Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For , By and With Disabled Persons

Part One

THE PURPOSE OF SPECIAL SEATING:

Freedom and Development, Not Confinement

CHAPTER 7

Listening to Rufina Listen to her Body

Learning from a Young Girl with Athetosis How to "Listen to Her Body, " to Help Her with Control for Sitting and Moving

RUFINA is a bright little girl with athetoid cerebral palsy. She was brought to PROJIMO from Mas Validos, a community rehabilitation program in the state capital. (Mas Validos was started in 1985 by two disabled youths who had gone to PROJIMO for their own rehabilitation, and then stayed for a year to apprentice as rehabilitation workers.) Rufina was accompanied by two social workers, but no family members. Her parents are poor migrant farm workers who dared not request time off, for fear of losing their seasonal jobs.

When Mari asked Rufina how old she was, the child shook her head. But she looked about 7 or so. Rufina , is shy, yet she has a ready smile and a stubborn will. Although she understands language well, her difficulty with mouth and tongue control make her speech hard to understand. She does her best to communicate using sounds, signs, and gestures.

The girl's physical ability is quite limited due to spasticity combined with athetosis (uncontrolled movements which keep her body and limbs twisting and writhing). She came to PROJIMO in a bright red wheelchair that had been donated by a charitable organization. In her adult-sized chair, her body's continuous strong thrusts into extension (arching backwards) made it a never-ending battle for her to stay in the chair and not pitch off of it.

Rufina has strong hands and can grip things fairly well. However, she had been delayed in developing manual skills, because her hands were constantly kept busy trying to make her uncooperative body stay inside her wheelchair. Because of this, she was unable to feed herself, or to use her hands for play or other activities, making her almost completely dependent on others for all of her needs.

A SERIES OF TRIALS AND ERRORS

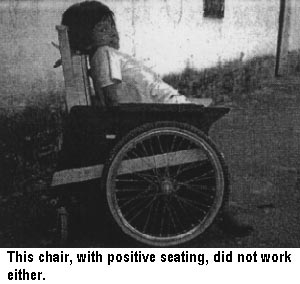

The PROJIMO team observed Rufina's difficulties in her huge wheelchair. Their first suggestion was to seat the girl in a child's wheelchair of the correct size for her body.

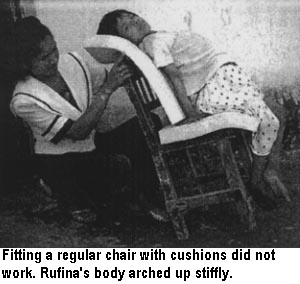

Another idea was to fit her wheelchair with an insert so she could sit with her hips at a 90degree angle. They tried each of these adaptations, together with various hip, belly, and chest bands. Also, they put a raised pad on the front half of the seat to try to keep her from scooting forward when her body stiffened.

Altogether, the team tried over a dozen different kinds of seating, strapping, and angles of tilt.

Nothing seemed to help.

With each of these trials, they asked Rufina whether she thought the adaptation helped her to sit better or made her more comfortable. Each time she emphatically said NO. She made it clear that she felt better and more in control in her big red wheelchair. At first the team thought she was just afraid to try something new ... or that she was emotionally attached to her handsome (if inappropriate) first wheelchair.

But, on observing the girl carefully, the team realized that all the adaptations they had tried only seemed to make her body movements worse. The hip and body straps triggered such forceful thrusting that they were counter-productive. Her body used up so much energy pushing against the restraints that she streamed sweat and quickly became exhausted.

With each new trial, Rufina insisted that she preferred her own wheelchair. The team knows how important it is to listen to a child and to respond to her wishes. And, reluctantly, they had to agree that none of their improvisations helped. Inadequate as the huge wheelchair was, they had found no better alternative. They were almost ready to give up and let Rufina continue her struggle to keep upright in her beloved chair. But that was a shame, since it did not let her use her hands for other activities.

Then the team had one last idea. They saw that one problem with the giant wheelchair was that Rufina's right knee hooked over the front edge of the seat, pulling her forward.

|

This caused her to push herself backwards, and to start to slip out of the chair, a process that she was constantly having to fight.

|

So they tried one last experiment: a long, padded board, placed on the seat, to extend her legs straight forward.

|

"So how do you like it now?" Mari asked her, expecting the same negative response. But this time Rufina smiled and said: "It's better!"

Indeed, she was able to sit up straighter and seemed to have more control of her body and hands.

This time, when they experimented with a fairly loose body-band, her body appeared not to fight it as much. And Rufina agreed that it helped.

Rufina takes the lead. Excited by her new ability to sit upright for moments without struggling, Rufina took the problem-solving initiative. Now that her hands were freer, she could experiment to improve her stability. Leaning forward, she grasped her left foot and, with a lot of effort (but insisting that no one assist her), she doubled her left knee. The uncooperative leg kept trying to straighten, but the sponge padding on the seat-board helped to keep the bent leg in place. Then she caught her right foot, bent the knee, and tucked the foot under her left knee. This cross-legged position gave her better body and hand control than ever.

|

But one thing bothered her. When she crossed her legs, her knees pressed against the metal wheel-guards, under the arm rests. |

"Would you like us to remove the wheel-guards so that you can sit cross-legged more easily in your chair?" Mari asked her. Rufina nodded energetically. Within an hour, the panels under her armrests were removed, leaving more space for her knees. Now, Rufina could sit cross-legged more easily. |

More experiments. Next, the team worked on making a removable table for the wheelchair. They tried placing a standard table over the armrest. But Rufina rejected it - and with good reason. The table kept her from gripping the arm rests on her chair, which she still needed to do frequently in order to stabilize herself. So the team designed a narrower table that fit snugly between the arm rests. To the team's delight, Rufina was able to eat fairly well from a plate on the table, and even to pick up a glass of water and drink it without much spilling. |

Everyone was thrilled with the results, especially Rufina. The PROJIMO team was pleased, not only with her new comfort and ability, but with the key role the child herself had played in the problem solving process. Not only had the girl's participation led to better seating and improved function, it had also given her a new sense of self-confidence, equality, and personal worth.

Another Suggestion to Help Children Like Rufina to Sit Better

Before this book went to press, the author asked a number of persons with different disability-related skills to read the draft and make suggestions. No one took on this task with more care and concern than Ann Hallum, an instructor of physical therapy who has made several teaching visits to PROJIMO. (Ann is one of those rare teachers who treats her students as equals, and challenges them to think problems through, rather than to just follow instructions.) She caught mistakes in the book, helped make points clearer, and had many good suggestions.

On reading about Rufina, Ann suggested a measure that she has found helps some children with athetosis (sudden, forceful uncontrolled movements of the body and limbs) to sit in a more stable position. Her suggestion is as follows:

USE OF A THIGH BAND FOR CHILDREN WITH ATHETOSIS

Ann explained that, instead of using a "pelvic band" (hip strap) to stabilize the hips, it sometimes works better to put the band across the thighs, close to the body. The "thigh band" often helps to prevent the sudden stiffening of the body that tends to make the child arch up, throwing her out of her chair. It pulls her backside down so that she sits squarely against her butt bones, which can help stabilize her in an upright, sitting position.

Rather than using a hip band (as shown in the pictures on the first page of this chapter), try using a thigh band, instead.

NOTE: For another example of changes (improvements and corrections) to earlier drafts of this book, see the two different versions of the exercise sheet for persons with an amputation of a leg, on pages 181 and 182.

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA