Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

Part Six

CHILD-TO-CHILD:

INCLUDING DISABLED CHILDREN

CHAPTER 50

Mentally Handicapped Girls

Assist Multiply-Disabled Children:

Outcome of a CBR Training Course in Brazil

Helping Rehabilitation Professionals Listen to and Work as Partners with Disabled Persons

Brazil is a vast country of diverse cultures and striking contrasts. A small percentage of people are enormously wealthy. Millions live in poverty. Big cities have a few modern, highly sophisticated rehabilitation centers. But most disabled persons - especially those living in shanty towns and rural areas - receive little or no assistance beyond what their families can provide. Big barriers, both physical and social, lie in the way of full community integration.

An effort to improve this situation is being made by CORDE, a branch of the Ministry of Justice concerned with the integration and needs of disabled persons. CORDE is now committed to introducing Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) throughout Brazil.

In November, 1996, CORDE invited me (David Werner) to the coastal city of Recife to facilitate a one week course for future "multipliers" of CBR. According to an early plan, most course participants were to be rehabilitation professionals from government institutions. However, experience in many countries has shown that many of the most successful CBR programs are started from below by those who are most concerned: by groups of disabled persons and families of disabled children.

Therefore, to facilitate a partnership approach - and to open the way for disabled persons to play a leading role in planning and implementing CBR programs - it was decided that the course include:

- a substantial number of disabled participants (or family members), some of whom should be disabled organization leaders and activists;

- home visits and discussions with willing, local disabled persons/families living in difficult circumstances, to get their views on needs, obstacles, wishes, and ideas for priorities;

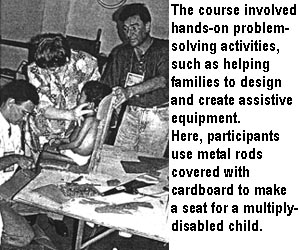

- hands-on, problem-solving activities with disabled children and their families, including making assistive devices with low-cost materials, designed for and with the individual child.

We felt that if the course could help rehabilitation professionals work together with communities, listen to disabled persons, and relate to them as partners and equals in the problem-solving process, much might be gained. The goal should be to encourage rehabilitation workers to EMPOWER, not merely to prescribe.

The CORDE staff did a good job of recruiting. Nearly one quarter of the course participants were either disabled themselves or were parents of disabled children. These disabled participants - who included leaders of disabled persons' associations, community service programs, and Brazil's budding Independent Living Movement - provided a key dynamic. They led discussions about needs and possibilities based on their own experiences.

COURSE PREPARATIONS. In preparation for the course, we facilitators visited a government-run hostel for abandoned, severely disabled children. Sixty children were cared for by an average of only 5 or 6 caretakers at any one time. Several of the most handicapped children appeared to be starving. Their wasted condition (marasmus) was apparently due, not to scarcity of food, but to a shortage of staff. Those children who had poor head-control and trouble swallowing could take only liquid foods in small sips. Getting enough food into them called for a lot of time and patience. With so many children to feed, clean, and care for, the few care-providers did not have time to adequately feed and mother those who needed extra help. As a result, these children were becoming more and more disabled. Apart from insufficient food, they got less hugging and stimulation than needed for their minds and bodies to grow.

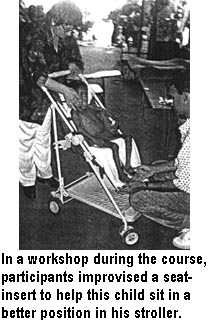

On arriving at this hostel, we saw a dozen disabled children lined up on the porch, sitting in wheeled strollers. All the strollers were exactly the same - regardless of the size, spastic patterns, or individual needs of the children. Their canvas seats were held by metal-tube frames. The children sat passively in half-reclining positions, like sacks of potatoes.

The strollers neither provided good positioning nor stimulated head and body control. For many of the children, the awkward positioning was leading to increasing spasticity and deformity. A few of the less severely disabled children were able to take a few steps with assistance, but they had no walkers. The one walker we saw was broken.

Given these children's extensive unmet needs, it occurred to me that - with some guidance and the use of books (such as Disabled Village Children) - the participants in the training course might be able to make simple, individually-adapted seats, assistive devices, and stimulating play-things for some of the children. With the help of the staff, we chose 6 children whom they agreed to take to a workshop to be conducted during the course.

CHILD-TO-CHILD. One day of the course was spent on Child-to-Child activities. Participants watched a slide-show from Mexico to spark their imaginations. Then they practiced Child-to-Child activities among themselves - including simulation games, role-plays, and discussions to sensitize school-age children to the needs and potentials of children who are different.

That afternoon, participants went to a public school. Small groups visited different classrooms. After ice-breaking games, they facilitated activities with the children. At first, the children were shy. But when they discovered that the adults actually listened to them and took interest in their ideas, the kids warmed up. They expressed their doubts and fears concerning disability. They acted out role-plays, and asked perceptive questions.

At the end, participants asked the children if they had liked the activities, and what they had learned. What they liked most, they said, was the chance to talk openly with the disabled members of our group, some of whom were blind or paralyzed. One of our group, Geronimo - who has flipper-like arms and marked deformities - quickly won the children's respect with his friendliness, candor, and self-assurance. One of their lingering doubts was put to rest when Geronimo introduced his vivacious young wife and said they were expecting a baby. The students agreed that the activities and discussions helped them realize that disabled people are ordinary people like themselves, with the same needs, emotions, and dreams. It is what we have in common that matters most.

THE APPROPRIATE TECHNOLOGY WORKSHOP. Two days of the course were spent in a small wheelchair-making shop run by disabled youth in a poor neighborhood. We facilitators had visited the shop beforehand to talk with the workers and to ask them for their help. We had told them that we hoped to bring disabled children from the government hostel (described earlier) so that the course participants could evaluate their needs, and try to make them simple assistive devices. The disabled shop-workers were eager to assist.

I had feared that a workshop with 60 participants would be total chaos. The situation might be overwhelming for the disabled children, especially those who were in delicate health. But my fears were soon calmed. On arrival, the participants formed 6 groups, each with a bewildered child. Among the participants were educators, psychologists, physical and occupational therapists, technicians, disabled persons, and - most important - mothers of disabled children. The mothers, especially, tried to gain the children's confidence, talking gently to them, then tenderly beginning to touch them and take them into their arms. The children, starved for human contact, began to smile and respond. Three participants with experience in evaluating children's needs and in designing assistive equipment, circulated from group to group offering assistance. At first, some participants were afraid to rely on their own observations, or to innovate. But the children's needs were so enormous that the groups started to improvise. The disabled shop-workers - used to building wheelchairs and walkers - began enthusiastically working on innovative designs. They assisted the different groups when their skills were needed.

The results were impressive. Using cardboard, sticks, cloth, and bits of tubing, the groups created a variety of useful assistive devices. They made special seats, wheelchair inserts, supports for improving body position and head control, a splint for better hand function, tray tables, and colorful toys to hang above a child to develop hand-eye coordination. The children seemed to like both the attention and equipment. The staff from the hostel were thrilled with the creativity. They said they would make equipment for other children, and were delighted to receive a copy of Disabled Village Children (in Portuguese) to provide ideas and guidelines.

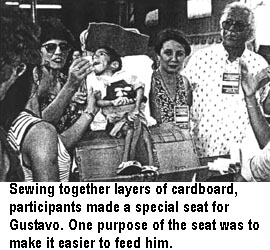

A survival seat for GUSTAVO. One of the children whose needs were most critical was Gustavo. Completely paralyzed by brain damage, the boy had been abandoned by his parents and ended up at the government hostel. Skin and bones, at age 14 he looked about 6 years old. Feeding him was hard, because his body and head were floppy and he had little mouth control. Although he could not to move or speak, his mental ability seemed intact. He could communicate only with his eyes. But he appeared to understand most questions. He would close his eyes to say no, and leave them open to say yes. At times, he almost smiled. Gustavo seemed to like both his new seat and all the attention. But sometimes when participants asked him questions, tears would roll down his checks - as if he were frustrated at not being able to communicate more effectively.

The participants realized that, although they were perhaps able to help Gustavo in a small way - such as a seat that would make feeding him easier - a lot remained undone. Gustavo needed a real home, a loving family, public assistance, and community support. "I never knew there were children like Gustavo in Brazil," said one rehabilitation center coordinator, tears in her eyes. "So starved! So neglected! And in our own institutions! How many more like him are there in Brazil?"

JOAO, the shop worker.

Joao, a young metal worker in the wheelchair shop, had one of his legs paralyzed by polio. He wanted to know if anything could be done so he could walk without having to push his thigh with his hand. A group of course participants tried to help Joao solve his problem. The group was encouraged to work with Joao as an equal in the problem-solving process, and not simply to design and make an assistive device for him. "Work with him as a partner, not a patient!"

Examining Joao's leg, the group found that he had a knee contracture of about 25 degrees which, if possible, needed to be corrected before Joao tried to walk with a brace. They did a test to find out whether the contracture was primarily in the muscles or in the knee itself (see page 127). If the contracture is in the muscles, it can often be corrected with exercise, casting, or bracing, to slowly stretch the tight muscles. If the contracture is in the joint capsule, surgery may be necessary.

To explain all this to Joao, the group used a life-sized plywood skeleton made in Mexico (see Chapter 20), which I had taken with me to Brazil. Joao enjoyed the demonstration with the skeleton, and said it helped him to understand the functions of his knee.

The group decided that the first step toward improving Joao's walking was to make a night brace to gradually correct his knee contracture. Among the course participants was an orthotist (professional brace maker) who helped Joao's group design a simple leg brace which they could make from two long, flat metal bars joined by curved sections of metal tube (materials that were available in the wheelchair shop).

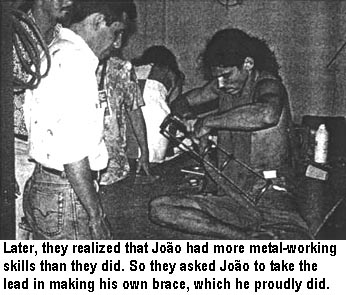

Joao was the only person in his group with the metal-working skills needed for making the brace. But when the group of professionals started working, the predictable thing happened. Joao was left sitting on the examining table, while the others began to cut, measure, and attempt to bend the pieces for the brace. Joao watched passively without comment. Then suddenly, one of the disabled participants woke up and said, "Hey! Joao is more skilled at metal-work than we are. And he knows more about his own leg. Rather than our making the brace for him, he should be making it himself, with our help. That way, if he has to adjust or re-make it after we are gone, he'll know how." Everyone agreed. With a grin, Joao climbed off the table and took charge.

Joao did an excellent job of making his brace. Everyone learned a great deal. But the most important lesson they learned was to work with a disabled person as a partner and not a patient. This is the key to enabling community rehabilitation.

CHILD-TO-CHILD: A MENTALLY HANDICAPPED GIRL LEARNS TO CARE FOR MULTIPLY-DISABLED CHILDREN

The course participants were deeply concerned about the inadequate care that disabled children at the hostel were receiving. They realized that the care-providers at the hostel were overworked. "The hostel desperately needs more staff, more help! Children are starving because they don't have enough attendants to feed them! In the current economic climate, the government cuts back on budgets for public services, even as the need grows. What can be done?"

IDEA! Then an idea came. Next-door to this hostel (part of the same institution) was a "home" for 50 abandoned mentally-handicapped girls. The girls were taught daily living skills, and many attended normal school (a big step forward). Some were also taught work skills. But as the girls got older, many had no place to go. So they stayed in the home with little direction or purpose in their lives.

A possible solution to the needs of both hostels was evident. One hostel needed more staff to help hold, hug, feed, and mother the multiply-disabled children. The other hostel had mentally slow girls with motherly instincts, who needed worthwhile activities.

Then why not invite the older, more capable mentally-handicapped girls to help feed and care for the severely disabled children?

Following up on this suggestion, on the second day of the CBR workshop, caretakers from the government hostel brought one of the older, more capable mentally-handicapped girls along with the 5 multiply-disabled children. The girl, MARIA, was eager to help. One of the course participants, herself a mother of a disabled child, showed Maria how to hold and handle EMA, a small girl with cerebral palsy who had almost no body control: Maria soon learned how to position and feed Ema in her new special seat (made by course participants). Another participant, a therapist, showed Maria how to help the child develop head control - by holding her upright and gently supporting the back of her head with her hands (see page 37).

Follow up. Everyone agreed that a big achievement of the course was the realization that a mentally slow girl like Maria could provide a vital service by caring for disabled children. Two course participants from Recife, a therapist and a priest, offered to visit the hostel regularly to help train Maria and other girls, and to assure that this Child-to-Child initiative is sustained.

Old Plastic Buckets Have Many Uses

Davidcillo is the son of Magui, who has severe arthritis and runs the cooperative village store in the village of Ajoya. PROJIMO often provided child care for the baby while his mother tended the store. (See the photos of Martin holding and bathing Davidcillo on pages 22 and 236.) The baby was named after the author.

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA