Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

Part Five

INNOVATIVE METHODS AND APPROACHES

CHAPTER 40

Ways Disabled Persons Win Community Respect

Making Unusual Abilities Available. Many persons with disabilities have outstanding abilities. One of the best ways that disabled persons can win the respect and appreciation of those around them is by making their particular abilities visible or publicly available. Here are a few examples.

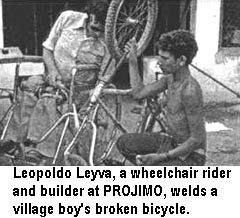

Welding service and repair shop. Several of the disabled workers at PROJIMO learned welding and metal-working skills in order to build wheelchairs. Because there is no other welding shop in town, farmers began to come to them with broken plows, boys came with broken bicycles, and women arrived with leaking buckets. Completely unplanned, the wheelchair shop has become a village repair shop. People have come to see the disabled workers not in terms of their disabilities, but in terms of their ability to provide services that no able-bodied person there is able to do.

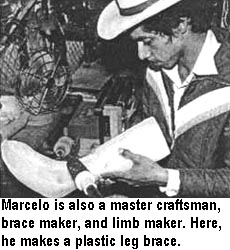

Unusual strength that comes from weakness. One time, when a street light in town burned out, the only person who was daring and able enough to change it was Marcelo.

Marcelo's legs are weak from polio. But his arms and hands are very strong because he has used crutches to get about on mountain trails since childhood.

Marcelo has won the respect of the PROJIMO team and of the villagers because he is a peace maker in times of dispute, a loving father to his four sons, and he does not waste his modest income on liquor, as do many of the village men.

A Christmas dinner for lonely old folks. A few years ago, when disabled youth at PROJIMO were planning a Christmas dinner, someone recalled that of the many elderly folks in town, some were abandoned and alone: "They must feel lonely on Christmas Eve. Why don't we invite them?" Everyone agreed. The occasion was a warm reunion, with music, stories, and lots of conviviality.

The old folks were touched that someone remembered them, as was the rest of the town. The villagers realized that, on this special day, the disabled group showed more social responsibility - more caring and sharing - than did the larger community. The disabled young people provided a good role model for all. Year after year, PROJIMO continues to invite old folks to Christmas dinner.

Courage in the Face of Repression

Abuse of authority in the Sierra Madre. In the mountains of Mexico, almost everyone fears the state police and the soldiers, who are often brutal to those who have committed no crime. One time, I (the author) had to help amputate the hand of a 10-year-old boy who was hit by a high-speed explosive bullet. Soldiers had fired at villagers at an outdoor dance. When someone shouted, "Here come the soldiers!" everyone ran in fear. So the soldiers fired at them. The logic: If they run, they must be guilty.

These were anti-narcotics troops, part of the so-called War on Drugs. The United States government supplies them with automatic weapons and high-speed bullets. (This violates international law, which prohibits use of such destructive bullets against civilians.)

Such brutality might be more excusable if the War on Drugs were not such a sham. The anti-narcotics troops are notorious for accepting bribes from the large drug growers. They do more to promote than to control the growing and trafficking of illegal drugs. I personally treated a man with broken ribs who was beaten up by the soldiers for not growing drugs.

When the US government demands from Mexico a "massive wave of arrests," the Mexican soldiers raid villages and drag men out of their homes at night. They divide their captives into two groups. They torture one group until they sign statements accusing those in the other group of drug growing. One time, those men and boys who refused to "confess" were thrown off the back of a speeding pick-up truck onto a gravel road. A friend of mine was still limping a year after this ordeal. In sum, the illicit drug scene and corrupt narcotics control program is a major cause of violence, death, and disability in the Sierra Madre.

Roberto and other disabled leaders of PROJIMO have publicly protested abuses by the soldiers and polioe, and have called on the Commission of Human Rights and on Amnesty International to become involved. Consequently, two of the disabled workers had their lives threatened. However, word of the abuses reached the President of Mexico, who gave orders that the drug-control troops cut back on violence. A period followed in which the worst violence, torture, illegal arrests, and clandestine killings were reduced.

Disabled women protect the village dootor.

The soldiers prohibit health workers from giving medical care to persons wounded by gunfire, and they are sometimes brutal with those who do. One time, four soldiers burst into the village health center and arrested Alvaro, a young doctor who had been a village health worker and who has worked closely with the PROJIMO team. They accused him of having provided emergency care to a man they were hunting and whom they had wounded. The soldiers marched Alvaro out of the clinic and threw him into the back of a pick-up truck.

The villagers, watching from behind closed doors, worried for the well-being and even the life of their doctor, but they were afraid to speak out. However, when word of the doctor's arrest reached PROJIMO, the team took action. In wheelchairs and on crutches, they surrounded the soldiers' truck, which was about to leave. The soldiers ordered them away. But the group refused to move until their doctor was released. The soldiers were taken aback. Reluctant to attack women in wheelchairs, they released the doctor.

As a result of this action, the disabled people at PROJIMO won even greater respect and appreciation in the village. As one of the village elders commented proudly, "What they lack in muscles, they make up for in guts!"

IN DEFENSE OF HUMAN RIGHTS

One cannot work for the well-being of poor and disabled persons without becoming involved in human rights and questions of social justice.

As an example, PROJIMO learned of a 12-year-old boy, ALEJANDRO, who one day in the slums of a coastal city asked a policeman, "What cailber is your pistol?"

"I'll show you!" said the policeman. Drawing his pistol, he shot the boy through the spine, paralyzing him for life.

PROJIMO has helped young Alejandro with medical care, schooling, skills training, and mobility aids (see Chapter 31). But the team has also tried to get legal recourse. They have not made a great effort to seek punishment for the policeman (which, given the existing power structure, is highly unlikely).

Rather, they have tried to get the city to assume responsibility for the boy's ongoing medical and disability-related costs so that he can stay healthy, attend school, and prepare himself for a reasonable life. It has been an uphill battle, but the city did respond with , limited assistance for a while.

More recently, the government's Integrated Family Development Program (DIF) has taken steps to improve the situation of Alejandro and his family, who live in dire poverty. This assistance was spear-headed by an outstanding social worker, DOLORES Mesina, who had polio as a child, uses a wheelchair, and is herself a graduate from PROJIMO. Dolores has helped to arrange scholarships for Alejandro to continue schooling, and found funding for a hand-powered tricycle, so that he can get to and from school on the rough roads.

Since Dolores assumed this important post with DIF, there has been much closer cooperation between DIF and PROJIMO.

In Defense of Disabled People's Rights. As a wheelchair-riding woman, Dolores Mesina has faced enormous obstacles. In Mexico, it is remarkable that she was able to persevere with her studies and earn a degree as a social worker. That she has obtained a key job in a government program for disabled people is a big breakthrough in the disabled community's struggle to gain strong representation in the decisions and services that affect them. Thanks to Dolores, the motto of the Independent Living Movement, NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT US, is a little closer to becoming a reality.

Dolores has also started and helped to lead an organization of disabled activists in the coastal city of Mazatlan. This organization has played an active role in the growing disability rights movement in Mexico, which has successfully pressured the Mexican government to adopt laws designed to guarantee greater equality, schooling opportunities, and employment of disabled people. Thanks in part to her effort, the barriers to schooling and employment may not be as great for the next generation of disabled youth as they were for Dolores.

In several countries, disabled people have succeeded not only in winning respect for their abilities, but they have won leading and decision-making roles in both government and non-government programs for disabled persons. Examples are Judy Heumann, a polio-disabled woman who now holds a high post in the Department of Human Services in the USA, and Beng Linguist, a blind Swedish activist who has a key position in the United Nations.

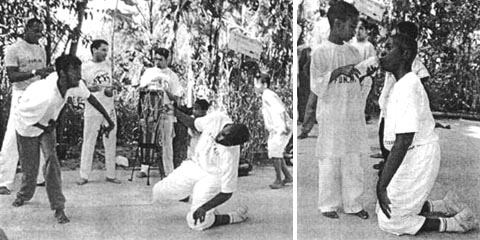

Disabled Children learn Capoeira in Brazil

FUNLAR, a community rehabilitation program in the favelas (slums) of Rio de Janeiro, includes disabled children in learning capoeira, a ritualistic form of self-defense. Here youths with developmental delay, Down's syndrome and cerebral palsy (boy on knees), perform to music together with non disabled street children.

Jesus Learns Karate at PROJIMO

Doug, a visiting North American who has cerebral palsy, teaches karate to Jesus, who has spina bifida and is visually impaired. (See Jesus' story, Chapter 45.)

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA