The 3rd Asia-Pacific CBR Congress

Title of submission: Leave No-One Behind: Top Ten Tips for Inclusive Development

Name of author: Siân Arulanantham

Affiliation/s of the author/s: The Leprosy Mission

E-mail address of the author: siana@tlmew.org.uk

Introduction

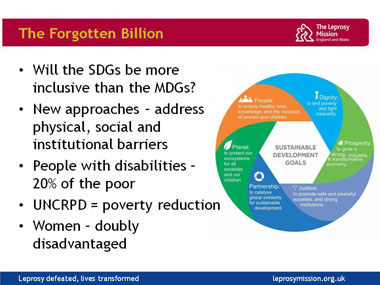

2015 brings the global challenge to develop Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that will not just halve poverty and reduce the issues associated with it, as the Millennium Development Goals attempted, but goals which will include all and ensure no-one is left behind (United Nations General Assembly, 2014). For this to be successful there will need to be a commitment to a different approach to development, not an approach that targets the ‘easy hanging fruit’ of those just below the poverty line, but one which addresses the physical, social and institutional barriers that presently excludes more than 20 per cent of the world’s poor from the development process (Arulanantham, 2014).

This paper will explore why disability inclusion is necessary; busting the myths of mainstream development practitioners who claim including disabled people is not relevant, too difficult or too expensive, and will draw on examples from the EC-funded Food Security for the Ultra Poor (FSUP) project in Giabandha, Bangladesh to highlight ten top tips for disability-inclusive development.

Why include disabled people?

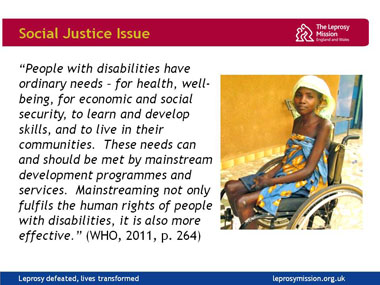

• Disability is a social justice issue. A disabled person is first and foremost a person, and entitled to the same rights as any other person. This is highlighted in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD, 2006).

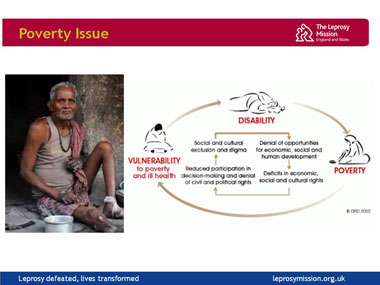

• Disability is a poverty issue. According to the WHO World Disability Report (WHO, 2011) disabled people generally have poorer health outcomes, have lower educational achievements, are less economically active and experience higher rates of poverty that their non-disabled counterparts. Thus, if a development project aims to target those most in need then it is clear that this group of people must be included.

• Disability is a gender issue. Disabled women are doubly discriminated and often victims of abuse. An example from the FSUP project: “Puppy is a 23 year old divorced lady. After a road accident she had a fracture in her right leg and so she got a bended leg and became physically disabled. For that reason her husband divorced her and sent her back to her parent’s house.”

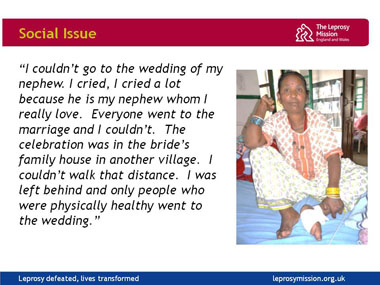

• Disability is a social issue. Disabled people often live in social isolation and are not invited to community events. Their families and community are often not aware of their capabilities and have low expectation. They can be seen as a burden on the family, ill-treated and confined to the home. Many disabled children do not attend school and those who do are often teased.

Barriers to Inclusive Development: Busting the Myths

Development programmes are often targeted at poverty reduction, gender discrimination, social injustice and health issues. These are all issues that affect disabled people and people affected by leprosy and other neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), so why are they not included? Government and mainstream NGOs use various excuses for lack of inclusion – let’s bust their myths!

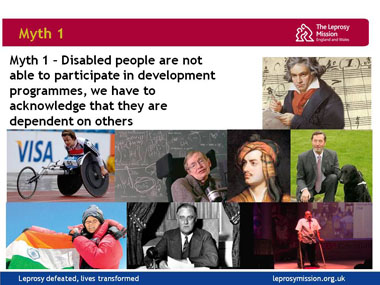

Myth 1 – Disabled people are not able to participate in development programmes, we have to acknowledge that they are dependent on others.

Just because a person has an impairment does not mean they cannot to contribute to their family and community. There are many examples of disabled people who have not only led fruitful, fulfilling lives but have made significant contributions to politics, sport and the arts, including Ludwig Van Beethoven - famous musician; Stephen Hawking - world famous physicist and mathematician; Arunima Sinha - first woman amputee to climb Everest; Franklin Roosevelt - polio survivor and 32nd President of the United States. They overcame the negative attitudes of Myth 1 that perpetuate exclusion; attitudes that keep disabled children out of school and hidden. Such attitudes must be dispelled for disabled people to reach their potential.

Unfortunately, for many disabled and leprosy affected people, discrimination has been so socially ingrained that they have come to believe the myth. This self-stigma often means they do not consider that opportunities, such as inclusion in development programmes, are open to them. They do not attend community meetings even if they know about them. Government and NGOs have to specifically look for disabled people and engage with them for inclusion to be successful.

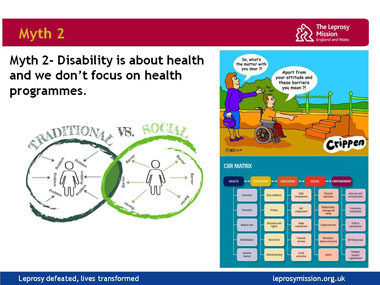

Myth 2 – Disability is about health and we don’t focus on health programmes.

It is common for disability to be associated with health and seen as a specialist medical area that NGOs do not have the skills to address. However, the social model of disability makes it clear that it is not the impairment that is disabling; it is the attitudinal, environmental and institutional barriers that prevent disabled people from actively participating in society. If barriers were broken down and the environment was universally accessible, then people with impairments would not be disabled. The WHO Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) Matrix (WHO, 2010), highlights that health is just one component of CBR. If development practitioners are involved in any CBR areas then disabled people must be included in their programmes for them to be inclusive.

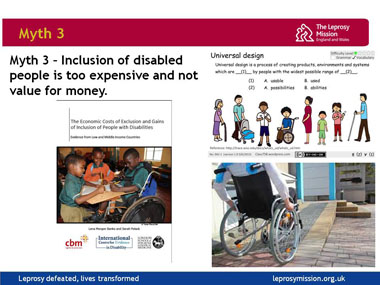

Myth 3 – Inclusion of disabled people is too expensive and not value for money.

Although it is true that there is a cost to inclusion which needs to be factored into programme budgets, this does not mean that inclusion represents poor value for money. Value for money is not just about reaching the most people for the lowest cost. It is about the quality of the intervention and the transformation that results. Bringing the extreme poor above the poverty line is likely to cost more than supporting those just below it. However, the impact may well be larger and the long-term savings higher, representing greater value for money. As DFID’s Disability Framework (DFID, 2014) highlight, planning inclusion from the start is the most cost effective.

Using the principles of Universal Design (Universal Design, 2015), buildings can be designed and constructed in a way which is accessible to all users, not just disabled people.

CBM and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine outline the Cost of Exclusion, highlighting that excluding disabled children from education “leads to lower employment and earning potential. Not only does this make individuals and their families more vulnerable to poverty, but it can also limit national economic growth.” (CBM & LSHTM, 2014). So Myth 3 remains a myth; in fact exclusion can be far more expensive in the long run, both economically and in terms of the quality of life of the individual.

Myth 4 – Inclusion of disabled people is too difficult and we can’t do it as we do not have the expertise.

It’s true that all organisations do not have expertise or experience of disability-inclusive development. However, for this very reason, mainstream organisations should explore how they can work in a consortium with others who have the relevant expertise. Partnering with Disabled People’s Organisations and specialist disability organisations will ensure that the needs of disabled people are better understood and the skills of staff developed, with the experts on hand as needed to give any technical input or advice required. This partnership working needs to start at the design phase of the project and include an objective of building the expertise of mainstream development partners in disability-inclusive development to ensure organisational sustainability.

Modelling Good Practice - Food Security for the Ultra Poor (FSUP), Bangladesh

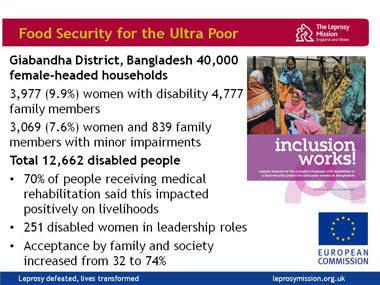

The EC-funded Food Security for the Ultra Poor (FSUP) project in Bangladesh was a good example of disability-inclusive development – see ‘Inclusion Works’ (Bruijin, 2014). A consortium of four mainstream Bangladeshi NGOs and two disability specific organisations were supported by four international NGOs to improve the food security of 40,000 female-headed households. The mainstream Bangladeshi NGOs were the main implementers with the disability specific NGOs providing support for physical rehabilitation, training and technical support to ensure inclusion of disabled and leprosy-affected people. Over 12,662 disabled people (disabled women-heads and family members) were included in the project who may well have been excluded from a mainstream development programme had inclusion not been made a priority. Physical rehabilitation services, such as counselling, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, provision of assistive devices (protective footwear, wheelchairs, crutches, glasses, canes and toilet seats), reconstructive surgeries and eye operations were provided by the disability-specific NGOs. This improved functional ability and psychological well-being of disabled people. 70 per cent of people receiving these services noticed positive changes in their ability to perform livelihood activities.

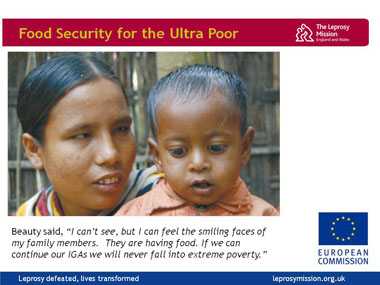

All 40,000 women in the project were supported with two different income generation activities (IGAs). Disabled women did the same activities as their non-disabled peers, although they were given priority for shop keeping and tailoring over more manual labour and supported with occupational therapy to ensure their IGAs would not worsen their condition. As a result of the intervention, many women stopped low paid labour work and begging. At the end of the project 100 per cent of households with a disabled person were still working on their IGAs. On average disabled women earned the same income from IGAs as non-disabled women.

However, since the project was based on the self-help group model, before IGAs could take place significant sensitisation work was needed with mainstream NGO staff and the general community for them to accept disabled women and women affected by leprosy into the groups. They needed to be convinced of their abilities; only after such activities was inclusion possible.

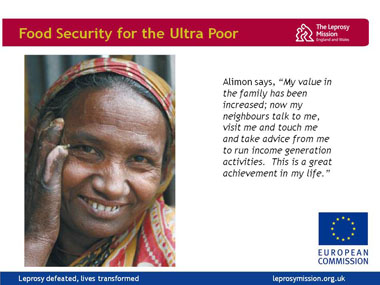

Disabled women said working was empowering and meant they were more respected within the family, as they were able to contribute to the family income. Being part of the women’s group improved their social wellbeing and helped them to escape isolation. Many disabled women took on leadership roles within their group and 251 disabled women were elected as members of the federation committees. Acceptance by family and society increased from 32 – 74 per cent.

So despite this project being implemented by mainstream NGOs, the technical input provided through partnering with disability specialists such as The Leprosy Mission, Light for the World and Centre for Disability in Development enabled successful disability-inclusive development.

So, what next? Top ten tips….

If the sustainable Development Goals are really going to leave no-one behind, then NGOs and Government programmes will need to include disabled people. Here are ten top tips for inclusion:

1. Before any call for proposals, develop links with organisations with specialisms in disability and build relationship so they can be partners in your programme.Having the expertise of a specialist as a partner (disability focused NGOs and/or Disabled People’s Organisations) means you are more likely to implement good practice and plan appropriately for inclusion.

2. Inclusion starts at the programme planning and proposal writing phase. Plan for inclusion, right from the beginning and make sure disabled people are involved in the process. Without planning for equal participation, it is unlikely that disabled people will automatically be included. This requires having accurate data on disability. If you don’t have specific data then make a thoughtful estimate and build some flexibility into your budget.

3. Make sure your needs assessment and criteria for selecting clients do not exclude disabled people. When you are doing your needs assessment, make sure disabled people are included. If they are not at your community meetings seek them out and talk to them. Make disability an explicit part of the project selection criteria, with a percentage target for inclusion.

4. Ensure all data is disaggregated by disability and gender in your M&E framework so that you have evidence of inclusion, otherwise it will be impossible to measure equal participation.Consider the different types of disability and ensure you are not just including those with physical impairment but are also people with sensory or intellectual impairment. Disabled women and girls often experience double discrimination. Ensure your M&E systems can demonstrate how many disabled women, men, girls and boys you are reaching.

5. Ensure all programme staff and the senior management teams of all implementing partners are trained in disability inclusion right at the beginning of the programme. Most barriers to inclusion are attitudinal. A change in staff mind-set is often needed so they recognise the potential of disabled people and eliminate stigma associated with diseases such as leprosy. Training senior managers to understand the importance of inclusion and how to achieve it is more likely to result in disability inclusion becoming part of organisational practice.

6. Accessibility needs to be taken into account in all aspects of the programme. This includes making sure meetings places are accessible, as well as ensuring that any construction is based on the principles of universal design. It is much more cost effective to plan accessibility into the design rather than to have to undo inaccessibility later.

7. Training should be planned in an inclusive manner, accessibility must be considered and the IGA chosen by the person should not lead to a further deterioration in their condition. This is particularly important for people with sensory loss due to leprosy or diabetes. Loss of sensation means certain types of manual work can lead to further disability. Occupational therapy aids could be used to prevent this, or an alternative livelihood may be more beneficial.

8. Ensure the disabled person remains at the centre of the intervention and maintains ownership. Family members can support where necessary but the disabled person needs to be enabled to actively participate in the intervention. Productivity and self-esteem is maintained and their potential reached only if the disabled person is the client, not the household.

9. Build access to disability rehabilitation services, e.g. physiotherapy, medical care, assistive devices, into your programme and budget for this. Often this rehabilitation support is needed in order for people to be able to undertake livelihood activities and for improved quality of life. Refer clients to other service providers or hire specialist who can provide these services.

10. Medical and rehabilitation services are only one aspect of inclusion. Social inclusion and the removal of barriers within a programme and community are equally important. In communities deeply ingrained beliefs and stigma often means that disabled people, particularly those disabled by leprosy, are not welcome. Sensitising community groups, particularly self-help groups members and community leaders, is important for the social acceptance of those affected by leprosy or disability, and ultimately for social integration.

Conclusion

More than one billion of the world’s population is disabled. One in five of the world’s poor (WHO, 2011). For them to be included in development and for the premise of the Sustainable Development Goals – Leaving No-one Behind - to be achieved there is a desperate need for society to include disabled people, including those disabled by stigmatising diseases such as leprosy. Mainstream NGOs and government programmes must be inclusive and involve Disabled People’s Organisations and specialist disability organisations in planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluation. Disabled women, men, girls and boys have a right to inclusion, to be allowed to fulfil their potential. They have ability! Disability inclusion it is not just about health, it is not too expensive and it’s not too difficult.

Bibliography

Arulanantham, S. (2014). Addressing inequality and exclusion - the opinion of people affected by leprosy in Africa and Asia, as to what should be included in any post Millennium Development Goal Framework. Leprosy Review, 133-140.

Bruijin, P. (2014). Inclusion Works. Retrieved 1 21, 2015, from Light for the World: http://www.lightfortheworld.nl/docs/default-source/capacity-building/inclusion-works.pdf?sfvrsn=4

CBM & LSHTM. (2014, July 16). Summary Report Cost of Exclusion. London: International Centre for Evidence in Disability.

DFID. (2014, December). DFID Disability Framework. Retrieved 1 15, 2015, from DFID: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/382338/Disability-Framework-2014.pdfDFID. (2014, December). DFID Disability Framework. Retrieved 1 15, 2015, from DFID: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/382338/Disability-Framework-2014.pdf

Stimpson, L. (1991). Courage Above All: Sexual Assaults Against Women with Disabilities . Toronto: DisAbled Women's Network-Toronto.

UN Enable. (2014, July). Enable Map. Retrieved 1 15, 2015, from Enable: http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/maps/enablemap.jpg

UNCRPD. (2006, December 13). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved January 2015, 1, from UN Enable: http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=150

UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre. (2007). Promoting the Rights of Children with Disabilities. Retrieved 1 15, 2015, from UN: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unyin/documents/children_disability_rights.pdfUNCRPD. (2006, December 13). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved January 2015, 1, from UN Enable: http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=150

United Nations General Assembly. (2014, December 4). United Nations Synthesis Report. Retrieved 1 15, 2015, from United Nations: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/69/700&Lang=E

Universal Design. (2015). Universal Design. Retrieved 1 21, 2015, from UniversalDesign.com: http://www.universaldesign.com/about-universal-design.html

WHO. (2010). Community Based Rehabiliation Guidelines. Retrieved 1 15, 2015, from WHO Disabilities: http://www.who.int/disabilities/cbr/cbr_matrix_11.10.pdf

WHO. (2011). World Disability Report. WHO.

WHO. (2014, April 4). Draft Disability Action Plan 2014-2021. Retrieved 1 15, 2015, from WHO: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_16-en.pdf

World Bank. (2008). Project appraisal document on a proposed credit to the People’s Republic of Bangladesh for a disability and children at risk project. Washington: World Bank.

スライド1 (スライド1の内容)

(スライド1の内容)

スライド2 (スライド2の内容)

(スライド2の内容)

スライド3 (スライド3の内容)

(スライド3の内容)

スライド4 (スライド4の内容)

(スライド4の内容)

スライド5 (スライド5の内容)

(スライド5の内容)

スライド6 (スライド6の内容)

(スライド6の内容)

スライド7 (スライド7の内容)

(スライド7の内容)

スライド8 (スライド8の内容)

(スライド8の内容)

スライド9 (スライド9の内容)

(スライド9の内容)

スライド10 (スライド10内容)

(スライド10内容)

スライド11 (スライド11の内容)

(スライド11の内容)

スライド12 (スライド12の内容)

(スライド12の内容)

スライド13 (スライド13の内容)

(スライド13の内容)

スライド14 (スライド14の内容)

(スライド14の内容)

スライド15 (スライド15の内容)

(スライド15の内容)

スライド16 (スライド16の内容)

(スライド16の内容)

スライド17 (スライド17の内容)

(スライド17の内容)