AHI’s Participatory Leadership Development Training – “Developing Human Resources for Inclusive Communities”

Kyoko Shimizu

Training Department Manager

Asian Health Institute

1.AHI and “health”

Asian Health Institute (AHI) is an NGO established in 1980 in Nisshin City, Aichi Prefecture. Over the following 40 years, it has been developing community leaders who encourage and support the people of Asia to take their health into their own hands.

In this context, “health” encompasses local communities in which the human rights of each person are protected, and where everyone is treated fairly and lives in mutual understanding and support: that is to say, an inclusive society. This is because we believe that these conditions are essential to physical and mental health.

The story begins in 1976, when a medical doctor, Dr Hiromi Kawahara (deceased), met a patient at a local hospital in Nepal where he was involved with medical cooperation work. She had travelled for several days from her village to the hospital to seek treatment for an injury to her leg sustained two years previously. Dr Kawahara realized that she had advanced skin cancer, and told her that her leg would have to be amputated in order to save her life. Her reply was as follows. “Please do not amputate it. I will die. Then my husband will be able to remarry a healthy woman.” So she returned to her village.

Why did she not come to the hospital right away? Why did she choose to die? The road to the hospital was bad, and it took several days on foot. During that time, she could not work and had to borrow money, which she had to continue working to repay. She had a lot of work, including taking care of her family and agricultural labour. If she lost her leg, there would be no support available from anywhere, and she would push her family even further into poverty…

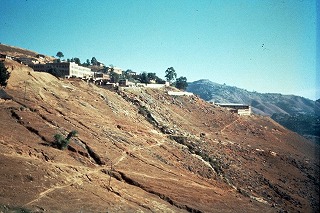

Photo: Tansen, the town in which the hospital where Dr Kawahara worked is located (in 1976, when he worked there)

Photo: Tansen, the town in which the hospital where Dr Kawahara worked is located (in 1976, when he worked there)

Dr Kawahara realized just how many lives could not be saved in hospitals. He also learned that in order to save lives and allow people to be healthy, it is necessary to tackle the various social issues surrounding them in their everyday lives which inhibit health.

2. Human resources development which spreads “from person to person”, and participatory training

Dr Kawahara also thought that tackling these issues must be done by the people directly impacted by them. When people who have been unable to exercise their innate power or raise their voices become aware of what is inside themselves and create more spaces to exercise this power, society will change. What is needed is not to make change happen from the outside, but the power to change from the inside. Given this, he decided to provide spaces where the people from those countries, those communities, could become aware of their abilities. These people would then create similar spaces in their own communities, so that even more people could become aware of and exercise their abilities.

The “human resources development” carried out by AHI is change spread “from person to person”. “Participatory” training is the key to generating a process by which people become aware of their abilities and develop them together.

AHI’s international training is carried out on the basis of these principles. Participants are workers for local NGOs supporting the activities of community members themselves, or leaders of community groups, and come from across Asia (around 10 – 15 participants each time; a total of 711 people have participated so far). The training lasts for six weeks. During this time, AHI provides food and accommodation (due to the COVID-19 pandemic, FY 2020 training was cancelled, and FY 2021 training will take place online). The main distinguishing characteristic is the participatory model, in which the participants take the lead in learning together.

First of all, the participants themselves decide on the training schedule and rules. The next topic for discussion is the study content. The work being done by each participant is extremely varied and diverse, ranging from topics directly connected to health, such as hygiene or  nutrition, to issues including raising incomes, the environment, education, gender, disability, and policy proposals. They each contribute their experiences and issues, find common goals, and decide what to study and how, using each other’s experiences as the teaching materials.

nutrition, to issues including raising incomes, the environment, education, gender, disability, and policy proposals. They each contribute their experiences and issues, find common goals, and decide what to study and how, using each other’s experiences as the teaching materials.

Photo: A scene from the training. The person standing in front is the participant facilitating the session. The participants sit in a circle so that they can see each other’s faces and how they are doing.

Once the content has been decided, the participants assign responsibilities and make teams, planning and facilitating each session. Not only the content but also the process (how to learn) is important. Some people do not speak English, the common language, well. Some are not self-confident. How can a space in which everyone learns together, without leaving them behind, be created? The participants help each other, think with each other, and move ahead through a process of repeated trial and error.

The teams also carry out daily tasks such as cooking breakfast and cleaning. These aspects sometimes cause surprise or conflict between the participants, who have different cultural, national, and religious backgrounds. They all gain repeated experience in talking together about how to overcome these, reconsidering their own values, and accepting differences.

The participants include workers with disabilities. Krishna from Nepal, a wheelchair user who participated in 2018, was one of these. The other participants had not previously had an opportunity to live together with a person with a disability, and so, for them, people with disabilities had always been the recipients of support. However, they were now the ones being  helped by Krishna, who spoke English fluently, and gave them advice on policy proposals. They realized that people with disabilities were also playing key roles in changing local communities, and were colleagues working together for the society at which they all aimed. After returning home, some participants began to make efforts to change their own activities so that people with and people without disabilities could work together.

helped by Krishna, who spoke English fluently, and gave them advice on policy proposals. They realized that people with disabilities were also playing key roles in changing local communities, and were colleagues working together for the society at which they all aimed. After returning home, some participants began to make efforts to change their own activities so that people with and people without disabilities could work together.

Photo: Krishna (second from left). In front is Hima from Nepal, who works to support Dalit women. After returning home, they made plans to promote collaboration between women and people with disabilities.

In other words, this training itself is a community in which different people come together. The participants play the central role in making it happen, learning and taking action in a diverse group. In doing so, they take on the challenge of creating an inclusive space in which all are respected and work together to solve problems. Through this process, they experience the changes in themselves and in the other participants, as well as the ability to grow together which these changes bring. They feel the potential of the participatory model to change communities, and after returning home, they put it into practice in their activities. This leads to the building of inclusive communities. At AHI, we also conduct follow-up projects to support these examples of practical implementation after the training, and further mutual learning growing out of the new challenges which the participants take on.

3. Activities carried out on the ground by workers with disabilities

Maman, an Indonesian whose use of his legs is impaired, took part in international training in 2004. At the time, he was the leader of a mutual self-help group for people with disabilities in an urban area. During the training, he felt the need to develop more leaders with disabilities through the creation of self-help groups, and after the training, he started to work for an NPO. He created mutual self-help groups in rural villages, where deep-rooted discrimination against people with disabilities persisted, and promoted entrepreneurial activities based on group savings. As they had more opportunities to go outside their homes, built relationships with their neighbours, and gained self-confidence, the members of the self-help groups spoke up about day-to-day issues and for their rights, working to create structures allowing them to  obtain road improvements or support with education and employment from the government and others.

obtain road improvements or support with education and employment from the government and others.

Photo: Maman (fifth from right) and the members of a self-help group for people with disabilities. They had got together that day to do the annual planning for the support activities for people with disabilities funded by village budgets (Klaten Regency, Java, January 2020)

In 2014, when he was the bureau chief, the NGO stopped its activities in rural villages due to funding difficulties. He quit his job and set up his own NGO to continue his activities on the ground. Many of the staff of the former NGO followed him, and are now working for the new NGO. Currently, fund raising is difficult, and the staff are working on a near-voluntary basis. What makes this possible is the existence of thriving leadership among people with disabilities in the local communities, and of their groups. They have already reached the point where they can take the activities in their communities forward themselves, without the full support of the NGO. There are groups which have set up regular forums for dialogue with the village or county administration, planning and proposing government policies for people with disabilities, and implementing these in partnership with other community groups. Maman himself is very busy as a welfare policy advisor to the national government.

We intend to continue inviting to our training workers from groups which tend to be left out, aiming to create momentum by which inclusive learning spaces and the learning which takes place there spread from person to person.