GUEST EDITORIAL

PERSPECTIVES ON DISABILITY, POVERTY AND

DEVELOPMENT IN THE ASIAN REGION

Kozue Kay Nagata*

ABSTRACT

This study addresses the vital link between disability, poverty and development in developing Asian countries.

The social model of disability defines "disability" as the consequence of institutional and social discrimination, as well as exclusion of persons with impairments. It is possible that a comprehensive social model of disability can provide a new framework for explaining the complexity of disability, poverty and development, exposing disability as a cross-cutting developmental issue. Furthermore, adopting such a model will shift policy focus towards improving the social-economic conditions that currently restrict disabled people from full participation in life. However, it is still a valid fact that in developing countries, poverty is not only a dependent variable of social processes and social barriers, but also a root cause of many forms of impairment and disability. Thus, best practice is most likely to be ensured through an integrated approach, using best practice of both social and developmental terms.

This study aims at identifying priority areas for immediate action. Also, the empirical part of this study reviews and analyses the collective opinions and perceptions of those who took part in the questionnaire survey and focus group discussions, regarding disability rights, twin- track approach and priority areas, and targets for action by development agencies.

INTRODUCTION

Increasing the linkage between disability and poverty is gaining global recognition. The United Nations, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, USAID, DFID, JICA and other bilateral and multilateral aid agencies, have recently turned their attention towards disability mainstreaming and empowerment of persons with disabilities, adopting a so-called "twin track approach" --- an approach similar to the one advocated by the gender wing of some developmental agencies. This twin-track approach could be an effective tool to provide an enabling environment for disabled people to achieve greater livelihood security, equality, full participation in community life, and more independence and self-determination.

PERSPECTIVES ON DISABILITY: WHY DISABILITY IS

A DEVELOPMENT ISSUE

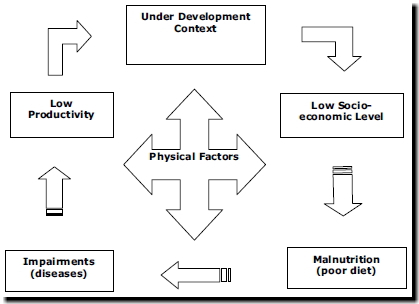

The mutual relationship between poverty and disability in the context of developing countries is shown in Figure 1. This demonstrates that the vicious cycle of underdevelopment starts as a result of economic poverty, leading to malnutrition and disease, which in turn will lead to impairment and disability, contributing to a low level of human development and low productivity in the community (1). As a result, there will be a need for huge investment in medical care and rehabilitation at the expense of prevention and early intervention, and often such investment does not materialise due to lack of funding. With this model, poverty alleviation and sustainable, equitable economic development may be considered a pre-requisite for prevention of impairment (2).

Figure 1: Disabled People and Economic Needs in the Developing World

Poverty is closely linked to impairment, and impairment to social exclusion. Another perspective about the relationship between poverty and disability mainly concerns the fact that disabled people are more likely to experience financial difficulties, as well as social and economic deprivation and discrimination, especially in developing countries of Asia. For instance, in Sri Lanka, 98% of deaf people who are employed earn less than US$ 2 a day, and 81 per cent earn less than US$ 1 a day (3). In this sense, poverty, like other consequences of institutional discrimination, restricts disabled people's rights and undermines their ability to fulfill their socio-economic obligations. The social model of disability is the foundation for this perspective. The social model achieved much progress in the disability movement through representation of disabled people's experience and proved a forceful pressure for enacting anti-discrimination laws and disability policy changes. It provided an aggressive challenge to the old paradigm associated with the medical model of disability.

The social model of disability defines "disability" as the consequence of institutional and social discrimination and exclusion of persons with impairments. Recently, disabled people in both developed and developing countries have increasingly challenged the traditional view that disability should be the same as impairment. The new International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (4) attempts to measure impairment and disability from a new perspective that is much closer to the social model, while striking a balance of the need for empowerment and improving the capacities of the individual and the need for eliminating the barriers and constraints of his/her social and physical environment (4).

DISABILITY, POVERTY AND DEVELOPMENT IN THE REGION

Acton (5) identified several factors in developing countries that may hinder attempts to empower disabled people, but also argued that the developed world must assume a part of the responsibility in confronting disability-related issues globally. There are several indigenous developmental obstacles hindering the efforts of achieving improved quality of life for persons with disabilities in developing countries, such as poverty, income disparity, cultural factors (e.g. kinship marriage), illiteracy and ignorance, misconception, armed conflict, faulty priorities, corruption, and so on. All of these are the elements of overall socio-economic and cultural development. For instance, in Jordan where a persistent social pressure in favor of consanguineous marriage still exists, a clear correlation between parental consanguinity and the incidence of severe mental retardation among children is frequently reported. The findings of the study conducted in Jordan by Staffan Janson (6), indicated a much higher kinship marriage rate of some 68% in the experimental group of parents of severely mentally retarded children, in contrast with the equivalent rate of 50% for the general population at the national level. Also, in Jordan, meningitis during infancy was found to be a major cause of childhood cerebral palsy in a sample survey conducted in the country (7).

While little is known in detail about the nature, scope and extent of disability in developing countries of Asia, not much more is known about how precisely disability and social discrimination are related to other forms of social exclusion. It is true that other forms of discrimination and social constraints, according to gender, social class, religion, ethnicity, caste, and so on, also affect the nature and problem of disability among people with the same level of impairments. Rural women with no income and no education are more severely disabled than wealthy, highly educated, urban men with the same physical and mental impairment. Therefore, in the discourse of disability and development, the concept of disability and the disability model must be re-defined, taking into consideration the complex fabric of a given society.

Poverty and disability share some similarity. Disability is often conceived as "a negative and static state" which requires intervention, rehabilitation and reduction. Interestingly, poverty used to be characterised in a very similar manner, as a negative endowment to be intervened and eradicated. Thus, by using the proposed comprehensive social model of disability, poverty per se can be understood more broadly as an outcome of social processes, including social exclusion, injustice and discrimination.

However, regarding the current modality of developmental interventions, some disability activists argue that development agencies still perceive disability in the developing world as primarily an individual problem and not part of the social and environmental context. In this sense, one can say that the persisting medical model approach which revolves around building capacity of individuals (disabled people) and individual coping skills for economic independence, has often ignored the importance of building up institutional capacity (social capacity) through removing social barriers, and changing the society itself.

A comprehensive social model can provide a new framework for explaining the complexity of disability, poverty and development, as it will reveal disability as a cross-cutting and interactive developmental issue. Furthermore, adopting such a model will shift the policy focus towards improving the social-economic conditions in which disabled people are currently positioned and restricted from full participation in life, and it will allow the creation of an inclusive, barrier-free, and rights-based society, a society for all.

Twin track approach

Over the last decades, and regardless of the large number of disabled people living in poverty in developing countries, disability has not been an important issue in developmental work, and rarely mentioned in any of the policy documents of international development agencies or international mainstream NGOs. Recently, however, there has been a growing interest in and concern about disability and rights of people with disabilities. The United Nations, the World Bank, USAID, JICA, and international NGOs have turned their attention towards disability and disability mainstreaming issues. Some of these agencies even began to formulate an official policy to mainstream disability into their work. This approach, which is similar to gender mainstreaming, means that the policies and projects should include disabled people's concerns as a key developmental issue. It also demands the active participation of disabled people in the design, monitoring and evaluation of developmental projects, including participatory planning and disability impact assessments. This approach of mainstreaming disability into generic development work is very similar to the proposed comprehensive social model of disability in principle, as both emphasise the cross-cutting and comprehensive nature of disability. The approach is also integrated and balanced, as it covers the need for empowerment of disabled people through networking, participation, CBR, capacity building, leadership training, etc.

The guiding principles of the twin-track approach to disability are reflected by a few policy papers of development agencies, such as "Disability, Poverty and Development" produced by the British Department of International Development (8) and more recently a paper by JICA on "Thematic Guidelines on Disability" (9). Some other development agencies, including a few UN agencies and the World Bank, are following this direction, and aiming at disability mainstreaming. They are increasingly seeing disability as a cross-cutting development issue. One important method of its implementation is to create a disability focal point, and/or introducing disability sensitising (equality) training for development agency staff, so that they can recognise the vital link between poverty reduction, other development priorities (e.g. education for all, and combating illiteracy) and "disability".

The 2005 World Summit outcome adopted in September 2005, recognised the need to guarantee the full enjoyment of the rights of disabled persons without discrimination (10). Therefore, incorporating the disability perspective into the international agenda is a mandate for all. In particular, action aimed at further implementing the Millennium Declaration and the MDG goals would result in effective fulfillment of the goals to realise improved standards of living, well-being, and human security on the basis of equality and inclusion of all.

This study incorporated the social model perspective, looking at poverty as an outcome of disability within the discourse of disability, poverty and development. However, the author argues that in most Asian developing countries, poverty is still among the most important causes of impairment, thus demanding a better balanced approach and broader perspective, such as a comprehensive social model approach to disability.

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

The study aimed to explore available information on policies and guidelines of development agencies on disability, poverty and development. The empirical part of this study reveals the collective views and perceptions about disability rights, twin- track approach, empowerment of disabled persons, and priorities for action, of three groups who participated in the survey and focus group discussions in Hong Kong-China, Japan, Thailand, Indonesia and several other countries of the Asian region.

- These groups are:

- (1) Official Development Assistance (ODA) workers,

- (2) Experts on disability issues,

- (3) Social workers/social work students

INSTRUMENT

Based on the findings of the preparatory focus groups in Thailand, a 27 item self-report questionnaire was constructed. Most questions were given as a bi-nominal choice of yes/no, while multiple choice questions of the 4-scale of (1) "not so important", (2) " important but not a priority", (3) "very important", (4) "top priority for immediate action" were used for substantive questions for priorities and action.

SAMPLE AND DATA COLLECTION

Data collection was based on convenience sampling, i.e., respondents (by group) were invited to complete the questionnaire on a voluntary basis. Overall, approximately 60 per cent of each group completed the questionnaire. Over a period of 7 months (June ? December 2005), a total of 195 questionnaire forms (15 ODA workers, 56 experts on disability, and 124 social workers/social work students) were collected. 15 of these collected questionnaires were considered invalid due to the lack of consistence and unreliability of the data. This left a total of 180 completed and valid questionnaires for analysis, of 15 ODA workers, 51 experts on disability, and 114 social workers/social work students. 10% of the respondents have some form of disability.

DATA ANALYSIS

The valid questionnaire data were verified and processed using the SPSS software package for windows as frequency, percentages, chi-square test, and ANOVA (to examine the differences among the occupational groups and analyse the patterns). The qualitative data from the focus group discussions, available documented information, and field visits to two good practice projects were also analysed for comparison and analytic induction.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the total of 180 respondents of three occupational categories, ODA workers (n=15, 8.3%), experts on disability (n=51, 28.3%) and social workers/social work students (n=114, 63.3%).

Of the total (180 respondents), 111 (61.7%) were female and 69 (38.3%) were male. A

much higher proportion of social workers/social work students (76.3%, n=87) were female

compared to ODA workers (53.3%, n=8) and experts on disability (31.4%, n=16) (x2 =30.589,

p<.01). The mean age of social workers/social work students (Mean=23.84, SD=8.006) was

significantly lower than that of ODA workers (Mean=40.93, SD=10.720) and experts on

disability (Mean=41.94, SD=11.564) (F=76.091, p<.01).

|

|

ODA Worker (n=15,8.30%) |

Expert on Disability (n=51,28.30%) |

Social worker* (n=114,63.30%) |

Chi Square | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics |

% | n | % | n | % | n | x2 | p |

| Gender Male Female |

46.70% 53.30% |

7 8 |

68.60% 31.40% |

35 16 |

23.70% 76.30% |

27 87 |

30.589 | .000 (a) |

| Age (years) Range Mean (SD) |

26-63 40.93 (10.720) |

24-71 41.94 (11.564) |

18-56 23.84 (8.006) |

F=76.091 .000 (b) | ||||

| Contact with disabled persons Yes No |

60.00% 40.00% |

9 6 |

98.00% 2.00% |

50 1 |

49.10% 50.90% |

56 58 |

36.653 | .000 (a) |

| Relationship with disabled person(s) as: Family member Yes No |

13.30% 86.70% |

2 13 |

31.40% 68.60% |

16 35 |

3.50% 96.50% |

4 110 |

25.519 | .000 (a) |

| Service target Yes No |

46.70% 53.30% |

7 8 |

54.90% 45.10% |

28 23 |

28.90% 71.10% |

33 81 |

10.648 | .005 (a) |

* Including social work students

(a) Chi-square test

(b) One-way ANOVA test (F=76.091)

Concerning previous contact with disabled persons, experts on disability reported a wider variety of exposure to and interaction with disabled people. Also, there was a significantly different pattern of interaction for each of the three groups. For instance, a much higher proportion of experts on disability had previous contact with disabled persons as family member (31.4%, n=16) than that of ODA workers (13.3%, n=2) and that of social workers/social workers students (3.5%, n=4) (x2 =21.519, p<.01). The overall exposure of social workers to disabled persons was rather limited; only to their contact with disabled persons as service target.

The knowledge about various human rights instruments of disability and basic national disability law was rather limited for social workers, but ODA workers and experts on disability had a better understanding of those instruments (Table 2). For instance, 82.4% of experts on disability knew about the ongoing process towards a new international convention on the rights and dignity of disabled persons, compared to that of 53.3% for ODA workers and 32.5% for social workers (x2 =35.294, p<.01).

| Respondents know the process towards an International Convention |

ODA Worker | Expert on Disability |

Social worker |

Chi Square | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | x2 | p | |

| Yes No |

53.30% 46.70% |

8 7 |

82.40% 17.60% |

42 9 |

32.50% 67.50% |

37 77 |

35.294 | .000 |

Table 3 shows that the majority of the total respondents (55.0%) supported the twintrack approach to disability and development, rather than focus merely on empowerment of disabled persons (16.1%) or mainstreaming into development work (28.9%). However, social workers or social work students, whose primary role is delivery of direct social services to disabled end-users, showed a tendency to support disability specific empowerment projects more than other categories. 21.1% of social workers/social work students chose "empowerment of disabled persons" as more important, compared to none for ODA workers and 9.80% for experts on disability (x2 =9.632, p<.05). Regarding the knowledge of ODA policy in their own countries, there was significant difference among ODA workers (91.70%), experts (38.50%) and social workers/social work students (8.0%) (x2 =54.559, p<.01).

|

|

Total | ODA Worker Disability |

Expert on worker |

Social | Chi Square | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | x2 | p | |

| More emphasis on disability mainstreaming into overall development projects |

28.90% | 52 | 40.00% | 6 | 39.20% | 20 | 22.80% | 26 | 9.63 | .047 |

| More emphasis on special projects on empowerment of disabled persons |

16.10% | 29 | 0.00% | 0 | 9.80% | 5 | 21.10% | 24 |

|

|

| Equal balance | 55.00% | 99 | 60.00% | 9 | 51.00% | 26 | 56.10% | 64 |

|

|

About questions concerning empowerment and mainstreaming, as indicated in Tables 4 and 5, overall there was a wide difference among the three occupational categories of respondents. On the empowerment side, training and capacity building of disabled persons and their representative organisations was rated as the top priority for immediate action, by 66.7% of ODA workers, and 66.7% of experts on disability, compared to only 28.9% of social workers/ social work students, who noted that this is considered a significant variation among the groups (x2 =33.887, p<.01).

| Importance of empowerment projects |

ODA Worker | Expert on Disability |

Social worker |

Chi Square | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % |

|

% |

|

% |

|

x2 | p | |

| Training and capacity building of persons with disablities and their organisations Not so important Important, but not a priority Very important Top priority for immediate action |

0.00% 0.00% 33.30% 66.70% |

0 0 5 10 |

3.90% 0.00% 29.40% 66.70% |

2 0 15 34 |

0.00% 11.40% 59.60% 28.90% |

0 13 68 33 |

33.887 | .000 |

| Advocacy related activities Not so important Important, but not a priority Very important Top priority for immediate action |

13.30% 53.30% 13.30% 20.00% |

2 8 2 3 |

3.90% 21.60% 37.30% 37.30% |

2 11 19 19 |

0.90% 28.10% 57.90% 13.20% |

1 32 66 15 |

29.084 | .000 |

Furthermore, on the mainstreaming side, there is a statistically significant difference among the

three occupational categories. For instance, concerning the introduction of universal design, 60.0% of ODA workers and 47.1% of experts on disability rated this as the top priority, compared to the equivalent of 27.2% for social workers/ social work students (x2 =19.132, p<.01). However, ODA workers were much more hesitant to support the establishment of a quota for disabled people in general training projects, as 33.3% of ODA workers regard this as "not so important", compared to 5.9% for experts, and 3.5% for social workers (x2 =29.331, p<.01). This may be related to ODA workers' worry and concern about an evidence-based accountability that may be imposed on them, for their follow-up action.

In mainstreaming of participation of disabled persons in decision making, only 28.1% of social workers considered this the top priority, compared to that of 93.3% for ODA workers and 62.7% for experts on disability (x2 =38.619, p<.01). One can say that ODA workers and experts were more supportive to participation of disabled persons in decision making than social workers/social work students.

On the contrary, ODA workers tend to show reservation towards pro-active and positive measures such as priority recruitment of disabled employees, and/or introduction of disability budgeting. 40% of ODA workers considered disability budgeting not so important, compared to none for experts and only 2.6% for social workers (x2 =46.863, p<.01). Also, priority recruitment of disabled employees was considered "not so important" by 33.3% of ODA workers, compared to that of 3.9% for experts, and 5.3% for social workers (x2 =46.863, p<.01). In contrast, ODA workers tend to support more gradual mainstreaming mechanisms such as disability sensitising training for development workers, and 80.0% of them considered sensitising training as the top priority for immediate action, compared to that of 49.0% for experts, and 14.9% for social workers/social work students (x2 =40.501, p<.01).

| Importance of disability mainstreaming activities |

ODA Worker | Expert on Disability |

Social worker |

Chi Square | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | x2 | p | |

| Introduction of "universal design and physical accessiblity" into infrastructure projects Not so important Important, but not a priority Very important Top priority for immediate action |

0.00% 0.00% 40.00% 60.00% |

0 0 6 9 |

3.90% 15.70% 33.30% 47.10% |

2 8 17 24 |

0.00% 28.90% 43.90% 27.20% |

0 33 50 31 |

19.132 | .004 |

| Promotion of "inclusive education" in education projects Not so important Important, but not a priority Very important Top priority for immediate action |

0.00% 13.30% 60.00% 26.70% |

0 2 9 4 |

0.00% 7.80% 39.20% 52.90% |

0 4 20 27 |

0.00% 17.50% 53.50% 28.90% |

0 20 61 33 |

10.146 | .038 |

| Establishing a quota for disabled beneficiaries in general training projects Not so important Important, but not a priority Very important Top priority for immediate action |

33.30% 33.30% 13.30% 20.00% |

5 5 2 3 |

5.90% 31.40% 37.30% 25.50% |

3 16 19 13 |

3.50% 24.60% 58.80% 13.20% |

4 28 67 15 |

29.331 | .000 |

Different measures were rated on a scale of 1-4, with 1 as the lowest (not so important) and 4 as the highest (very important). Measures such as supporting the training and capacity building of disabled persons (Mean=3.33), network of disabled persons (Mean=3.14), CBR (Mean=3.16), introducing universal design (Mean=3.11), inclusive education (Mean=3.21), promoting the participation of disabled persons in decision making (Mean=3.27), establishing a disability focal point (Mean=3.02), introducing disability sensitising programmes for ODA workers (Mean=3.07), and formulation of a set of accessibility guidelines for infrastructure projects (Mean=3.18), are rated relatively high by all the groups combined. Measures such as support to advocacy activities (Mean=2.87), establishing a quota for disabled beneficiaries (Mean=2.77), introducing disability impact assessments (Mean=2.96), disability budgeting and priority recruitment of disabled employees in development agencies (Mean=2.84) are rated relatively low by the all groups combined.

Discussion from focus groups

Overall, there was strong recognition of the importance of disability as a development issue, rather than a social welfare issue, and an issue closely linked to the priorities of bilateral and multilateral development agencies and generic international development NGOs.

However, the link between poverty and disability was better understood by ODA workers and experts on disabilities, than service providers (i.e., social workers and social work students). This may be due to their limited exposure to developing countries and development work, and the pedagogical emphasis on the needs-based service delivery of social work. Perhaps, due to the very basic nature of social work, and their strong commitment to it, social workers/ social work students may see "empowerment of disabled persons" (through vocational training, CBR, leadership training, etc.) as a very important target area. Social workers/social work students are also less supportive of advocacy related activities and networking of self-help groups of disabled people. This may be a reflection of their professional and patronising attitudes to a certain degree.

The twin-track approach to disability was appraised highly by all occupational groups, as a development and project initiative. Only a few experts on disability (including those with disabilities), expressed some caution towards this approach, as they think that this approach may make accountability less clear and more diffuse.

There is a need for the development of a set of good indicators for success and failure of mainstreaming initiatives. Imposing very strict reporting obligations by the local missions of development agencies, and introduction of more participatory and interactive techniques for evaluation of development projects (both generic projects and disability specific projects) were among the proposals made by all three groups.

There was a strong feeling about an urgent need to increase knowledge about disability and development, both in theory, and practice, and to identify good practice projects in the region, implemented by various development partners.

A few experts on disability proposed the adoption of more participatory appraisal such as participatory rural appraisal (PRA), in the production of a comprehensive study on disability and development, which includes an extensive review of literature and analysis of successful project initiatives in each country of the region.

The lack of funding in promoting the twin-track approach was raised by both ODA workers (Japan, Thailand) and experts on disability (Indonesia, Thailand). A few senior ODA workers confirmed that budgetary allocation would be required for mainstreaming disability as well, contradicting the myth of "mainstreaming of disability not requiring any extra budgetary allocation".

The majority of experts on disability (particularly those with disabilities) thought that a clear definition of disability and approach would be central to designing a disability policy or strategy. The proposed model, a "comprehensive social model" was highly rated by the majority of ODA workers and social workers/social worker students; however, some experts on disability advocate the more radical social model of disability, which sees disability purely as discrimination and inclusion. They are concerned that an emphasis on the developmental aspect of disability (including poverty and disability) may reverse the perspective and attention towards the old medical or individual model.

Some experts on disability proposed that development agencies make a more concerted effort for removing the institutional and social barriers in a recipient country, through enhancing their technical support in formulating appropriate policy such as dispatching an expert on disability legislation and policy.

The majority of ODA workers had reservations concerning introducing proactive and affirmative action to promote inclusion of disabled persons, such as priority hiring of disabled employees, introducing a disability budget or establishing a quota for disabled beneficiaries in generic training. They seem to prefer a less drastic approach, such as a disability sensitising programme for staff.

CONCLUSION

Development agencies should integrate disability concerns into the mainstream of their development work, policy and practice by adopting a well-balanced, comprehensive social model approach to disability, which is well reflected by WHO-ICF and the twin-track approach. To achieve this end, the twin-track strategy advocated by some international development agencies such as DFID and JICA (along lines similar to gender issues) should be utilised.

All stakeholders, including ODA workers, experts on disability, and professionals for service delivery (such as social workers) should recognise the importance of disability as a development issue, rather than a mere social welfare issue. The introduction of disability sensitising training and the mandatory obligation of reporting of disability impact of all generic projects may be an effective initial step towards this goal. More action-oriented research is required to identify and compile examples of best practice for the empowerment of persons with disabilities, mainstreaming and the twin-track approach in developing countries of the Asian region.

In designing, monitoring and evaluation of development projects (including generic projects), disabled persons and/or their representative organisations should be invited and involved in assessment and evaluation within their local or national contexts.

Also, a more participatory research modality, such as PRA, action-oriented research and participatory learning and action (PLA) should be introduced in the process of research production on disability, poverty and development.

More elaborate discussions and debates may be required to consider positive and proactive measures, such as setting up a quota scheme for disabled people in training courses, disability budgeting, and affirmative action on hiring disabled ODA staff.

Sufficient budgetary allocation should be made available to support delivery of the twin-track approach. It is important to recognise the budgetary need, to implement disability mainstreaming into development work.

Parallel to the process towards an international convention on promotion and protection of the rights and dignity of disabled persons, development agencies should promote the paradigm shift from a charity-based approach to a rights-based approach. In this context, knowledge by development workers and others, of the existing human rights instruments such as the Biwako Millennium Framework (BMF), the Standard Rules and the International Convention should be upgraded.

*Senior Economic Affairs Officer

Development Cooperation Policy Branch

Office of ECOSOC Support and Coordination Division

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

United Nations, HQ, New York, NY 10017, USA

e-mail: nagata@un.org

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a comprehensive study produced for the United Nations by the author, during her United Nations Sabbatical leave (September - December 2005). The data collection of the study was made possible through the assistance of Professor Ryosuke Matsui (Faculty of Social Policy and Administration, Hosei University Japan), and both Professor Joseph K. F. Kwok and Professor Raymond K. H. Chan (Dept. of Applied Social Studies, City University of Hong Kong-China). When this article was prepared, the author was a focal point for disability matters, at the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP). However, the views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or UN ESCAP.

REFERENCES

- Mezerville, G. Poverty and Development: Disability and Rehabilitation in Costa Rica. University Centre for International Rehabilitation, East Lansing, London, 1979.

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. Capabilities and Needs of Disabled Persons in the ESCWA Region, ESCWA, Amman, 1989.

- Ministry of Social Welfare. Sri Lanka, National Policy on Disability for Sri Lanka, Cabinet Paper 03/1292/155/013, Colombo, 2003.

- World Health Organisation. International Classification for Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO-ICF), Geneva, 2001.

- Acton, N. "World Disability: The Need for a New Approach", In: O. Shirley (ed.) Poverty and Disability in the Third World, Third World Group and AHRTAG, Fromme, 79-87, 1983.

- Janson, S. et. al. "Severe Mental Retardation in Jordanian Children", Bulletin of the Consulting Medical Laboratories, 1988;vol. 6 (2).

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. The Role of Family in Integrating Disabled Women into Society, ESCWA, Amman, 1994.

- Department for International Development. Disability, Poverty and Development, London, 2000.

- Japan International Cooperation Agency. JICA Thematic Guidelines on Disability, Tokyo, 2003.

- United Nations. General Assembly resolution 60/1 of 16 September 2005, New York, 2005.