Paper presented at Japanese Society for Rehabilitation of Persons with Disabilities(JSRPD) Conference 2012

Traditional value systems and community based approaches to disability and livelihood.

Peter Coleridge

‘Development is what happens when relationships strengthen for the common good.’5

Introduction

I am very privileged to be invited to speak at your conference here in Tokyo. I have come from the other side of the world, and to bring someone so far immediately raises large expectations. I feel humbled and deeply honoured by this invitation.

My experience in working in disability has been entirely in developing countries, in particular, the Middle East, Afghanistan, India and Southern Africa. I do not have any experience of working in disability in an industrialised country where there is a well developed welfare system. But what I have to say is, I think, relevant to both industrialised and non-industrialised countries.

My experience goes back more than 30 years, and in that time there have been major changes, in attitude, in policies and in practice. Over the past decade or so I have focused on disability and livelihoods, and was the lead author for the chapter on livelihoods in the WHO CBR Guidelines, published in 2010. So I have chosen to speak about livelihood within the context of inclusive development.

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

When I survey the landscape in disability over the past 30 years, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (CRPD) stands out as a fundamental paradigm shift in attitudes and approaches to disability. Persons with disabilities are not viewed as objects of charity, medical treatment and social protection, but rather as subjects with rights, who are capable of claiming those rights and making decisions for their lives. The CRPD views disabled people as agents of their own change, and it envisions an inclusive society.

There are two things I would like to say about the convention. The first is that, while it is a major achievement, it will not change the lives of disabled people just by its existence. People cannot live on rights and legislation; they do not develop by an act of parliament.

6 An implementation strategy and process is required. The Convention is a set of standards that need to be implemented through policy and practice.

The second thing is that the idea of an inclusive society is not new. A main point of this talk is to draw attention to the traditional value systems in many countries, including Japan, where a fair, inclusive, humane society has been an essential part of traditional value systems. In this talk I am going to draw connections between traditional value systems and the CRPD, Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) and Community Based Inclusive Development (CBID). In industrialized societies we have largely lost sight of these traditional value systems, and these three tools, CRPD, CBR and CBID, can reawaken in us the age-old, profound ideals that are essential to our humanity.

The main driving force behind the CRPD has been the mobilisation of disabled people themselves. Their determination and persistence as a rights movement has had an enormous influence on public attitudes across the world. Where attitudes have changed most significantly is in the rehabilitation process, especially in non-industrialised countries, where CBR has become the dominant strategy for working with disabled people.

CBR and CBID

As attitudes have changed, CBR has itself gone through its own evolution. Whereas at the beginning in the early eighties it was primarily focused on rehabilitation, it is now viewed within a much wider framework: it is a multi-sectoral strategy to address the broader needs of disabled people, ensuring their participation and inclusion in society and enhancing their quality of life. CBR is now primarily about rights, poverty alleviation, and making inclusion a practical reality.

This radical change from rehabilitation to inclusion has given birth to the concept of Community Based Inclusive Development (CBID). Community Based Inclusive Development is a way of describing positive, mutually supporting relationships. Taking a close look at livelihood is a good way of illustrating what I mean by positive, mutually supporting relationships, which have been at the heart of age-old traditional value systems.

What does Livelihood mean?

Exclusion from economic activity is probably the prime reason for discrimination against disabled people in poor countries. Disabled people have lower employment rates and therefore are generally poorer than non-disabled people.

Work and employment are a crucial part of a person’s identity and self-image. We all have a built-in desire to contribute, to make a difference. It is also the way in which we are valued by our families and society.

Livelihood does not only mean employment or income. It is the way in which we organise our lives not just to survive but also to flourish – as human beings with desires and aspirations.

Can we measure poverty only in economic terms? Poverty is not simply lack of income; it is a denial of the fundamental freedom and opportunity to develop as a human being. The elimination of poverty lies in the creation of a just society in which all citizens have equal opportunity to develop their full potential.

There is a wide variety of ways CBR is implanted across the world depending on historical, cultural, political, economic, geographical, and many other factors7, but the common thread is that CBR is a practical strategy for creating equal opportunities. In some countries it also shows strong linkages with traditional value systems.

Consider the example of Opha in Zimbabwe.

Opha is a wheelchair user who sells fruit in the market in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Her husband left her because of her disability, and she has no children of her own. But she supports a niece to go through school.

She buys her fruit from a wholesaler, transporting one crate at a time on her lap in the wheelchair. Her earnings are about $50 a month.

She belongs to a range of community groups, including the local disabled people’s organisation, a church group, a savings group, and a residents’ association.

The first thing that strikes you about Opha is her happiness. She is smiling, positive, and outgoing. There is no complaint. She lives her life with a sunny, optimistic spirit.

The second thing that strikes you is that the price of her bananas is twice as high as her neighbour’s in the market. How can this be?

The answer is ubuntu. Ubuntu is a concept used in South Africa, and the same concept is also used in other countries of southern Africa under different names.

Desmond Tutu, a well-known South African leader, describes ubuntu as follows:

- “A person with ubuntu is open and available to others, affirming of others, does not feel threatened that others are able and good; they are based on a proper self-assurance that comes from knowing that he or she belongs in a greater whole; they feel diminished when others are humiliated or diminished.”

‘If others are diminished, I am diminished.’ We belong to a greater whole. We are not just individuals. We are part of a common humanity. There is connectivity between all of us.

What makes us human? I am a human because I belong. I participate. I share. In essence, I am because you are. I take my own meaning as a person from my relationships with those around me, and indeed from my relationships with the rest of mankind.

But increasingly as industrialization has progressed we have lost sight of this ideal and we think of ourselves as individuals.

Opha sells her bananas at a higher price than her neighbour because the principle of ubuntu still operates in Zimbabwe. She has a network of people who support her, and they are happy to pay more for her bananas simply because they are part of her support network.

Ubuntu also operates among the market traders. If Opha leaves her stall to go and collect fruit from the wholesaler, her neighbour looks after it. The market traders all help each other. This gives a totally different view of ‘market forces’ than the one presented by modern economists, who see the market as primarily competitive.

Opha says: “I fear God. I do not use money recklessly. I have an eye for detail. I make friends with my customers. If I am regarded as successful it is because of these things.”

But the real key to her success is that she does not sit at home ‘demanding her rights’. She is proactive, and approaches life with a positive and optimistic frame of mind. She reaches out to people, she makes friends, she gives, of herself, of her time, of her very limited money. She is part of a wide set of mutually supportive relationships.

Opha earns $50 a month. But is she poor?

The principles of the CRPD and CBR.

Let us remind ourselves of the principles of the CRPD.

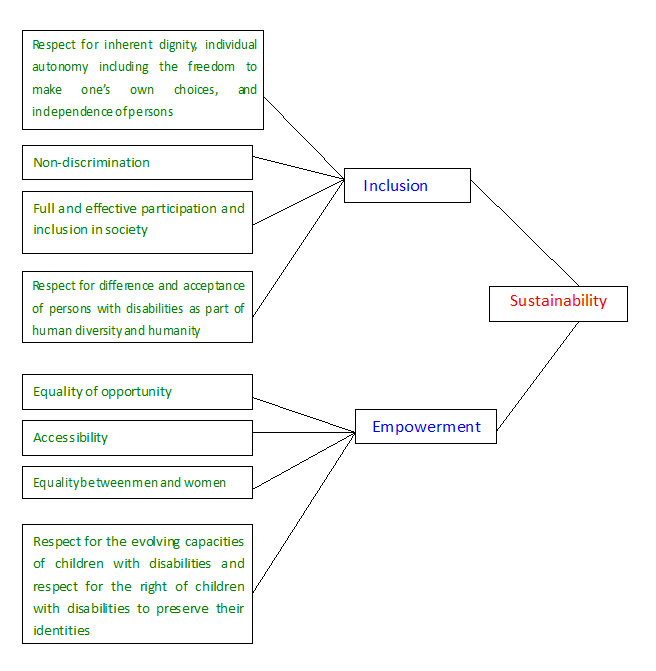

- Respect for inherent dignity, individual autonomy including the freedom to make one’s own choices, and independence of persons.

- Non-discrimination.

- Full and effective participation and inclusion in society.

- Respect for difference and acceptance of persons with disabilities as part of human diversity and humanity.

- Equality of opportunity.

- Accessibility.

- Equality between men and women.

- Respect for the evolving capacities of children with disabilities and respect for the right of children with disabilities to preserve their identities.

Eight principles are perhaps hard to remember. But they can be summarised in two words: inclusion and empowerment. And CBR, while adopting all the CRPD principles, adds sustainability.

These principles can also be summarised in one word: ubuntu. CBR is, at its best, a network of supporting relationships which provide purpose and value to the lives of all those concerned, not just of disabled people. The best CBR programmes:

- Involve multi-disciplinary teams, and/or staff trained in all aspects of disability and rehabilitation.

- Have staff who are aware of their own limitations and know when to refer to specialists.

- Develop programmes that are based on needs as expressed by the client groups.

- Train their staff in community development as well as technical skills.

- Recognise that CBR cannot exist in isolation; CBR is complementary to mainstream services and to more specialist services offered by various rehabilitation professionals.8

Here in Japan you have the concept of sampo yoshi, the theme of this conference. It will be explained further by others later, but in essence it means that tradesmen and craftsmen know that if they make a good product, people will want to buy it. If people buy it, the tradesmen make money, the customers are happy, and the community benefits. It is based on high quality workmanship and transparent dealing with customers. It is win-win-win all round.

Let me illustrate sampo yoshi by an example from India.

Leprosy Mission VTCs in India.

The Leprosy Mission runs a number of vocational training centres in India for young people who have leprosy, or whose parents have leprosy. Nowadays leprosy can be completely cured with drugs but the stigma remains very strong.

These VTCs train young people in motor mechanics, carpentry, electrical fitting, tailoring and the other vocational skills that VTCs teach all over the world. Many VTCs around the world have a rather poor record of employment for their graduates. But 90% of the graduates from the VTCs run by the Leprosy Mission in India find employment within a year of graduating.

Why? There are three reasons.

First, these VTCs focus not just on the technical skills but on life skills.

It is not enough to learn motor mechanics. To be successful in employment one also needs to have:

- Determination

- Aspirations

- Social responsibility

- Willingness to take risks

- Optimism

- Friendliness

- Persistence in the face of set-backs

- Creativity

- Openness to other views

- Critical thinking

- High personal standards

And these qualities can be taught, by example, by role models, and by creating a culture in the training centre where these values are demonstrated and prized.

Second, these VTCs have placement officers, whose job it is to develop relationships with potential employers and place graduates. Once a company has seen that graduates from these VTCs have so many valuable personal qualities besides their technical skills, they do not need persuading to take more.

Third, the schools have vibrant alumni associations, where previous graduates, now in jobs, can support younger graduates in finding and keeping employment.

These three factors, life skill training, placement officers, and alumni associations, are the secret of the success of these training schools. It is win-win-win all round. The graduates are happy because they get jobs, the employers are happy because they have people who can be relied on to do a good job both from a technical and a human perspective.

These schools operate on the basis of sampo yoshi because they know that training is more than just technical skills, that operating a successful car repair shop requires more than knowledge of motor mechanics: relations with customers and relationships within the workforce are equally important. A reputation for honest and transparent dealing in business will establish a secure and sustainable customer base. This reputation overrides all other considerations, including the fact that a car repair business employs people with leprosy, with all the stigma that that carries.

These schools also operate on the principle of ubuntu: through their placement officers and the alumni associations they build networks of mutually supporting relationships.

The CRPD and the new CBR Guidelines mark a paradigm shift in our view of disability because they see disabled people as agents of their own change, within a context of mutually supporting relationships. It is not that disabled people are now expected to do everything on their own and by themselves. The point is enshrined in the idea of ubuntu: if another human being is diminished, I am diminished. We are all part of a common humanity, in which it is entirely in our own interests to help each other.

The point has been understood by people at the grass roots level for centuries. But how do we establish this idea in government policy and make it common practice?

Governments are essentially reactive: they react to pressure from citizens (at least in democratic countries). So it is the responsibility of citizens to apply that pressure. The creation of a just society is a joint responsibility between government and citizens. Pressure from citizens takes many forms. In Britain we have just had the Olympics and Paralympics. The impact of the Paralympics on views of disability in Britain (and elsewhere) is incalculable. The stadiums were packed. Four million people tuned in to watch the final of the 100 metres. Media coverage was as wide as for the main Olympics. What happened in the arenas was headline news on the main news bulletins. For many people in Britain the Paralympics was more exciting and interesting than the main Olympics. We suddenly had a vision of disabled people achieving phenomenal levels of fitness and athletic prowess. As a wheelchair tennis player said, ‘There is nothing a disabled person cannot do.’

But we have to remember that before the first Paralympic competition in Britain in 1948, spinally injured people were regarded as having a life span of only a few years and were to be made as comfortable as possible for their remaining days. What an enormous distance we have come in the last sixty years! We have moved from a view of disability based on a very limited concept of rehabilitation to one where disabled people are seen as full participants and proactive agents of change.

The Paralympics are one example of very dramatic people-power in an industrialised country, but throughout countries in the Global South there are many examples where disabled people at the grass roots have been able to exert major influence on social development policy and practice.

One example: David Luyombo in Uganda is a man who demonstrates more than anyone else I have ever met the principles of ubuntu, sampo yoshi and the CRPD and the CBR Guidelines.

The story of David Luyombo

David runs an agricultural training centre in Masaka, about three hours drive west of Kampala. It runs short courses in animal husbandry and crop production using innovative and sustainable techniques. How it all happened is a remarkable story.

David had polio as a small child. He got himself educated primarily because his mother insisted he did so; she carried him to school when he was small, but when he grew she insisted he got there by himself. He can walk with difficulty using a stout stave as a crutch. (His father rejected him because of his disability.)

After leaving secondary school he trained as an accountant in Kampala because it was a job that was sedentary. But he did not want to be an accountant. He wanted to work for the development of disabled people in his home rural area in Masaka.

He reasoned that in a rural area what disabled people need is agricultural skills, like everyone else. Teaching them handicrafts does not make them self-sufficient. So he trained as a vetinary technician at Makere University, sponsored by a local NGO.

In 1990 he set out to mobilise disabled people on his own – by bicycle (despite the fact that polio made it hard for him to use a bicycle). He cycled all over the rural areas of his home district to identify families with disabled people. He focused on families, and not simply on individuals, for two reasons: first, in some cases the disabled person was a child and not ready to earn an income, or was too disabled to do so. Second, involving the whole family enabled them to see the disabled person as an asset, not as a liability.

He began to breed good quality cows, goats, pigs, turkeys and chickens, and to train disabled people and their families in better animal husbandry. He gave animals to these families on condition that they gave him the first offspring, which could then be given to another family.

David realised early on that to train people in better animal husbandry required a model farm and a training centre with accommodation, where people could come for training courses lasting several days. The farm has cows, cross-bred goats and pigs, and good quality turkeys and chickens kept in well-constructed pens. The result is that the training centre has now become a resource for rural development in the whole of Uganda, for both disabled and non-disabled people.

Lessons to be learned from David

- David identified the most obvious source of income for rural farming families: livestock, not crafts.

- He works with families, not with individuals.

- He acts as a role model for disabled people.

- He has a large vision, but started small.

- He works by demonstration.

- He has linked disability to other development issues.

- He has attracted the notice of people in mainstream development who have never linked their work with disabled people.

David’s sense of empowerment is reflected in his ambition to help others rather than just himself. He is making a success of his life because of a driving aspiration for development – of people, of disabled people, and of his area. This leads him to think creatively and positively, to plan, to continually seek ways to improve what he does. Initially people were sceptical about him; now they believe in him and he has become one of the driving forces for the development of a wide rural community.

David’s disability is now more or less irrelevant. Or rather it has been a trigger for transformation, in himself and in his community.

To conclude: CBR and CBID are strategies for creating networks of supportive relationships. ‘Development is what happens when relationships strengthen for the common good.’ Opha in Zimbabwe, the vocational training schools in India, and David in Uganda all remind is that traditional values like ubuntu and sampo yoshi are alive and well and are at the heart of CBR and CBID.

5 Malcom MacLachlan, Stuart Carr, Eilish McAuliffe (2010): The Aid Triangle. Recognizing the Human Dynamics of Dominance, justice and identity. Zed Books.

6 Cornielje, H & Bogopane-Zulu, H. The Implementation of Policies in Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) in Hartley et al. CBR Policy Development and Implementation UEA, (no date, but post 2006)

7 Ibid.

8 Adapted from Cornielje & Bogopone-Zulu.