Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

Part Six

CHILD-TO-CHILD:

INCLUDING DISABLED CHILDREN

CHAPTER 46

An Unusual Friendship:

Manolo and Luis

Some of the best things that take place in a community based program, as in life, are completely unplanned. They take place because the program and its facilitators are flexible and relaxed enough to let spontaneity flourish and heart-felt adventures happen.

In this chapter we reprint an article from Newsletter from the Sierra Madre #20.* It is the true story about a unique friendship between two disabled young people at PROJIMO, as told by Oliver Bock, a California orthotist (brace maker) who has made several trips to the program to share his skills with village rehabilitation workers. The innovation described here is the way that persons with very different disabilities can complement and assist one another. It also raises the question of recruiting able-bodied but mentally handicapped young persons to be helpers or "attendants" of those who are able-minded but physically handicapped.

- ______________________________

- * The Nawsletter from the Sierra Madre is published 2 to 3 times a year by HealthWrights and covers innovations and ideas from community based health and rehabilitation programs in Mexico and elsewhere. It also looks at issues concerning the politics of health and the basic rights of disadvantaged and oppressed peoples, from both local and global perspectives.

Following the story, we give a bit of background about how Manolo joined PROJIMO and how another disabled child managed to reach him, when others could not.

Manolo and Luis

by Oliver Bock

Manolo feels caught. Once again, he doesn't know what to do. He is sure that a joke is being played on him, and he is confused. Lacking the tools for understanding, Manolo resorts to his tried and true response. "Don't look at me!" he demands. And, with a jerk of his head away from the insult, he trundles off, looking for more hospitable company.

Seeing Manolo retreat from the brace shop, sad-eyed Luis lets out his unmistakable cry. A throaty bellow and waving limbs draw Manolo to his side. Intuitively, Manolo deciphers the message that Luis needs company. Away from his family for the first time and having a hard time at making himself understood, after three days, Luis is somewhat desperate.

Manolo is gentle with Luis, but there are others who love to tease him. One of the favorite games they play with Luis is asking him if he misses his mother. Then his beautiful brown eyes look at you with wrenching sadness as his head drops into a crook of his elbow. With tears running down his face and arm, Luis sobs quietly until he is comforted.

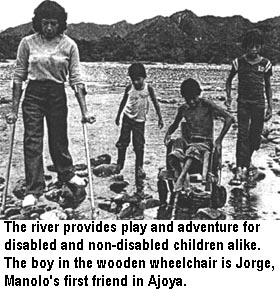

Manolo doesn't know how to play that kind of game, but he does know how to push a wheelchair. He is strong and enjoys pleasing his passenger. Luis loves going for rides, so the two of them head up the narrow path leading to the main street of Ajoya. It is a hot day. The mangos are almost ripe. The dust lifts easily, and quietly coats everything. The younger kids, almost impervious to heat, are playing, while the men tilt back against shaded adobe walls, waiting patiently.

The squeaking of dry bearings and a cloud of dust temporarily interrupt the magic stillness. Nearly indifferent eyes follow the pair as Manolo pushes Luis' wheelchair through the hot sun. Wheelchairs inhabited by all varieties of disabled bodies have become so commonplace in Ajoya that they no longer generate curiosity or fear in the villagers.

The overwhelming heat finally forces the two companions to seek relief. Manolo's round, soft body is shining with perspiration while Luis' angular, contracted body sticks uncomfortably to the vinyl seat and back of his chair. "Shall we go to the river?" Manolo asks hopefully. Luis eagerly agrees to the promise of adventure and escape from the oppressive heat.

With sweat streaming, the two companions make their way to the end of town and down the treacherous path toward the river. Boulders, erosion ruts, and deep sand turn the half mile into a monumental expedition. At times, Luis has to slide his spastic body out of his chair and drag himself over impassable obstacles while Manolo handles the progress of the chair. In one spot, Manolo has to carry Luis across a deep ravine, set him down on the far side, and then return for the wheelchair.

The patient determination of the two companions builds a feeling of friendship that is both wonderful and foreign to them. Twice Manolo asks Luis if he wants to abandon the mission. Both times, Luis answers Manolo with his deep expressive eyes, as if to say, "Let's go on. I know it's a lot of work for you and you must be tired, but I'm so excited. I love you for being able to take me with you like this." Manolo interprets the response correctly, and the two slowly labor on toward the river.

When they finally arrive, Manolo, hot and dusty, splashes into the slow-moving, tired river.

The small stream of water looks insignificant as it cuts its narrow path through the huge riverbed. Soon, when the rain comes, this calm trickle will become a raging torrent, at times filling the entire riverbed with a powerful flow of boulders, branches, and silt-filled water carried down from the high valleys of the Sierra Madre.

Manolo splashes his face with the tepid, green river water and looks upstream at the town he now thinks of as home. He can't remember how he got to Ajoya, but he knows it is where he is happy - happier than he has ever imagined possible. He thinks about the important jobs he has. He washes people who can't wash themselves and dresses them in clean clothes so that they can look nice. He fetches sodas for clever men who make amazing things in the workshops. Sometimes they even give him jobs in the shop, and that makes him feel very proud.

People like him here. Sure, they tease him, but he's used to that - and besides, here they tease with a smile. And those around him have problems, too. Many of them have bodies that don't work right. Some have shriveled legs and walk with crutches, and some sit in wheelchairs all the time and can't feel in their legs. There are others, like Luis, who can't control their bodies and have to live with twitches and jerks that keep them from talking or moving the way they want to ... For his part, Manolo has a good, strong body. He can help in a lot of ways, but his thinking doesn't work right. He doesn't understand many things, and he has a hard time remembering. But when something is clear, Manolo is happy to do it. He loves to write. He fills pages of notebooks with sentences that have been written for him to copy. He can't read and he doesn't know what he writes, but it doesn't matter. He is doing useful work!

A loud splash brings Manolo out of his thoughts. Luis has slid out of his chair and dragged himself into the river. Happily splashing away the heat and dust, he gives Manolo a huge grin. Manolo is a bit worried because Luis is wearing all his clothes and they are getting soaked. Luis smiles as if to say, "Its fine, my clothes are hot too." Manolo laughs and plops down in the river next to Luis. Luis splashes uncontrollably and Manolo imitates. The two friends are soaking wet and thoroughly enjoying the fruits of their difficult trek.

Across the river, on the bank overlooking the bathers, a wealthy landowner watches the scene. Sitting astride his horse, he contemplates the wheelchair. Watching the two friends, he realizes what a good thing it is that these children have a place to be where they can enjoy life and be valued for their ability to smile, laugh, play, and be helpful in whatever way they can.

Moved by a sudden impulse, the horseman spurs his beast down toward the two boys just as Manolo is lifting the joyous Luis back into his chair. Surprised and scared by the approaching rider, Manolo almost drops Luis and becomes confused about whether to run, fight, or remain still. Fear fills Luis' eyes as he senses Manolo's anxiety. With fewer options available, Luis sits and waits to see what will happen.

"Don't be afraid, my friends. I will not harm you." Manolo and Luis slowly look up at the horseman. He smiles at them and swings down off his horse. He is a small man, much smaller than Manolo, but he has the strength of someone accustomed to having power. "My name is Chuy. I was watching you two play in the water, and I thought you might like some help getting back to Ajoya." Manolo is uncertain. The friendly offer confuses him; he is torn between temptation and fear. Luis, on the other hand, is thrilled. His quick mind has already determined that he is about to get a ride back home. Manolo still can't make up his mind. Decisions are a threat to him, especially when they involve responsibility. Fortunately, Chuy resolves Manolo's confusion by helping Luis lift himself onto the horse.

Loading a spastic child onto a horse is no easy task, especially when the child is nervous and excited. Manolo quickly sees that his assistance is needed. Chuy is barely able to lift Luis, much less lift him onto the horse and try to pry his legs apart enough to straddle the horse's back. After several exhausting attempts, Luis proudly sits on the horse, with his hands tied together around Chuy's waist to keep him from falling off. When drool starts running down the man's back, he momentarily questions his generosity. But as they head back to Ajoya, with Luis groaning happily and Manolo gleefully pushing the empty wheelchair, Chuy feels glad that he decided to help.

Long shadows and cooling temperatures greet the trio as they enter the village. Thirsty, they buy and drink three sodas. At least half of Luis' soda makes a sticky mess down his front, and onto the saddle and horse. This time, Chuy doesn't even flinch. He knows it can be cleaned up, and he doesn't want to disrupt the mood.

A group of small children trail along after the trio as they enter the PROJIMO yard. The workers in the metal shop stop work to watch and yell out greetings. Other children playing in PROJIMO run over to the horse and riders. Manolo proudly helps Luis down off the horse and returns the joyous child to his chair. Luis is overwhelmed with excitement as tears of happiness run down his cheeks. Chuy wheels his horse around, waves goodbye, and rides away content and a little embarrassed by Luis' tears. It's a moment he will never forget.

Manolo, on the other hand, has already forgotten where they have been and why they returned the way they did. He does know that he feels happy and proud when Luis smiles at him.

Later that night, when Manolo lifts Luis out of his chair onto his sleeping mat, Luis manages to get his arms wrapped around Manolo's back. When the time comes to let go, neither one of them does so. For a moment, the two friends hold each other quietly. When they do release their embrace, their eyes meet. Something they can't explain has happened, and they know it is important.

Manolo's Transition at PROJIMO

PROJIMO began as a program run by physically disabled villagers for physically disabled children and youth. But after a time, disabled persons of every age and with every kind of disability began to arrive. So the PROJIMO team tried to expand their knowledge and abilities to help persons of all ages and disabilities to meet their needs. With the help of visiting special educators and counselors they have learned something about mental handicap and developmental delay. But the team feels they still have a great deal to learn.

When Manolo was brought to PROJIMO by his mother, Mari and Conchita took charge of the consultation. Manolo was 14 years old but full grown and heavy set. His mother led him into the room and told him to sit down. Manolo silently obeyed, but he looked unhappy and angry. He did not answer when Mari greeted him; he just stared at his feet. His mother told Mari that Manolo gave her nothing but problems. "Yes, he can speak a few words," she said. "But usually he doesn't say anything ... especially around strangers."

Mari turned toward Manolo "What things do you like to do, Manolo?" Mari asked him in her friendliest voice.

"Nothing!" replied his mother. "He does nothing."

"Manolo, do you like to play games?" asked Mari, putting her hand on his broad shoulder.

"No!" said his mother. "He doesn't like to do anything. When he was little, I tried sending him to school, but he learned nothing. After 3 weeks the teacher sent him home. She said the other children were afraid of him."

"Do you like to watch T.V.?" Mari asked Manolo.

"No!" said his mother. "He doesn't like to do anything ... except to eat."

"What foods do you like, Manolo?" asked Mari.

"He eats everything!" said his mother.

Mari turned to her. "Give him a chance to answer for himself," she suggested gently.

"He won't say anything." answered his mother. "He doesn't talk to strangers."

It seemed she was right. His mother now kept silent and Mari tried to interest Manolo in a variety of things and to get him to say something. He didn't respond. Mari was unsure what to do next. Then, suddenly, Jorge rolled into the room with a loud whoop. Jorge was 14 years old but small for his age. He had two flail legs from polio and used a wooden wheelchair. On seeing that a consultation was in process he at once turned to leave.

"Jorge!" Mari called after him. "Please come here."

JORGE paused in the doorway. "What did I do wrong now?" he asked, frowning defensively. Jorge was a great mischief maker and always getting into trouble. He had first come to PROJIMO for leg braces and a wheelchair (which he much preferred). Two years later he had come back because his aging grandmother with whom he lives in the city said she couldn't manage him. She would send him to school but often he would spend the day - and sometimes the nights - in the streets or saloons. At times the police would bring him home drunk. In PROJIMO he also made trouble. But he went to the village school and was learning income-generating skills. Despite his pranks, he was a lot of fun and got along well with other children. He was especially good at befriending children who had recently arrived at PROJIMO and felt lonely and homesick.

"I need your help," said Mari. Jorge grinned. "I've been trying to learn what Manolo here likes or wants to do," Mari explained. "But he's shy and won't answer. Can you take him outside and show him the playground and shops. Maybe something will catch his fancy."

Jorge boldly rolled up to Manolo and took his big hand. "Come with me, compadre," he said. "I'll show you around." Manolo, looking gloomy, slowly rose and followed Jorge out the door. Although they were the same age, they looked like David and Goliath.

Mari stayed behind talking with Manolo's mother, who explained that she was worried because Manolo was so big and so bad tempered.

"Sometimes I'm afraid of him," she said. "He's so strong he could really hurt someone. And he's too big for me to control."

After a quarter of an hour the door burst open and Manolo came dashing in, followed by Jorge. "Mama! Mama!" He shouted. "Look at this!" He held up a colorfully painted wooden jigsaw puzzle. "Jorge make this!" he exclaimed. "I want make this! Jorge teach me!"

Manolo turned to Mari. He seemed a totally different person than the one she had been trying to get to speak a few minutes before. "Can I stay and make?" he asked Mari loudly.

"I hope so," said Mari. "We'll see what we can arrange."

Later that day, Mari asked Jorge what he had done to get Jorge to speak. "You won't be angry if I tell you?" asked Jorge. Mari shook her head. "I asked him if he wanted a cigarette" said Jorge, grinning devilishly. "That hooked him!"

Manolo stayed at PROJIMO for almost 6 months. As it turned out, he never did learn to make jigsaw puzzles. Although Jorge and others tried to take him through the process step by step, it proved too difficult for him. But he did learn to do many things, to live with a group outside his own family, and to gain a bit of self-respect.

One of the first jobs done by Manolo won him strong appreciation by the team. The tar-paper roof of the wheelchair shop had begun to leak and needed replacing. The tar-paper is held onto the wood struts with small nails. To prevent the tar-paper from tearing loose in the wind, bottle caps from soda bottles are used to give the nail heads a broader base. For this, each bottle cap has to first have a hole punched in it with a nail and hammer. One day, Jose was in the shop with a sack-full of hundreds of bottle caps, starting to punch the holes. Manolo was fascinated. "What you do?" he asked. Jose explained the chore. "I help!" said Manolo. Jose taught Manolo how to center a bottle cap over an iron sheet with a small hole in it, hold the nail in the middle of the cap, and hit it with the hammer. He guided Manolo through the first dozen or so caps. Then Manolo took over the job.

Manolo would punch holes for a while and then get distracted. But soon shouts would come from those on the roof asking for more bottle caps. With this feedback and encouragement for his work, Manolo persevered. When the new roof was completed, everyone celebrated. Manolo was praised along with the rest for getting the job done so quickly and well.

Manolo began looking for other things he could do to help. Because he is able-bodied and strong, and most of the PROJIMO staff are physically disabled, they would often call on him to help lift Quique (who was quadriplegic) out of bed and onto his wheeled cot. He also helped others who cannot move themselves. It was not long before Manolo became a real attendant, pushing the wheelchairs of those who needed help, and even assisting them with changing clothes and bathing.

For Manolo, this was a complete reversal of roles. From someone who was dependent and considered useless, he had suddenly become someone who had physical strength and ability others lacked. He was genuinely needed for this unusual ability!

When his mother came to visit she could not believe how her son had changed. When she took him home, she at first had a hard time readjusting to the new Manolo. For a while, both mother and son slipped back into the old pattern of accusation and apathy. But after a longer second visit by Manolo to PROJIMO, and some long discussions with his mother, things began to go better at home too. Manolo began to help with jobs around the house and even to help neighbors with simple tasks. But his real love was to be an attendant to physically disabled persons.

Manolo, by now, has probably forgotten Luis. And Luis may have forgotten Manolo. But Manolo gave Luis a degree of freedom, adventure, and joy of life he had not known before.

Jorge's fate. As for young Jorge, he went through some difficult times. In time, he was thrown out of PROJIMO for drunkenness, and ended up as a vagrant street youth. Fortunately, years later, Jorge was "rescued" by Leopoldo, another disabled youth who was expelled from PROJIMO (for shooting at a rival who was courting his girlfriend). Eventually Leopoldo became a leader in a self-help program of disabled youth in the city of Hermosillo, where he opened a wheelchair repair shop. On one of his travels, he happened upon Jorge in the northern border town of Tijuana. Jorge was sick from hunger and drugs and in despair. Leopoldo took Jorge back home with him to Hermosillo and arranged work for him in the workshop of the disability program.

The last we heard, Jorge was off drugs, healthy, self-reliant, and about to get married. Like many of us, he has had his ups and downs.

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA