Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

PART FOUR

WHEELS TO FREEDOM

CHAPTER 36

Paraplegics Who Walk Where

Wheelchairs Won't Enter (India)

Innovations For, By and With Spinal-Cord Injured Persons in India

Centers for rehabilitation in the United States and many other countries encourage most spinal-cord injured persons to use wheelchairs as their primary way of moving about. Except for a few persons with low-level or incomplete injuries, walking is considered too difficult.

This emphasis on wheelchair riding with ease rather than walking with difficulty reflects the current trend in rehabilitation. The goal of maximum function is placed before normalization - even if this means doing some things "abnormally" (differently from how most people do them). Today, many spinal-cord injury self-help groups strongly encourage members to "Accept yourself as a wheelchair rider and get on with your life." Individuals are gently discouraged from putting a lot of hope or energy into "learning to walk again." Instead, they are urged to "join in the fight for accessibility and social acceptance of wheelchair riders."

I was, therefore, surprised by the approach of the rehabilitation center linked with the Christian Medical College in Vellore, India, which I visited in 1995 during a UN workshop on "Indigenous Assistive Devices for Disabled Persons." At the center, many paraplegic persons were being vigorously trained to walk with leg braces and elbow crutches.

Started in 1934 by a visionary woman doctor who was paralyzed in a car accident, the Vellore Center is recognized as the country's best, most comprehensive spinal-cord injury program. I was impressed, not only by the quality of services and innovativeness of activities, but by its human warmth and convivial spirit. The center's outstanding staff made a point of including disabled persons in the problem-solving process: as friends, co-workers, and equals.

Innovations at the center included a traditional village, complete with thatched huts and vegetable gardens. Here, disabled villagers lived and relearned the skills and the activities of daily living in a typical rural environment. We saw persons working and moving about there on crutches, or sometimes, crawling with knee-pads - but few used wheelchairs.

At first, I was concerned by the emphasis on walking rather than on wheelchair use. In recent years, India's government has launched a major program of wheelchair production. In cities, at least, increased attention is placed on wheelchair access (though there continues to be a huge unmet need).

I asked the Director: "Why such a strong emphasis on walking? Wouldn't it be more realistic to teach most paraplegic persons to use primarily wheelchairs?"

"Not at all!" he said. "Most spinal-cord injured persons who pass through our center come from remote villages, where wheelchair use is almost impossible.

"You will see for yourselves when we go to a village this afternoon."

He was so right!

Visit to an Independent Sugar-Cane Farmer Who is Paraplegic

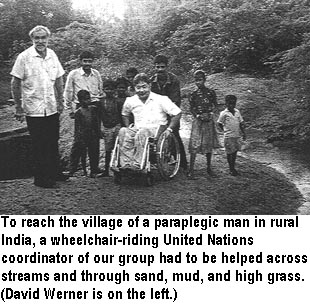

We visited a paraplegic man on the outskirts of a small village. To reach his homestead, we drove the last 2 or 3 miles over a narrow, muddy, rutted country road, difficult to travel even in a Jeep. For the last 200 yards, we had to travel by foot. We quickly realized the limitations of a wheelchair in such places.

On arrival, we made our way through a muddy field behind a large mud house. There we saw a man standing next to a small, rustic gasoline-motor-run sugar-cane mill. He was skillfully pushing armfuls of green cane into the rolling jaws of the machine. Helping him was a boy who, we learned, was his son. We had to look twice to realize that the man was disabled. He wore full-leg braces and arched his body backwards to stand and work with both hands, without having to support himself with his crutches.

RAM, the man at the mill, saw us approaching. He bounded over a pile of milled cane and greeted us warmly. He was dark, muscular, and had a look of uncrushable self-assurance. He appeared to be in excellent health (better than many people in India's hunger-ridden rural areas).

We observed Ram doing a variety of daily chores, ranging from clearing pathways to leading his cow to pasture across the narrow dikes of a rice field. Totally self-sufficient, he provided for his wife and children through his own hard physical labor. He had the innovativeness of one who, since childhood, has lived in a difficult environment where dexterity and creative ingenuity are essential skills for staving off hunger and for survival.

A pit latrine. Ram's innovations included a pit latrine with a wooden toilet seat (unusual for rural India, where the custom is simply to squat). He had built it next to a cement-covered mud-brick water trough. (The pit was over 2 meters deep, in order to avoid contamination of the surface water that fed the trough, which ran through a shallow ditch from a spring, 200 yards away.)

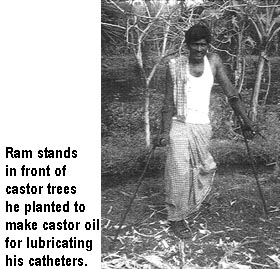

Home-grown castor-oil catheter lubricant. Ram had also found a way to catheterize himself at low cost. Like most spinal-cord injured persons who lack normal bladder control, to drain out urine he needed to pass a catheter (clean rubber tube) through his penis into his bladder every few hours.

Rubber catheters can be cleaned and reused hundreds of times (see Chapter 25, on catheterization). But for each use, they need to be lubricated (oiled). And commercial medical lubricants - such as KY Jelly - are expensive.

To save money, Ram had stopped using costly medical lubricants and had begun to use castor oil. But he soon learned that commercial castor oil was contaminated, causing repeated urinary infections. So he planted his own castor trees, harvested the beans, and pressed them carefully under clean conditions to extract the oil. With this clean home-made oil, he explained, he now had almost no problems with urinary infections.

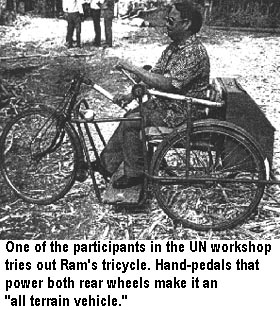

A two-rear-wheel-drive tricycle. For most of his farm work, Ram moved about with full-leg orthopedic braces and crutches made at the rehab center in Vellore. But for travel into town, he used an "all terrain tricycle" that he had designed and built with help from a local welder.

Most hand-powered tricycles made in India have front-wheel-drive, and they are therefore useless in mud and sand. The front wheel has little traction and tends to slip because the person's weight is mostly over the back wheels.

But Ram's tricycle was different.

Ram's tricycle has 2 hand cranks (adapted bicycle pedals), one on either side. With bicycle chains and sprockets, they power both back wheels.

The steering mechanism consists of a bar extending back from a bicycle fork that holds the single front wheel. When traveling on a fairly hard, flat roadway, Ram can steer with one hand and pedal the chair with the other (one wheel drive). For two-wheel-traction in mud or sand, he can pedal with both hands. But that means he must let go of the steering rod.

In order to keep the chair moving ahead in a straight line when he is not holding the steering rod, Ram improvised a spring device on the steering shaft of the front wheel fork. (See photo on left.)

The 2 springs persistently push the front wheel into a straight position. When Ram comes to a curve in the path, he lets go of one pedal just long enough to get around the curve. When he lets go of the steering rod, the front wheel automatically straightens.

Another advantage of this two-hand rear-wheel-drive tricycle (compared to one-hand-drive ones) is that for long distances it is less tiring to use. The rider can provide power with both arms at once, or use only one arm while resting the other.

(For more ideas on hand-powered tricycles, see Chapter 31. For a "4-wheel drive" all-terrain tricycle, see the drawing at the bottom of page 343.)

Observing the innovative problem-solving skills of rural disabled persons like Ram made a deep impression on the visiting rehabilitation specialists and technicians. By the end of the 10 day workshop, many declared they would work more as "partners in problem solving" with disabled clients, and encourage them to design or improve upon their own devices and solutions.

The visiting professionals gained greater respect for the creativity and abilities, not only of disabled people, but of poor, unschooled, disabled people. And that was a big step forward.

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA