Attitudes to Women with Disabilities in Japan:

The Influence of Television Drama

Arran Stibbe

Associate Professor, Chikushi Jogakuen University

Japan

Abstract As Marshall (1998) points out, traditionally disabled women have been marginalised and invisible in Japanese society, often hidden away by shame-filled relatives. However, over the last ten years, there has been an unprecedented increase in disabled female characters appearing in television dramas. These dramas portray disabled women as attractive, gainfully employed and successful, albeit often due to the influence of a non-disabled male character. This article explores the extent to which these television dramas have inspired the imagination of the Japanese youth who watched them during their formative years. A case study was carried out where 50 Japanese university students wrote compositions about fictional characters, both disabled and non-disabled, of both genders. These 200 compositions are compared across gender and disability lines, and correlated with features of the TV dramas.

Introduction

The remarkable findings of Hanna's (1986) free association experiments to determine attitudes to disabled women among college students in America continue to be quoted in literature about disability to this day. Asked to write down verbal associations with the word 'woman', students wrote down words associated with sexuality, careers and motherhood. For 'disabled woman', these themes were largely absent, and instead, replies included 'crippled', 'wheelchair', 'grey', 'old' and 'sorry' (reported in Out, 1987). This left an image of disabled women as 'sick and feeble, grey and old, childless and sexless' (Hanna and Rogovsky 1991, p.55). In addition, when asked to imagine a male and female disabled person and give the cause of their disability, the cause attributed to the man tended to relate to war, sports, driving automobiles, and other active causes whereas the cause of the woman's disability was more likely to be attributed to passive factors, for example illness or careless accidents (Hanna and Rogovsky 1991, p.55). Commenting on these results, Morris (1991, p.97) writes that 'the overwhelming association with disability for women, as these students' reactions show, is one of passivity, dependency and deprivation'.

Attitudes to disability are particularly important in Japan, where disabled people, and people who are different from the majority in some other ways like being gay or foreign, often find it hard to gain social acceptance. In the words of Marshall (1998), disabled people have traditionally been 'an invisible, impotent group, hidden away by shame-filled relatives'.

However, recently the visibility of disabled women has been raised by a large number of popular television dramas, as analysed by Stibbe (2001), which revolve around disabled female characters. These TV dramas break traditional stereotypes of disability by portraying disabled women as attractive and engaged in relationships with men, as well as involved in productive employment, both symbols of acceptance within Japanese society. However, as described by Stibbe (2001), in some areas the TV dramas follow traditional stereotypes, portraying disabled women as dependant on non-disabled males, and failing to address the social and environmental factors which disable individuals in contemporary Japanese society.

The research questions explored in this study are: a) To what extent do young people in Japan cling to traditional stereotypes of disabled women as unattractive, unemployable, marginal members of society? and b) To what extent are they influenced by the television dramas they have watched?

Methodology

The Methodology used by Hanna (1986) involved asking 181 undergraduate students to write down what came to mind when they heard the phrase 'disabled women'. In many cases the students could think of nothing and left their papers blank. This, in itself, could be interpreted as reflecting the invisibility of disabled women in society, or it could, however, show a limitation of the experimental design. It is clearly an artificial task to write down one or two words in a limited time to sum up something as complex as attitudes to disability. In the second methodology Hanna (1986) used, students were asked to carry out a more feasible task, imagining a disabled man and woman and attributing the causes of their disabilities.

However, in addition to the causes, there are many other features that the students could have attributed to their fictional characters, such as physical appearance or employment, which could have highlighted important aspects of the students' perceptions of disability. With this in mind, a methodology which required students to invent fictional characters and attribute a wide range of characteristics to them was created. Fifty Japanese university students were asked to invent 4 fictional characters: a non-disabled woman, a non-disabled man, a disabled woman and a disabled man, and write a full length essay about each character. The differences between the description of disabled women and other characters were assumed to reflect the students' perceptions of the images of and their attitudes towards disabled women.

The exercise was conducted as part of a creative writing course, and fitted the pedagogical aims of the course. One of these aims was to encourage creativity through understanding cultural stereotypes, and empower students to move beyond these stereotypes if they so wished. The advantage of conducting the study within a writing course was that students could be given detailed instructions on the structure of the essay. One disadvantage was that the students, who were all English majors, wrote in their second language, English, rather than their native language. Detailed discourse analysis was therefore not possible, but analysis of the themes and content of the essays was carried out.

The students were given the pattern as illustrated in figure 1 to follow when writing the essay. The pattern involves a fictional character being described in the introduction, then a significant event, described in the body and followed by a conclusion stating what eventually happened. This structure was selected because it encourages the students to attribute a number of features to the characters, such as job and appearance, but gives them freedom to describe more features if they wish. The conclusion elicits what students see as a 'solution' to the 'problem' of being disabled in Japanese society. The 200 essays (50 essays about each of the four characters) were then content-analysed, both qualitatively and quantitatively and compared with the story lines appearing in the TV dramas.

Figure 1 The pattern that students were asked to follow in writing their essays

- Introduction

- Before - describe background information about what kind of job the character does, what he /she looks like, his/her personality, where he/ she lives, his/her hobbies, dreams, etc.

- Body

- During - describe something significant that happens to him/her. Start this paragraph with 'One Day...'

- Conclusion

- After - summarise the first two paragraphs very briefly, then say what happened eventually, what the future will be after the event, etc.

D

DResults and Discussion

Nearly all the students managed to come up with a story that more or less fitted the assigned pattern. There were just three students who failed to create a fictional character at all, instead they described incidents from their own lives when they encountered a disabled woman on a bus, train and in a restaurant respectively. These three accounts all showed some fear or embarrassment. The student on the train was 'too frightened to speak or move' when the disabled woman tugged at her skirt. The student on the bus was 'a bit scared of sitting by her', and the student in the restaurant was 'not brave enough to help' the disabled woman who was having problems in ordering her food. When questioned further, all three students said that they had never seen any dramas in relation to disabled people on TV.

Dramas featuring disabled women in the leading role are popular in Japan, particularly among the age group of the students, and most students had seen at least one drama series featuring a disabled woman. The average number of series watched was just under 2, and there were about 12 episodes per series, so the average number of episodes seen was around 24. The following sections describe aspects of the students' compositions and compare them with features of the TV dramas.

Appearance and Sexuality

Shakespeare (1996,1997) reveals how people within western culture ignore the sexuality of disabled people, and how they fail to consider disabled people as desirable potential romantic partners (see also Kent, 1988; White, 1997). The 'sexless stereotype' (Golfus, 1997) is perhaps particularly applicable to Japan where disabled people have traditionally not been considered as suitable romantic partners. One student wrote the following about Ototake Hirotada, a disabled celebrity: 'He married recently. Honestly, I thought he couldn't get married. But he did. I am always surprised by him.'

Recent TV dramas have, however, been breaking the sexless stereotype by casting beautiful, popular actresses in leading roles to portray disabled women being engaged in successful relationships. The question is, to what extent do the students essays reflect the trend of portraying disabled women as attractive?

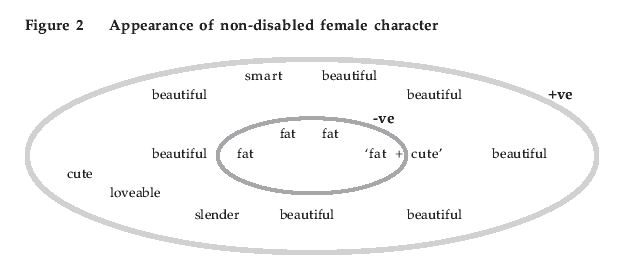

Figures 2 and 3 show a comparison between the attributions of physical appearance to non-disabled and disabled female characters (respectively) in the students' essays. The inner circle contains attributes typically considered as negative in Japanese culture and the outer circle shows positive attributes. All of the words describing appearance in every essay are reproduced in the diagram, and where one student gave more than one word, they are listed separated by a '+'. Attitudes to Women with Disabilities 21

D

DAlthough specifying physical appearance was suggested, only 15 students actually described the physical appearance of the non-disabled women. There is a clear pattern within these results, with the exception of the attribute 'fat', all attributes were positive, including beautiful, slender, loveable and cute. On the other hand, figure 3 shows the attributions of appearance to the disabled female character. In this case only four students mentioned the appearance of the disabled woman.

D

DAll 50 students described the disability that the woman had, yet only 4 described her appearance, suggesting that disability is more relevant than appearance. Three of the four students did write about beautiful disabled characters, and they might have been influenced by the 4, 3 or 2 (respectively) dramas they had seen. But that leaves 33 students who watched up to 6 series of disability dramas about beautiful disabled women, were not influenced sufficiently to mention the appearance of their characters.

When it comes to finding a partner, there was a wide gap between disabled female characters and their non-disabled counterparts. Among the stories about disabled women, only 7 eventually found husbands or boyfriends. However, for the non-disabled women, more than twice as many stories (15) conclude with finding an ideal lover or partner. This is contradictory to the fact that success in finding a romantic partner is central to all the TV dramas. The situation is even more extreme for men: 11 stories about non-disabled men ended in having wives or girlfriends, whereas only 4 stories about disabled men concluded with having partners. This is summarised in figure 4:

| Disabled Women 7 | Non-Disabled Women 15 |

| Disabled Men 4 | Non Disabled Men 11 |

These results indicate very little willingness for the students to portray disabled women as attractive and capable of finding a partner. This suggests that if the TV dramas are having an effect on the imaginations of the students, they are affecting only a small number of those who have watched them.

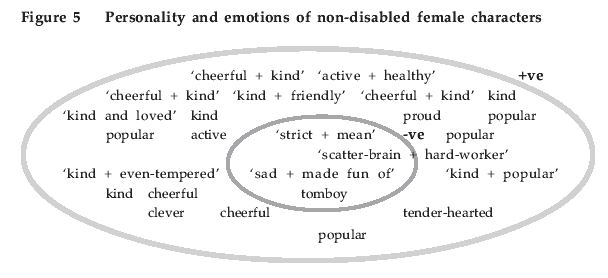

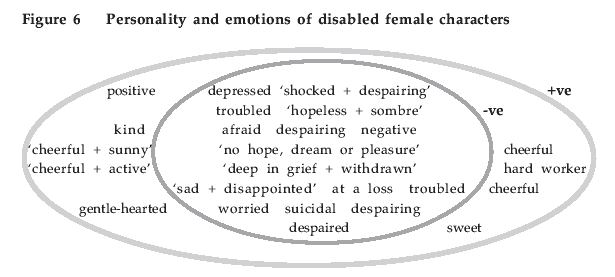

Personality and Emotions

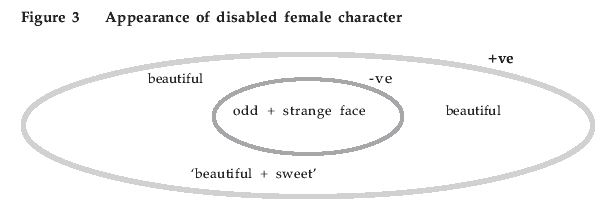

While differences in descriptions of appearance were quantitative, there is a large qualitative difference in attribution of personality and emotions between disabled and non-disabled women. As figure 5 shows, the attribution of personality and emotions to non-disabled female characters was mostly positive, the most common being kind (10), cheerful (5), and popular (5).

D

DFigure 6 shows the very different attribution made to the disabled female characters.

D

DThe vast majority of attributions for personality or emotions for disabled female characters are negative, describing the depression, despair, worry and grief of being disabled. Four students did use the word 'cheerful', although one of them wrote 'although she had a handicap she was cheerful'.

The most striking difference in these results is that for non-disabled women, the most common attribution was kind, whereas only one disabled woman was described this way. This suggests a particular orientation towards disabled women as receiver, rather than giver of kindness. In addition, while 5 non-disabled women were described as 'popular', none of the disabled women were described that way.

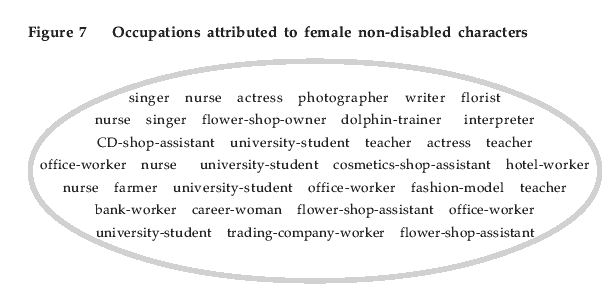

Jobs

As shown in figure 7, 34 students mentioned the occupation of the non-disabled female characters. On the whole, the kind of jobs mentioned are typically done by women in Japanese society such as nurse, office worker, and shop assistant. Only a few had higher status jobs including a shop owner, dolphin trainer, famous interpreter and teacher.

D

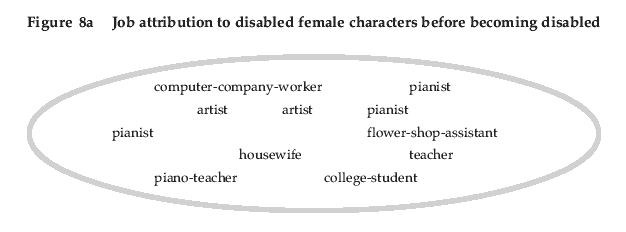

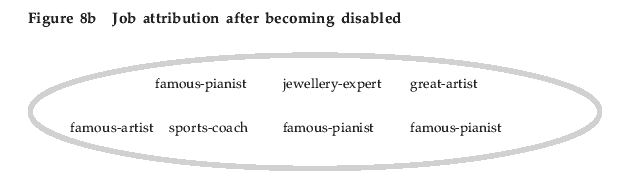

DThe job attribution for disabled women is described in figure 8. This figure is split into two diagrams because many stories described a woman who was not disabled at first, but who became disabled during the course of the story.

D

D D

DOnly 14 students made some kinds of attribution of jobs to disabled female characters. Of these, the majority described the jobs the characters had before becoming disabled. In these stories, the woman then became disabled and either the work was not mentioned again, or the character suddenly became talented and famous.

Nearly all the jobs explicitly attributed to disabled women were 'special' jobs, requiring outstanding talent, as opposed to the 'normal' jobs attributed to non-disabled women. This shows an inability to imagine a disabled person who is not outstandingly talented as involved in productive employment. This stands in contrast to TV dramas, in which disabled female characters nearly all have regular jobs, including a wheelchairusing librarian, a deaf nurse, a deaf office-assistant and a blind flower shop assistant.

The disregard of disabled women's employment can also be seen in the conclusion. For disabled women, 7 stories ended with a job-related conclusion, but more than twice as many stories about non-disabled women (15) ended that way. This can also be seen in the conclusions for disabled men (figure 9).

| Disabled Women 6 | Non-Disabled Women 15 |

| Disabled Men 11 | Non Disabled Men 16 |

Cures and Other Resolutions

One of the strongest points of criticism of fiction in the west is that stories about disabled people frequently result in a 'cure' climax, where the unhappy disabled person becomes cured and lives happily ever after (Darke, 1997, p.37). This is the 'medical' model of disability (Pointon and Davies, 1997, p.1), which assumes that 'the impairment or condition the person has is the key problem'. In contrast, the 'social model' emphasises social and environmental factors such as prejudice and physical barriers that disabled individuals (Karpf, 1997, p.80). The task ? writing a story following the structure 'introduction, body, conclusion' ? was designed to force the students to create some kind of resolution, showing whether they think about disability in the way of the medical or social model.

The 'cure' climax is rare in the TV dramas, yet in the present study, 8 stories for disabled women and 7 stories for disabled men ended with some kind of cure. The most common resolution involved sports, however, with 9 female and 8 male characters transformed through sports. This is no doubt due to the large amount of media coverage of the Nagano paralympics in 1998.

The female characters became: a famous wheelchair tennis player, a wheelchair basketball player, a paralympic swimmer, a wheelchair marathon winner, etc. This 'overcoming all odds' scenario is, however, also part of the medical model, since 'within this perspective, it is not society which disables someone...but the individual who either fails to 'rise above' their misfortune or exhibits the personal strength and willpower to achieve' (Morris, 1991, p.101).

In most (17) of the other endings, the disabled women are 'saved' by men, either through their help or love. Again, this is the medical model, since the problems of being disabled can be solved internally, within the character, through a change of emotions brought about by the male characters, rather than through societal change.

Although there were a total of 43 happy endings or resolutions for disabled female characters, and 42 for disabled male characters, not one transformation occurred through changes in the social and political environment. This suggests that the social model, which is slowly changing attitudes to disability in the west, has not yet influenced the imaginations of the students in this study, despite movements like the Ototake's (1998, p.225) barrier-free campaign.

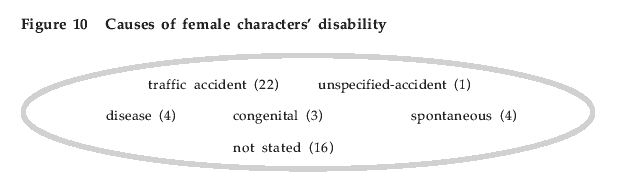

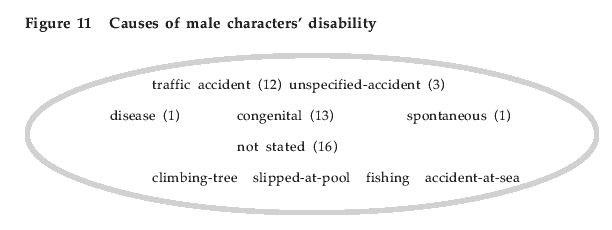

Attribution of Causes of Disability

As mentioned above, Hanna and Rogovsky (1991) found that students attributed men's disabilities to external factors where the characters were involved in active tasks, such as war or sports, whereas for female characters, the causes were carelessness or illness. This is different from the pattern of attribution of Japanese students, which is illustrated in figures 10 and 11 (the number of cases (stories) is given in parenthesis in these diagrams).

D

D D

DThe most important difference between male and female disabled characters is not one of active/passive but congenital/accidental. Thirteen male characters were disabled from birth, something beyond the characters' control, compared with only 3 female characters. For the other female characters, most of them became disabled through accidents. The cause of these accidents was often left unspecified, but 7 of the students wrote 'on her way to/coming home from school/work'. Being careless was the general impression: one wrote 'concentrating on other things'. Two accidents involved cars, but in both cases the woman was not driving, leaving all causes of disability for women either unspecified or passive.

The attribution to disability for male characters was a little more active, like tree climbing or fishing, but there were only 4 cases like this. Where specified, the traffic accidents were the same as the female characters, i.e., on the way to work or school, with no examples of the male characters driving either.

In general, the causes of both male and female disability were mostly passive, but data from the non-disabled male character contrasts with this. Within this data there happened to be 5 accidents, all of which involved definite action by the male character - one hurt his muscles in hard baseball practice, one slipped over when riding a motorbike, one had an accident while operating machinery, one braking to avoid a dog, and one hurt his arm in rescuing a woman. This suggests that the important division is disabled/non-disabled rather than disabled man/disabled woman.

Conclusion

This study is designed to investigate the attitudes of young people towards disabled women in Japan, using a sample drawn from university students. By asking the students to write essays about disabled and non-disabled characters of both genders following an identical pattern, similarities and differences between descriptions across gender and disability are found.

Several major differences are identified in the descriptions. Firstly, a number of non-disabled women are described as beautiful, but only a handful of students describe the physical appearance of disabled characters. Secondly, more than twice as many stories about non-disabled women end with finding a partner as compared to those of disabled women. Thirdly, the personality and emotions of non-disabled women are described mostly in positive terms, while disabled women are described as depressed, despairing and grief-stricken. Fourthly, many non-disabled women are described as 'kind' or 'popular', but only one disabled woman is described this way. Finally, the majority of non-disabled women are described as having regular jobs, but very few disabled women's jobs are mentioned, and these involve outstanding talent.

These facts indicate that the students in the group have difficulty in imagining disabled women in the roles of attractive partner, giver of kindness, popular member of society, or employed person. Instead, disabled women are portrayed as receivers of kindness, often by men, who solve their problems for them. The positive messages of the dramas - that disabled women can be attractive partners and can be involved successfully in normal employment seem not have reached the students yet. Instead, echoes of the negative messages contained in the dramas can be seen in the students' essays ? in nearly all dramas the disabled women are not givers of kindness but need to receive it from men, who transform their lives (Stibbe 2001).

In the students' essays, the disabled female characters' lives are often transformed through becoming extraordinary, for example becoming a famous artist or paralympic swimmer. However, Marshall (1998) points out that 'the way people who are overcoming their disability in a very obvious physical manner are treated and the way ordinary disabled people are treated [in Japan] seems very different'. She calls for 'appreciation for all people with disabilities, whether or not they can ski down a mountain'. The focus on 'overcoming all odds', as well as cure, and transformation through the love of men all follow the medical model, showing a lack of awareness of the social and environmental components of disability.

These students are part of the generation who will be the furture leaders of Japan. If the rights of disabled people are to be protected in Japan in the future, leaders will have to understand the social model of disability and discard traditional negative stereotypes. The TV dramas are just beinging to eliminate some of the worst parts of the stereotypes, but assuming that viewers in general are like the 50 students taking part in this study, the dramas have not yet influenced the imaginations of their viewers in a positive way.

References

- Darke, P. (1997) 'Eye witness', in A. Pointon and C. Davies (eds.) Framed: Interrogating disability in the media. London: BFI Publishing.

- Golfus, B. (1997) 'Sex and the single gimp', in L. Davis (ed.) The Disability Studies Reader. London: Routledge.

- Hanna, W. and Rogovsky, B. (1991) 'Women with Disabilities: Two handicaps plus', Disability,Handicap and Society, 6:1, p.49-63.

- Hanna, W. (1986) Women with Disabilities: Free associations and attributions (unpublished manuscript).

- Karpf, A. (1997) 'Crippling Images', in A. Pointon and C. Davies (eds.) Framed: Interrogating disability in the media. London: BFI Publishing.

- Kent, D. (1988) 'In Search of a Heroine: Images of women with disabilities in fiction and drama',in A. Asch and M. Fine (eds.) Women with Disabilities. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Marshall, N. (1998) 'Hidden Truths', in Being A Broad (on-line). http://www.beingabroad.com/mayjune/html/body_hidden_truths.html

- Morris, J. (1991) Pride against Prejudice. London: Women's Press.

- Morris, J. (1997) 'A Feminist Perspective', in A. Pointon and C. Davies (eds.) Framed: Interrogating disability in the media. London: BFI Publishing.

- Ototake, H. (1998) Gotai Fumanzoku. Tokyo: Kodansha.

- Out (1987) 'Out of Sight Out of Mind', Disability Rag, Jan/Feb. p.11.

- Pointon, A. and Davies, C. (eds.) Framed: Interrogating disability in the media. London: BFI Publishing.

- Shakespeare, T., Gillespie-Sells, K. and Davies, D. (1996) (eds.) The Sexual Politics of Disability. London: Cassell.

- Shakespeare, T. (1997) 'Soaps: The story so far', in A. Pointon and C. Davies (eds.) Framed: Interrogating disability in the media. London: BFI Publishing.

- Stibbe, A. (2001) 'The Portrayal of Women with Disabilities in Japanese Television Drama',Bulletin of the International Cultural Research Institute of Chikushi Jogakuen University, 12.

- White, R. (1997) Invisible Women: Social stereotypes about women with a physical disability. Unpublished paper. DePaul University.