From Special Education to Inclusive Education Moving from Seclusion to Inclusion

Sultana S. Zaman

General Secretary (Hon), Bangladesh Protibondhi Foundation

(Foundation for the Developmentally Disabled)

Shamim Ferdous

Chief Paediatrician, Bangladesh Protibondhi Foundation

(Foundation for the Developmentally Disabled)

Shirin Z. Munir

Executive Director, Bangladesh Protibondhi Foundation

(Foundation for the Developmentally Disabled)

Afroza Sultana

Special Education Teacher, Bangladesh Protibondhi Foundation

(Foundation for the Developmentally Disabled)

Jason McKey

Job Placement

Australia

Abstract Rights to education should be applied to both disabled and non-disabled children. To reach the goal of "education for All", an inclusive school system has been experimented in Bangladesh. The article below is to describe the efforts made by the Bangladesh Protibondhi Foundation and the effectiveness of the inclusive schools as a pilot scheme is also evaluated.

Introduction

Education as human rights has been recognized and affirmed in various national and international conferences including Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 26), Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 28), World Conference on Education for All (1990), the Salamanca Conference (1994) and World Education Forum (2000) where UNESCO, UNDP, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank, etc. and agencies and representatives from all over the world gathered to review and analyze their efforts towards the goal of "Education for All". Consequently, Inclusive education is regarded as the only means to achieve the goal of "Education for All".

The Salamanca Statement

More than 300 participants representing 92 governments and 25 international organizations met in Salamanca, Spain, from 7 to 10 June in 1994 to further the objectives of "Education for All" by considering the fundamental policy shift required to promote the approach of 'Inclusive Education', mainly to enable schools to serve all children, particularly those with special educational needs. The Conference adopted the Salamanca Statement on Principles, Policy and Practice in Special Needs Education and a Framework for Action.

The Salamanca Conference marked a new point for millions of children who had long been deprived of education. It provided a unique opportunity to place special education within the wider framework of the "Education for All" (EFA) movement. The goal is nothing less than the inclusion of the world's children in schools and the reform of the school system. This has led to the concept of "Inclusive School". The challenge confronting the concept of "Inclusive School" is that of developing a child-centred pedagogy capable of successfully educating all children, including those who have serious disadvantages and disabilities.

To provide quality basic education to all children is now a globally accepted reality (World Declaration on Education for All, 1990; Delhi Declaration, 1993). In developing countries, the focus is on access and participation with a reasonable level of achievement, while developed countries are concentrating on enhancing standards of achievement. A second trend is also discernible. School systems in developed countries have historically operated a parallel system of ordinary and special schools and now they are moving from "mainstreaming" and "integration" towards the development of "Inclusive Schools" (Ainscow, 1993). For school system in developing countries, inclusive schooling is not an alternative choice but an inevitability. The goal for both is to organize effective schools for all children, including those with special needs. Planning and implementing this qualitative change to the system is a challenging task (Jangira, 1995).

Although the goal of organizing effective schools for all is common to all countries, the magnitude and nature of the task would vary according to whether it is a developed or developing country.

The school system must be changed to enable it to respond to the educational needs of all children, including those with special needs. Each school has to accept that it must cater to all the children in its community. This fundamental shift in school policy is to be accompanied by: curriculum reform ensuring it accessibility to all children; teacher education reform to equip mainstream teachers with appropriate knowledge and skills; and the building of a support system (Jangira, 1995). From Special Education to Inclusive Education 17

Jayachandran (2000) who is a pioneer in introducing successful integrated education in the State of Kerala, India states that "Inclusive Education" is an integral part of general education. Training regular classroom teachers in the area of integrated education, curriculum modification, parent education, appropriate technology and modification, awareness of parents and modification of positive attitude towards disability are the key points of successful integrated education. We have formed a state level and district level Resource Group to develop the manpower required in special education and it has become the back bone of the scheme recently. Preparation in the early stage is the major factor that makes our special schools become the pilot Resource Centres for training of teachers, peers and volunteers.

Seva-in-Action, a voluntary organisation in India has made an attempt to understand the needs of people in rural areas and its relation to the community strengths in developing an appropriate Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) and Inclusive Education (IE) models. Seva-in-Action has developed a cost-effective, socio-culturally appropriate, comprehensive, sustainable and holistic Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) programme and Inclusive Schools aiming at total rehabilitation of all children and persons with disabilities in rural areas of Kamataka, South India (Nanjurdaiah, 2000).

Bangladesh Protibondhi Foundation (BPF) has been working for children with disabilities since 1984. Starting with early identification and screening, the foundation at present has become a full fledged service delivery organization reaching all over the country. But BPF's services for children with disabilities were based on the medical or expert model where disabling condition were diagnosed by experts and intervention prescribed by specialized people or experts and special schools were organized.

It has been realized that in a poor country like Bangladesh, the education and training needs of large number of children with disabilities cannot be met by costly special schools and centres, which create a segregated life situation. Also to comply with the trend of inclusive education which has gained a momentum with the movement to challenge exclusionary policies throughout the world, BPF is gradually shifting from the medical model to a more social model and has started CBR programmes in different parts of the country.

BPF has involved in more inclusive educational approach since 1999, when a twoweek workshop on "Inclusive Education" using the UNESCO "Teachers Education Resource Pack" was organized. This workshop focused on helping teachers in regular schools to respond positively to diversity and to explore new teaching approaches.

Further follow-ups have been difficult due to the lack of adequate professional support from the participating non-government organizations (NGOs) and the lack of interest at government level. However, for piloting of the "Inclusive Education" system, seven schools which were set up in BPF's CBR project areas at Dhamrai, Kishoregonj, Savar, Norshingdi, Nabinagar, Faridpur and Mirpur (Urban), have started inclusive schools in 1998 and 1999.

The following types of children are presently attending the BPF's inclusive schools:

- Children with learning difficulties or low intelligence (Down's syndrome, Turner's syndrome, Microcephaly, Hydrocephaly, Hypothyroidism with speech delay, improper speech, mild to moderate intelligence). All of them are educable or trainable.

- Children with Multiple disabilities (cerebral palsy having physical disability, or with learning problems, speech difficulties, hearing problems, vision problems, etc.)

- Post Polio Paresis.

- Osteogenesis Imperfecta (brittle bone disease).

- Epilepsy with mild learning difficulties.

- Autistic traits etc.

There is a large number of children from poor socio-economic background and they have no access to any educational programme within the area. The parents are unable to meet the basic needs of their children, such as food, clothing and medical care, etc. BPF is committed to include all these children into their schools so as to make sure that no one was left out of any education programme.

Having had a long experience of training and teaching children with different types of disabilities from different backgrounds, BPF is in a good position to address the needs of children with different learning needs. Children with motor, hearing and visual impairments were readily accommodated in the classrooms by providing special aids and resources and/or removing architectural barriers. To address the learning needs of children with intellectual disability, the curriculum content and teaching methods had to be made flexible and specially designed according to the individual child's needs and requirements. To remove socio-economic disparity, school uniforms were introduced. Nutritional supplements and medical treatments were provided to all the children of the schools.

The present study was launched to evaluate the overall situation of all the seven pilot schools of "Inclusive Education" situated in the six rural CBR centres and one urban centre?Dhamrai, Savar, Norshingdi, Kishoregonj, Nabinagar, Faridpur and Mirpur of Dhaka city.

Methodology

The evaluation was done by conducting 15 focal group discussions in which parents, teachers and non-disabled students in five out of seven centres were invited to participate.

Unstructured interview, informal discussion, observation and documentation are applied.

There were two moderators and one observer chosen from BPF to help conducting the FGD. The moderators were given a training on how to facilitate FGD including the explanation of the aims and purposes of the study. The moderators had never met the target participants before. Each discussion session lasted for more than 90 minutes. Informal discussion started through exchange of greetings. To establish rapport with the parents, teachers and students before the formal beginning of the FGD, different kinds of discussions on their families, children's problems etc. would be initiated.

In addition, overall academic performance of disabled and non-disabled children in all the seven "Inclusive Schools" were also evaluated.

Focal Group Discussion (FGD)

- Parents:

- Five randomly selected parent representatives from each of the five centres joined the focal group discussion (parents were either of the disabled children or the non-disabled children). Five FGD of parents were conducted in five centres.

- Teachers:

- Five teacher representatives from each of the five centres took part in the focal group discussion. Teachers were either from special schools or regular schools. Five FGD of teachers were conducted in five centres.

- Students:

- Five non-disabled students attending "Inclusive Schools" representing each of the five centres participated in the focal group discussion. Five FGD of students were conducted in five schools.

The following table lists out the numbers of parents, teachers and students included in the focal group discussions.

| Name of School | No. of Parents | No. of Teachers | No. of Non-disabled | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| of disabled children | of non-disabled children | Total | of inclusive schools | of refular schools | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| Mirpur Inclusive School | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Dhamrai | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Savar | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Norshingdi | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Kishoregonj | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Total | 14 | 11 | 25 | 11 | 14 | 25 | 12 | 13 | 25 |

Evaluation of Academic Performance

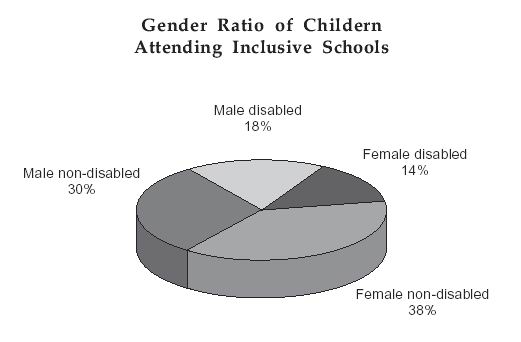

Evaluation of academic performance made by all the students enrolled (disabled and non-disabled) in the seven pilot "Inclusive Schools" at Dhamrai, Savar, Norshingdi, Kishoregonj, Faridpur, Nabinagar and Mirpur were measured. The following tables (Tables II & III) show the enrollment status of students in all the seven schools.

| Name of School | Disabled | Non-disabled | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | ||

| Mirpur(Urban) | 24 | 13 | 21 | 19 | 77 |

| Savar | 6 | 4 | 18 | 21 | 49 |

| Dhamrai | 8 | 4 | 22 | 54 | 88 |

| Norshingdi | 13 | 7 | 20 | 15 | 55 |

| Kishoregonj | 13 | 12 | 28 | 24 | 77 |

| Nabinagar | 11 | 11 | 12 | 23 | 57 |

| Faridpur | 10 | 12 | 19 | 16 | 57 |

| Total | 85 | 63 | 140 | 172 | 460 |

D

D| Enrollment to Different Grades of the Six Schools | No. of Students | Total No. of Students | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disabled | Non-disabled | ||

| Play Group | 16 | - | 16 |

| Nursery | 34 | 59 | 93 |

| Grade I | 66 | 147 | 213 |

| Grade II | 29 | 72 | 101 |

| Grade III | 1 | 17 | 18 |

| Grade IV | 2 | 13 | 15 |

| Grade V | - | 4 | 4 |

| Grand Total | 148 | 312 | 460 |

Academic performance of the students of inclusive schools were evaluated through: simple class tests and mid term tests in all the subjects taught from play group to class V. These tests were conducted through oral evaluation, work sheet, and written test on numbers, words, simple arithmetic, questions on stories, etc. following the curriculum of the text book board for each class. Evaluation on the part of the children with disabilities were also made flexible with special adaptation for each individual child.

Results

Focal Group Discussion with Parents

- Parents of Disabled Children:

- Most of the parents of disabled students opined that negative attitude of the society of excluding their children from mainstream education formed the biggest barrier to "Inclusive Education". Parents were very enthusiastic regarding "Inclusive Education" through which they were able to send their children to the mainstream schools. The parents of rural areas were also satisfied with all the activities of the schools particularly the food supplement provided for all the children. The parents also revealed that they had learned new ways of helping their children, and they were able to think about their children's abilities more realistically. Most of the parents, however had a fear of losing the service.

- Parents of Non-disabled Children:

- Initially parents of non-disabled children were reluctant to place their children within the same class with the disabled children but their attitude changed gradually. They were also satisfied with the present school system as they could share the distress of other parents about the children's problems.

Most of the parents expressed the desire to take initiative for vocational training for their children so that they can do different kinds of creative work.

| Parents | Views on the Current Situation Students' Class Performance and the System of the Inclusive School | Future Expectation |

|---|---|---|

| of Disabled Children | Satisfied - 100% | Vocational Training - 64.3% Further Education - 35.7% |

| of Non-disabled Children | Satisfied - 63.6% Unsatisfied - 36.4% |

Vocational Training - 18% Further Education - 82% |

Focal Group Discussion with Teachers

- Teachers of Inclusive Schools:

- Teachers expressed that the inclusive schools made the disabled children gain independence and become socially relaxed with the environment. Their observation was that both the disabled and non-disabled students were improving satisfactorily. Severely disabled children however required much individual attention, yet they also gradually became part of the inclusion group.

- Teachers of Regular Schools:

- FGD revealed that teachers of the regular schools had the knowledge about slow learners but they did not know much about disability. They expressed that it would be difficult for the disabled children to follow the curriculum of the regular class. Besides, most of the teachers expressed that they know nothing about the teaching method for disabled children. All the teachers demanded relevant training before starting of inclusive schools. After counseling and discussion, they agreed to help the disabled children though reluctantly, as they thought it was an additioned task to their regular workload.

| Teachers | Views Toward the CurrentInclusive School System | Future Expectation |

|---|---|---|

| of Inclusive Schools | Satisfied - 72.7% Unsatisfied - 27.3% |

Training Provided to Teachers - 68.6% Increase the Teacher - Student Ratio - 36.4% |

| of Regular Schools | Satisfied - 35% Unsatisfied - 65% |

Anxious About Future Success - 50% Positive with Teachers Training - 50% |

- Non-disabled Peers of Disabled Children in Inclusive Schools:

- The responses from the non-disabled classmates showed that they were happy to have disabled peers in the classroom. They felt encouraged to help one another in groups and at all the time as well. They felt that they were getting a new education and they wanted to help their friends when needed.

| Non-disabled Students of Inclusive Schools | Were able to develop friendship with disabled peers - 80% Could not understand their disabled peers - 20% |

|---|

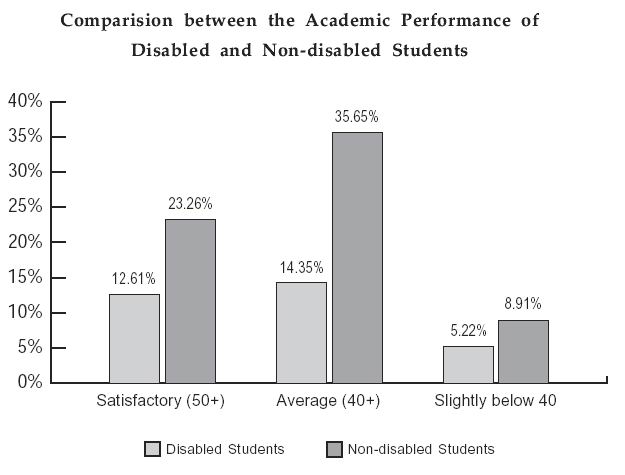

Evaluation of Academic Performance

The following table indicates the results of mid-term tests of all the seven "Inclusive Schools".

| Name of the School | Total No. of Disabled and Non-Disabled Students | Total No. of Disabled Students | Improvements Made by Disabled Students | No. of Non-disabled Students | Improvements Made by Non-Disabled Students | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satis-factory(50+) | Average(40+) | Slightly below 40 | Satis-factory(50+) | Average(40+) | Slightly below 40 | ||||

| Dhamrai | 88 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 76 | 27 | 41 | 8 |

| Savar | 49 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 39 | 10 | 23 | 6 |

| Kishorgonj | 77 | 25 | 9 | 14 | 2 | 52 | 16 | 30 | 6 |

| Norshingdi | 55 | 20 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 35 | 13 | 19 | 3 |

| Mirpur | 77 | 37 | 17 | 12 | 8 | 40 | 14 | 17 | 9 |

| Nabinagar | 57 | 22 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 35 | 13 | 18 | 4 |

| Faridpur | 57 | 22 | 6 | 13 | 3 | 35 | 14 | 16 | 5 |

| Total | 460 | 148 | 58 | 66 | 24 | 312 | 107 | 164 | 41 |

D

DDiscussion

According to the results obtained from the FGD with parents of disabled and non-disabled students, with teachers of "inclusive schools" and regular schools and with non-disabled students attending 'inclusive schools', it was evident that inclusive schools are having a positive impact on changing the attitude of the society at large.

FGD with Parents:

The parents of the disabled children were happy to be able to send their children to mainstream schools as they felt that by this approach the barrier to "inclusion" could be eliminated. Moreover by observing the success of their own children, they are able to start anew looking for the abilities rather than disabilities of their children more realistically (Table IV).

The parents of non-disabled children although hesitant in the beginning to allow their children to go to school with the disabled children, later had their attitude changed as they found that their children were happy to mix with the disabled peers with a helping attitude (Table IV).

FGD with Teachers:

The FGD with the teachers of inclusive schools revealed that there was much improvement in terms of independence, sociability as well as academic performance among both the disabled and non-disabled students. Therefore, teachers were willing to integrate not only the mildly disabled but also the severely disabled children in the mainstream schools with some individual attention (Table V). The teachers of the regular schools however were doubtful about their own capability of handling the disabled children. They demanded training prior to starting of any inclusive schools. It was also revealed from the FGD with teachers of regular schools and inclusive schools that once the teachers were exposed to dealing with all the children (i.e. disabled and non-disabled), there was a definite change in attitude. Surprisingly the difficulties in relation to disability disappeared and the teachers started "seeing all children as children" (Table V).

FGD with the Non-disabled Students:

The FGD with the non-disabled students of inclusive schools revealed that most of them expressed positive attitude towards the disabled peers. The school system also introduced partnership between a disabled child and a non-disabled child as "peer partner". The non-disabled children were happy to know about the disabled children and felt it was a learning experience for them. All of them regarded it as their duty to help as they were part of the peer groups. Besides, the non-disabled children are found to have spontaneously helped their disabled peers in the classroom. Sometimes they even took turn to help them feed or take them to the toilets, or help clean their drooling mouths with handkerchieves. The "peer partnership" was proved to be very successful (Table VI).

Evaluation of Academic Performance

The results of the mid-term and other class tests administered to all the children (disabled and non-disabled) revealed satisfactory performance of both two groups of students (Table VII). Surprisingly quite good percentage of disabled children had satisfactory and average performance. These seven inclusive schools as pilot schools should be served as an 'eye opener' for the government schools and schools run by NGOs. In a number of developing countries including India, children with disabilities have already been integrated into mainstream schools. In 1986, the National Policy on Education of India had included children with moderate disabilities as far as possible in the mainstream schools. In practice children with multiple and severe disabilities have also been integrated into the UNICEF assisted "Project Integrated Education for the Disabled" (PIED). However, prior to any such integrated school programme, teachers training either as pre-service or in-service is highly recommended (Jangira 1995). In fact, the philosophy of "Education For All" or "Inclusive Education" implies improving the learning achievements of children through the effective schools for all initiatives. The District Primary Education Programme (DPEP) funded by the World Bank in India has been running effectively in most of the states that in-service training for teachers is regarded as crucial to its success (Jangira, 1995).

In Bangladesh the Save the Children Alliance, BPF and UNICEP have been collaborating with UNESCO in spreading awareness regarding "Inclusive Education" among educationists and policy makers. The government needs to be sensitive about this issue so that a great stride can be made if all government schools are made "schools for all".

Last but not the least, the positive attitude of donors in this regard also makes a lot of difference. The pilot schools of BPF are funded by 'Job Placement' in Australia. The sharing of ideas in terms of including the excluded from education and stretching their helping hand has gone a long way in the success of this programme. More such partners are welcome to take forward this ideology.

References

- Ainscow, M. (1993) 'Teacher Education as a strategy for developing inclusive schools', in R. Slee, (ed.) Is there a desk with my name in it? Politics of Integration. London: Palmer.

- Jangira, N.K. (1995) 'Rethinking Teacher Education', Prospects, Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, UNESCO, June.

- Jayachandran, K.R. (2000) Possibility of Inclusive Education in India based on Success of Integrated Education in Kerala State, India, Paper presented in the International Special Education Congress held in Manchester, July.

- Nanjundaiah, Manjula (2000) Shift from Rehabilitation to Inclusion: Implementation of Inclusive Education (IE) through Rural Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) Programme of Sevain- Action, India, paper presented in the International Special Education Congress held in Manchester, July.

Salamanca Statement and Frame for Action on Special Needs Education, Salamanca, Spain, 1994.