LIFE ON AND SLIGHTLY TO THE RIGHT OF THE AUTISM SPECTRUM

January 27, 2005

Musashino Higashi Gakuen Tokyo, Japan

PRESENTED BY Stephen M. Shore

Tumbalaika@AOL.COM

www.AutismAsperger.net

Good morning. It is my pleasure and my honour to be here to speak at the Musashino Higashi Gakuen. Thank you for having me. We are all here as part of the autism spectrum community. The autism spectrum community includes parents, family members, teachers, doctors, other professionals, and people with autism themselves. Most of us are inducted into the autism community by what I call the autism dragon. When the autism dragon strikes, many children lose their ability to speak, have temper tantrums, withdraw from the environment, may get involved in self-stimulatory activities such as spinning, and often have self-abusive behaviour.

I was struck with this autism dragon at 18 months, and my parents had no idea what to do. Where autism comes from continues to be a great mystery. Some of the areas that researchers are looking into as possible causes include genetics, vaccinations, diet, perhaps a change in the environment, maybe a virus that is picked up by the mother and then transferred to the foetus. In summary, even with all this research, we still have no conclusive evidence as to the cause or causes of autism. Many researchers believe that there is a strong hereditary component, which means there may be a hereditary pre-disposition in some people, which is then triggered by one of the other factors that I’ve listed here.

Let’s take a quick look at some definitions of autism. The Autism Society of America defines autism as a complex developmental disability occurring early in life, and considers it as a bio-neurological condition affecting the functioning of the brain. The Diagnostic Statisticians’ Manual (DSM IV-TR) characterizes autism with challenges of social interaction, communication, repetitive motions, and restrictive interests. However, if there is no significant clinical delay in developing verbal communication skills, many professionals will consider a person with autistic tendencies to have Asperger Syndrome. Arnold Miller, a researcher in Boston, Massachusetts, defines autism as anything that interferes with the central nervous system getting the necessary information from the environment. Miller’s definition is interesting because there seems to be something that prevents people with autism from getting necessary information from the environment, to interact or develop in a typical manner.

| ASA(2003) | A complex developmental disability that typically appears during the first three years of life. Autism Spectrum Disorder results from a neurological condition that affects the functioning of the brain. |

| DSM IV-TR(2000) |

Social interaction Communication (but no significant clinical delay) Repetitive motions and restricted interests |

| Miller(2000) | Anything that interferes with the central nervous system getting the needed information from the environment. |

One area that needs more attention paid to are the challenges of sensory integration. The senses can be divided into inner and outer senses. The outer senses include sight, touch, taste, smell and hearing. There are several inner senses; two that we’ll look at are the vestibular sense that is in the inner ear and helps us with balance, and the second one is the proprioceptive sense, which is in the muscles and joints. The proprioceptive sense tells us where our body parts are in space, and how much force to use to accomplish tasks. Everybody that I know on the autism spectrum has to deal with what I call sensory violations – some of the senses are turned up too high and too much information comes in; some of the senses are down too low and not enough comes in – and the data that comes in from the senses tends to be distorted.

Let’s consider the sense of sight. A friend and I were in a library, and I suddenly noticed her eyes vibrating back and forth very quickly. She said to me shortly thereafter “can we leave?” She had enough verbal ability to suggest that we leave. My friend, like many people on the autism spectrum perceive fluorescent lighting the same way most typical people perceive a strobe light. Hardly conducive to good studying! What about a child ? say an 8-year-old child ? who’s in a classroom lit with fluorescent lights learning maths, and his eyes are also going back and forth very quickly. This child will most likely have a very difficult time listening to the maths teacher and doing a maths worksheet. In fact, this child may even get up and turn off the light. When we see behaviour like this we can refer to it as challenging behaviour ? challenging for the teacher to determine the cause and to accommodate for the cause of the child’s actions.

We have to consider that this behaviour might be a result of what I call a sensory violation. This means we have to consider the environment as an important component of working with a child on the autism spectrum. Many children with autism have difficulty with haircuts. For some children it may be the sound of the electric cutters, it may be the sound of the scissors, and it might be the light touch of the hair falling on the head. For me it was the pulling of the hair on the scalp. When my hair gets cut it gets cut one hair at a time, and I felt every one. I know that kissing my father, for a number of years, was very difficult because his breath smelt of coffee and his beard was much too scratchy. Another difficulty that many people with autism have is keeping sounds that should be in the background, and sounds that should be in the foreground, which means for me when my wife is finished using a wind-up alarm clock to time her practise sessions on the harp, it has to be closed and put it underneath a big chair cushion so I can’t hear it. At first, after placing the clock under the chair cushion, I would come home at the end of a long day to find her very angry and looking for the clock. Then I would tell her it’s under the chair cushion, and ask her “doesn’t everybody keep their clock underneath their chair cushion?”

Let’s look at some of the inner senses. Some children are hypo sensitive in the vestibular sense. These are the children that you will see spinning around in circles, and they would spend all day riding roller coasters if you gave them the opportunity. The hyper sensitive children have what is known as gravitational insecurity. These children will be afraid to walk backwards, for example. The proprioceptive sense is what leads children with autism to seek deep pressure by, for example, crawling under a mattress or a futon. I love to ride on airplanes because when the airplane takes off there is a lot of vestibular proprioceptive input. And when there is turbulence in the air and the plane is bouncing up and down, and the wings are going like this, it’s because the plane is autistic, and I’m just enjoying the bumpy ride. And I think about all the brave little children that live through each day having to face these sensory violations. From what I have seen at the Boston Higashi School, their emphasis on physical education and movement is very helpful for dealing with these sensory issues that children with autism have, and it’s wonderful to see.

Let’s examine another challenge that children with autism face, and that is self-stimulatory behaviour. The definition of self-stimulatory behaviour it is repetitive non-functional behaviour. Let’s take a closer look at this behaviour. Most people, when sitting in a chair in a situation such as a lecture, play with their hair, scratch, perhaps doodle with their pen, or perhaps shake their legs up and down. What is this very common behaviour that we see in people? Almost everybody does it. It seems repetitive; it seems non-functional. So what is really happening with people that are doing this? It seems to me that people are not made to sit in chairs for long periods of time, and what is actually happening is that you are engaged in these behaviours in order to keep yourself alert. These behaviours help you to concentrate; they help regulate the arousal level of the brain. In the case of someone who is too anxious these regular activities will often help calm a person down. Regulating the arousal level of the brain may very well be what autistic children are doing when they clap, when they do this with their fingers, or are engaged in other self-stimulatory behaviour. So perhaps you may want to look at this as self-regulatory behaviour. The difference between many people with autism and most adults is that most adults have learned socially acceptable self-stimulatory behaviour. So if the flapping of hands is too intrusive in the classroom, maybe we can give the student a therapy ball to squeeze, or in the case of the Boston Higashi School, students with autism hold a recorder in music class to keep their hands busy. And that also helps them regulate their arousal level in the brain. I think that is a brilliant idea in the Higashi School.

| SELF STIMULATORY BEHAVIOR | |

| Official Definition Repetitive nonfunctional behavior |

Better Definition Self–regulatory behavior |

| Most adults have learned socially acceptable stims | |

Let’s consider the autism spectrum. One way to look at autism is from severe to light, and the severest is what most of society thinks of as autism – a small, vulnerable child unaware of the environment, perhaps having tantrums, perhaps being self abusive. This is what Leo Kanner wrote about in 1943 when he first brought the word autism into popular usage. Ranging all the way from moderate to the lighter end of the spectrum, we may see people with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s Syndrome, with very well developed and significant skills, for example, in verbal communication. I have a friend with Asperger Syndrome, who has a verbal IQ of over 200, an overall IQ of 176, and a performance IQ of 110. What these numbers tell us – the difference in these numbers – is that there is a disability. And while she may be able to talk better and faster than all of us, she still has significant challenges with social interaction and sensory integration. The red circle in the middle of the autism spectrum diagram shows where I landed on the autism spectrum at 18 months. While I had lost my ability to speak, I still had some awareness of the environment, and had receptive communication. Taking the diagram of the autism spectrum and stretching out the right hand side to allow us to take a look at how I moved along the autism spectrum. The red arrow on the autism spectrum diagram signifies that people with autism move towards the lighter end of the autism spectrum. Our challenge is to move them as quickly as possible and as far to the right as possible.

Let’s take a look at some things that have happened in my life, with autism. I had a pretty typical birth – only two hours’ labour, started turning over at 8 days of age, and at 24 hours my wife says I looked like an egg. At one-and-a-half years the autism dragon hit, causing withdrawal from the environment, tantrums and all those autistic traits and behaviours that we are familiar with. It took my parents a full year to find a place for me to get diagnosed. One full year!

There were no conferences on autism spectrum disorders and very few schools for children with autism at that time – and we’re talking about the early 1960s. At that time, autism was thought of as a very rare psychiatric disorder – a type of childhood schizophrenia that was caused by poor parenting, and in particular, poor mothering. I was evaluated as having atypical development, strong autistic tendencies, and [being] psychotic. My parents were told they had never seen a child that was so sick, and that they should send me to an institution. My parents refuted and convinced the school to take me, after a year. It was in that year that my parents had to apply early intervention. My parents were left without any information, and basically did what parents who love their child felt they needed to do in order to help their child develop and grow. It was mostly my mother, because in the mid 1960s it was customary for the father to spend the day at work, and the mother would stay at home and do mother-type things. Because there were no programmes for children with autism, and no concept of early intervention, we can only put what my mother did in today’s words. In today’s words we can liken what did to a home-based early intervention programme emphasising music, movement, sensory integration, narration and imitation. My mother would start by trying to get me to imitate her. When that didn’t work she turned around and started imitating me. When she imitated me, I became aware of her in my environment. Once I became aware of her in my environment, she was able to pull me in the direction that I needed to go. An important educational implication is that no matter what level the student is at – whether they have autism or whether they are a doctoral student – you have to meet the student and develop a relationship with them before you can teach them. This hard work for my parents emphasised the important role that parents play in helping children with autism. And for this reason we must be grateful to our parents, and recognise the importance of parents in determining the child’s education and future. So for this reason, I wish to thank Mrs. Suda and Mrs. Abe, and all of the parents in this room, who are working very hard to help children with autism. Thank you.

In scientific terms, my mother got within what is termed by Arnold Miller as the zone of intention. Arnold Miller has found that unlike most people who have an unlimited zone of intention, which allows people even in the back of the audience to perceive me up-front, many people with autism have such small zone of intention they may only be aware of another person in their presence if they touch them. The zone of intention may explain why I didn’t hear my mother call me into the house for lunch, but only became aware of her existence when she came over to me and touched my shoulder, and I’d immediately grab her hand and run into the house for lunch.

At age four I was beginning to learn how to talk again. I had entered the special school that had initially rejected me. Upon re-evaluation, instead of being considered psychotic, I was now considered to be neurotic. I had discovered the wonderful world of watch motors. I would take apart a watch with a sharp kitchen knife, take out the motor, play with the gears and the hands, and put it all back together again. There were no pieces left over, and the watch still worked. This led me to question how could I have such fine motor control to take apart a watch, but for me – and for so many people with autism ? why is writing by hand so difficult? Then when I got older and became familiar with computers, I found that typing my thoughts into g a computer was so much faster than writing by hand. I think the answer lies in two areas; the first area has to do with structure. A watch motor and a computer keyboard are very structured – everything is in the same place – and that is what guides us in, for example, how to take apart and put together a mechanical object. And as for a computer keyboard, all the keys are in the same place all the time. If you hit the key hard or if you hit it soft, you still get the same result. Writing by hand is so difficult because. It is much less structured – it’s just you and a piece of paper, and the fine motor control combined with the challenges of proprioceptive input – which tells you how hard to hold an object and how far to push a pencil or the pen – are difficult areas for people with autism, and that’s what makes writing so difficult. Even at this early age it is important to start building self-awareness into a person with autism. When you see that a person is particularly good at something, let them know about it; make a big deal, because what you are doing is planting the seeds for what is know as self-determination. Or in other words, people with autism realising they can work towards their strengths in order to lead a filling and productive life.

At age six I entered public-school kindergarten, which was a social and academic disaster. In the United States, students who have a disability or who are different are teased and bullied. The teachers are often not given the needed training to understand and teach children with autism.. I would spend a lot of time reading my favourite books on astronomy and other sciences, while sometimes wondering if there was more to school than my sitting at my desk and reading these interesting books. Perhaps I should be doing maths with other students, or reading. I think this meant that teachers didn’t know how to teach me, but since I did not exhibit behavioural problems in class, they just left me alone to do what I wanted to do. The issue of disclosure may come up at this time. It may be that this is the first time a child realises they are different from other people, and they may come home asking questions, such as why do I have to go to a special school, why do I have to see a special doctor, why do I have to see a special therapist and other children don’t? At this time we need to start to think about talking to the child about their characteristics, their strengths, their challenges and how they can use their strengths in order to perhaps overcome these challenges and lead a filling and productive life. By looking at autism as just a collection of characteristics and traits we can work towards removing the stigma of the condition.

At age eight a teacher told me that I never learned how to do maths. The teacher never noticed the foot high stack of astronomy books on my desk. Somehow I learned enough maths to teach statistics at college level. These days, teachers know a lot more about the importance of using a child’s interests and strengths to provide a proper education. Everyone learns better and faster about things they are interested in. With people on the autism spectrum this just happens to be even more so. Anthony Attwood, a professional who wrote Asperger's Syndrome: A Guide for Parents and Professionals, defines a special interest as an interest of such great intensity that it interferes with daily functioning. Whenever possible, you will want to consider using these special interests – the power and attraction to these special interests – in teaching your students. Some of my special interests

include:

| airplanes | astronomy | bicycles | earthquakes |

| medicine | chemistry | mechanics | electricity |

| electronics | computers | hardware | tools |

| psychology | music | rocks | geology |

| geography | locks | cats | dinosaurs |

| watches | shiatsu | yoga | autism |

Sometimes they will come, they will last a few years and then go, sometimes there’s more than one of them running at once. There’ll be a quiz on these interests at the end.

At age ten I was very concerned about the letter“ge.” I leaned the English grammar rule that you drop the “ge.” before adding an “ging,” and I was so afraid that when you dropped the “ge.” that it would get hurt. Another example of my taking things literally includes when a friend of mine said he felt like a pizza, and I told him that he didnt look like one nor he didn’t smell like one either. People with autism think literally thoughts, which can make understanding of idioms very difficult.

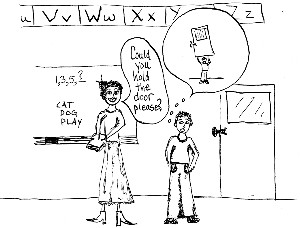

Another important challenge for people with autism is known as “The “Hidden Curriculum,” which is the title of a book written by Brenda Myles. The Hidden Curriculum refers to all of those rules that nobody talks about, but somehow everybody seems to understand.

Let’s take a look at this true example. A person with Asperger Syndrome is driving down a highway – Route 9 – with a speed limit of 55mph. A policemen using his radar sees that the young man is actually driving at 38mph. Because of the slow rate of speed, the policemen decides to follow him, and just like most drivers will do when they’re followed by a policemen, the young man with Asperger Syndrome pulls over to the side of the road. However, he pulls over to the left – into the grass meridian strip separating the two roads; causing the policeman to become very suspicious. Also because he has Asperger Syndrome the young man is not responding in the way that a policeman would expect. The policeman tests him for driving while drunk but finds that the person hasn’t drunk any alcohol at all. Fortunately, the person with Asperger Syndrome has the presence of mind to pull out a small card, which says on it “I have Asperger Syndrome. I am not dangerous. Please take me to a quiet place,“ and “Here’s the phone number of my father if you need more information.” Everything ended up well. This is an example of what can happen when someone with Asperger Syndrome; someone who is on the autism spectrum, and does not understand some of the unspoken rules. Tell a person on the autism spectrum to hold the door – which in the United States means to help open the door, and often they’ll get a picture in their mind of having to hold up the door.

At age thirteen I entered middle school. Although middle school tends to be very complicated for many children whether they are on the autism spectrum or not, it was actually easier for me because I realised two things: one was communicating with my classmates worked much better when I used words, and two, I finally figured out what teachers wanted from me in order to get properly evaluated for my work. I was also able to use my special interest and talent in music to be successful in band room, use that interest in building relationships with other people, and also for involvement in the community. For this reason I have chosen to teach children with autism how to play musical instruments, because it gives them a good leisure-time choice, and provides them with an easy way to develop relationships with other people and interact in the community by, for example, joining a community band.

At age nineteen I entered college and had more friends. If I wanted to ride a bicycle at midnight, I could find someone who was just as eager to ride a bicycle at midnight with me. College was a time when I discovered the idea of dating, which was very difficult for someone like me who has difficulty perceiving non-verbal communication and the subtle social interactions that go along with dating. However, during a graduate program in Music Education, I was fortunate enough to meet my wonderful wife, and we have been married for almost 15 years.

Another challenge we are facing, and we are in a unique situation because the study of autism has such a short history – only 60 years. I have learned that a new law regarding Special Education has just recently been passed in Japan. We have all of these children that we have been working with at the Musashino Higashi Gakuen and other schools for children with autism, and they eventually are going to graduate and become adults. In doing so, they will pass from a time when all of their education and needs are advocated for by parents, teachers and other professionals, and shift to a time when they are going to have to make their own needs for accommodations, wants and desires known is a way that others can understand and meet their requests.

What I have just described is self-advocacy. Teaching appropriate self-advocacy and disclosure remains a significant challenge to us as we prepare children on the autism spectrum ? who grow up into ? to know when and how to approach others in order to negotiate desired goals in order to build better mutual understanding, fulfilment, and productivity.

What I have just described is self-advocacy. Teaching appropriate self-advocacy and disclosure remains a significant challenge to us as we prepare children on the autism spectrum ? who grow up into ? to know when and how to approach others in order to negotiate desired goals in order to build better mutual understanding, fulfilment, and productivity.

With self-advocacy comes an amount of disclosure, which means having to tell someone about your autism, which that carries a degree of risk in that the other person may not be able to understand the situation. For example, suppose a person with autism is in a working environment that is lit with fluorescent lights, and they have sensitive eyes. They are going to have to tell their supervisor, in some way that that supervisor can understand, that they have a visual sensitivity to fluorescent light, and request to use a different type of lighting. That part of asking for the modification is the self-advocacy component to the request. The disclosure part is to state why the change of light is needed. That disclosure part may be very simple by just mentioning the sensitive eyes as the reason, and not mention the autism at all. With self-advocacy and disclosure you have to consider when to tell someone, how much to tell ? the whole thing or just the little piece that affects the area that you are in with this person, as well as who you are going to tell, and exactly what you want to accomplish. And you may realise that in a particular situation it just may not be worth disclosing one’s autism, but in other cases it may be. My second book, entitled “Ask and Tell:” is made up of contributions from six autistic people, entirely on the subject of teaching those with autism the skills of self-advocacy and disclosure, and it should be available in Japanese in about 6 months.

An important reason to consider for the necessity of self-advocacy and disclosure is that most people are busy with living; they are not thinking about how to accommodate people with differences. It’s not because they are rude or disrespectful, its just because people are busy with their own lives, which means that it’s up to people with disabilities to be able to communicate their needs through self-advocacy, and to make their disclosures in a way that others can understand.

| SELF-ADVOCACY DEFINED |

| Self-advocacy involves knowing when and how to approach others in order to negotiate desired goals, and in order to build better mutual understanding, fulfillment, and productivity. Successful self-advocacy often involves an amount of disclosure about oneself that carries some degree of risk, in order to reach a subsequent goal of better mutual understanding. |

Many people with autism go to college. There are a few things to consider in preparing persons with autism for college, and how to support them; enabling them to have success while there. The major key to keeping a person with a disability in college is support, and that support needs to come from the family, from friends, from the school, and perhaps from other professionals that are involved in this person’s life. By supporting a person with autism during their school days and during college, the amount of effort and resources put into providing that support now will be repaid many times over in with a person empowered to live as independently as possible, be employed, and be able to contribute to the community.

The college experience and I’ve broken it up into four main components, which need to be considered in developing a program for a person on the autism spectrum, or other disability, to be successful at a college level. For people with autism, when meeting with a disabilities’ office counsellor, I have found it useful to develop a worksheet involving writing down the challenges to being successful in school, the cause of the challenge, and the suggested accommodations. One college student I worked with was unable to take tests having multiple questions per page. In talking with her I found that the words on a full page of text were visually over stimulating. To her it seemed like the words all ran together preventing her from make any sense of the test. The student and I came up with two suggested accommodations: one of them was to rewrite the test so that there was only one question on a page, and the second one was to use two pieces of paper so that she could cover up the distracting verbiage. This person also has sensitivity towards fluorescent lights. As with the person I talked about earlier, she too perceives fluorescent lights as most others see as a strobe light; which can be very distracting. Some suggestions from the student included different lighting, perhaps sitting next to a window or wearing a baseball cap in class.

Another challenge for many people with autism includes scheduling long-term assignments as are commonly found at the college level. Our accommodation was to regularly meet with the professor to keep on target with all the sections of the long-term assignment. It is important to work with the student as much as possible on developing proper accommodations because they know best about their own needs. Involving the student in development accommodations empowers the student in making their own successful efforts in self-advocacy and disclosure as will be needed later on in life.

Let’s talk just a little bit as to what it’s like to have autism. What it’s like to experience the world as someone who has to think about things that most people take for granted. Let’s consider the task of speaking. There are two kinds of tasks: the first category is the multi-tasking type of task. More then on of these tasks can be done at one time. An example might be walking and talking to another person at the same time. We can say a lot of these tasks can be put in the background because they get done automatically – such as walking. Very few people think about how they walk – they just walk. Very few people think about talking. They just have an idea in the head and the words come out. The singular tasks are the second category and are processed in the foreground. These are tasks you have to give all of your concentration to, for example, learning how to drive a car for the first time.

I’ve listed here some typical multitasking tasks that most people do in the background. Most of you can listen to me talk and take notes at the same time. Most people can decode non-verbal cues automatically as a background task. Imagine if you had to tell a story to another person. That’s pretty easy; it’s no problem – that is until speaking is turned into a cognitive task. Now let’s take a look at cognitive tasks. Here I’ve listed a few cognitive tasks. One is driving for the first time; another might be doing mathematics in a second language. For many people with autism, listening to a lecture like this, and taking notes are both cognitive singular tasks, and are difficult to do at the same time. It’s the same for talking and making eye contact. And a third one is decoding non-verbal cues. I remember discovering non-verbal cues in college, and once I discovered the existence of non-verbal cues I spent hours in bookstores reading body-language books. Fascinated by the idea that body language was actually a previously unknown channel of communication, I was actually building a lexicon or dictionary of non-verbal communication that I can access as I am interacting with other people. However, unlike with most people not on the autism spectrum, persons with autism must consciously access and translate this nonverbal channel of communication. This requires additional effort.

| SPEAKING AS A CONGNITIVE TASK |

Associative – Multi-tasking – Background

|

| Adapted from: Lavoie, R. (1989). Understanding Learning Disabilities: How difficult can this be? (Videotape) Greenwich, CT: Peter Rosen Productions. |

Now imagine if you are to tell that same story I described earlier to another person, but you could not use any words that – if you are talking in English – contain the letter “n.” Or if you were talking in Japanese, imagine not being able to use any words that contain the sound “shi.” That would make it very difficult to talk. You could do it, but you would have to think so hard about talking that you really wouldn’t be able to do anything else, and it would be difficult for you to tell the story in an, easy, fluent manner. Talking in this manner is very similar to what it is like for people on the autism spectrum to engage in social interactions and other aspects of their environment.

I wish to thank everybody for being here. I want to thank the Musashino Higashi Gakuen as well as Boston Higashi School for inviting me here and making it possible for me to present for you. I want to thank all of the parents for all the effort and hard work you are putting into helping your children with autism. My appreciation goes to all of the teachers, other professionals, and everybody else who is in the autism community, for helping people with on the autism spectrum to lead fulfilling and productive lives.

Thank you.

This article was based on his lecture at Musashinohigashi-gakuen. He was invited by research project of NRCD Research Institute on "Assistive technologies to ensure safe and comfortable lifestyles of persons with disabilities" funded by "the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology" of Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

You can read Japanease version of this lecture at Musashinohigashi-gakuen HP.

URL:http://www.musashino-higashi.org/mrshorepresentation.htm