-shi, the municipal government provided parties such as residents' associations and local welfare commissioners (Minsei-iin community volunteers) with the residents registry and asked for the cooperation of residents in confirming the safety of others.

If there is an earthquake that causes major damage to local government administrative functions or it is necessary to ascertain not only the information of all residents but also the conditions and desires of people requiring aid, such as the elderly, persons with disabilities, and children, it is important to provide personal information to volunteer organizations that can work with the government and ascertain the safety of people and their living conditions.

(2) Improving the dispatch of support staff to disaster areas

Immediately after the earthquake, MHLW called on the staff at offices/facilities for the elderly, persons with disabilities, and children throughout Japan to register for possible work in the disaster area, and many such staff did so. As of March 22, 2011, 7,019 people registered, and 1,811 of these were in fields related to disabilities.

Although this prompt response is praiseworthy, the dispatch of staff did not progress as expected. This was because the offices/facilities receiving the staff was responsible for the cost of their transportation, lodgings, and wages.

After that, the MHLW released a revised administrative circular on April 15, which stated that transportation costs and lodging expenses were covered by disaster aid, but wages were still the responsibility of the local offices/facilities in damaged area receiving the staff. This was because offices/facilities were permitted to accept more than the set number of users, and the compensation regarding these users was the source of funds for the wages.

Many of these offices/facilities, however, accepted not only persons with disabilities eligible for at home support but also their families, but these people were not covered by the system. Furthermore, wages were set based on discussions between the dispatched staff and the receiving offices/facilities, and even though the offices/facilities wanted experienced staff, they could not pay high wages. On the other hand, groups dispatching workers had to send young or inexperienced staff since the wages were low; therefore, as of the April 15 administrative circular, the number of dispatched staff was substantially less than the number of staff that could be sent.

As of September 2, 2011, 7,719 staff members could be sent, around 1,900 of which were in the field of disability, but a total of only 148 people (19 to Iwate, 74 to Miyagi, and 55 to Fukushima) were actually sent (according to Dai 97 ho (97th Report) by the MHLW).

(3) Significance of the fukushi emergency shelters and improvements

Fukushi emergency shelters are extremely important for supporting vulnerable people in the case of an earthquake who have been forced to evacuate. For these people who find it difficult to live in general designated evacuation shelters, these are necessary support measures to meet their special needs. However, the Great East Japan Earthquake brought to light several problems.

First, for evacuees and people requiring aid, there was the problem that they had no idea where to find the fukushi emergency shelter.

Second, many of the disability support offices that volunteered to serve as emergency shelters did not know that they could be designated as a fukushi emergency shelter if they applied to the municipality.

Third, there was insufficient financial support for fukushi emergency shelters. Personnel expenses for one support staff for every ten evacuees is provided from disaster aid, but one support staff for every ten people is woefully inadequate to support people with disabilities, the elderly, and their families twenty-four hours a day. This needs to be promptly remedied at the national level.

Fourth, the longer people live in these shelters, the more difficult it becomes for the fukushi emergency shelter to return to their original use. In this sense, it is necessary to prepare measures to secure tertiary emergency shelters, which would include renting out community centers, other public resources, and private hotels.

(4) Current conditions of life as a natural disaster refugee at a facility such as temporary housing and issues that came to light

When building temporary housing, numerous issues came to light. In Miyagi, about 22,000 temporary housing units were built in the prefecture. Of these, there were 290 fukushi (welfare) temporary housing (temporary housing for vulnerable citizens) units that could be used for the elderly and as group homes for persons with disabilities. At first, Miyagi Prefecture planned to build 30,000 temporary housing units, but there were many people who wanted general rented residences, and in response to these people, a system of privately-rented accommodations used as temporary housing was created in which a rent subsidy (60,000 yen for a household of four) was paid (this was referred to as “deemed temporary housing”). Therefore, the prefecture reduced its plans for building temporary housing because 26,000 households desired privately-rented accommodations used as temporary housing. The construction of fukushi temporary housing was a new feature this time, and the following are problems related to temporary housing in general.

First, although it was clear that about 60% of the people impacted by the earthquake were elderly, sixty or older, there were numerous problems with temporary housing, such as many having numerous steps, and even if a ramp was installed, it was too steep. Particularly, prefab bathing rooms and toilets with no grab bars installed in the temporary housing made the housing difficult for many elderly and persons with physical disabilities to use. Even if efforts were made to attach grab bars later, there were many cases when that was impossible because of structural problems with the prefab bathing units.

Second, there was the problem that if people moved in to temporary housing that was located in municipality that they were not registered in, it was not possible to renovate the temporary housing using systems such as nursing insurance or one created by the Services and Supports for Persons with Disabilities Act. The municipalities included Natori-shi, Onagawa-cho, Kesennuma-shi, and Minamisanriku-cho, which sustained major damage, and a total of 1,117 units were installed, making it difficult to renovate the housing. At that time, it should have been possible to make the renovations using disaster aid from the central government, but Miyagi Prefecture was extremely reluctant to do so.

Furthermore, additional works such as installing wall insulation had to be done afterwards because measures to deal with the cold winters had not been prepared. Bath water could not be reheated in any of the prefab bathing rooms in temporary housing, which was a major problem for bathing during the cold winters.

Third, municipalities have not ascertained the situation for people living in privately-rented accommodations used as temporary housing, for which a rent subsidy is provided. This is because the central and prefectural governments are responsible for building the temporary housing, and the prefecture serves as the counter for applying for and paying rent subsidies for this type of temporary housing; therefore, municipalities have no idea where refugees living in this type of temporary housing are. Furthermore, in many cases the privately-rented temporary housing is located in a municipality that is not the one of the person's registered residence, and persons with disabilities and their families, for whom living in prefab temporary housing would be difficult, are probably living in privately-rented accommodations used as temporary housing, but for the reasons given above, it was impossible to determine the actual number of such people. Furthermore, since there are many situations when the person is not living in the municipality of his/her registered residence, whether support for home welfare services, etc. was provided was a problem. (It is now possible to receive such services even in a city that is not the one of a person's registered residence).

As of January 2012, there were 26,631 applications for privately-rented accommodations used as temporary housing, but as of November 2012, the number of people living in such accommodations had fallen to 21,479. This was because people had repaired or rebuilt their own homes and moved back there, and the number of people living in privately-rented accommodations used as temporary housing is gradually falling, with the number changing about 300 each month (according to Miyagi Prefecture report). However, there are no precise figures for people with disabilities and their families who live in privately-rented accommodations used as temporary housing, including the number of people moving each month.

Fourth, there is the issue of people who have taken refuge outside the prefecture. As of December 31, 2012, all the people who had taken refuge within the prefecture had moved to temporary housing or privately-rented accommodations used as temporary housing, but as of January 2013, 8,700 people were still taking refuge outside the prefecture. The number of such people increased suddenly in July, when people started moving to temporary housing, and rose again starting in November. These people who have taken refuge outside the prefecture probably include many people with disabilities and their families, and not only Miyagi Prefecture but also the central government lack various information on these people, such as the living and employment conditions.

Conclusion

It will take time for the disaster area to rebuild, and this is not limited to problems faced by persons with disabilities. Fukushima confronts the nuclear power plant problem, a problem that cannot be resolved solely through cooperation of residents and the local government. In this sense, the central government must promote responsible, aggressive, and sustained reconstruction policies. I would like to end the report by bringing up some issues from a basic perspective of disabilities.

First, there is the issue of quickly and precisely ascertaining actual conditions. It is necessary to create support measures for various situations, including when people live in their own homes, in temporary housing, or privately-rented accommodations used as temporary housing and when refugees live/work outside the prefecture.

Second, there are many remaining difficulties and obstacles due to disabilities in addition to the difficulties of the damage from the natural disaster. There is also the issue of revising and moving forward with reconstruction plans based on this. The reconstruction plans for many municipalities that sustained damage are limited to making the municipality more compact or are centered on recovery efforts. The smaller the city is, the more prominent this trend is, and it is not necessarily the fault of the particular municipality. Considering that the Great East Japan Earthquake is a national crisis, it is absolutely necessary that the government take responsibility and provide active, sustained support.

Third, if one bases things on the intentions and desires of people in the disaster area, it is natural that they want to restore their communities, including their pre-disaster lives, work, and personal relations, and the goal should be to create a society that is easier for everyone to live in than the one before the earthquake. This will lead to a society that everyone, including persons with disabilities and the elderly, can comfortably live in. This will lead to an inclusive society.

(This report was written in January, 2013.)