INTRODUCTION

A. Purpose

In the developing countries of Asia and the Pacific, poor people with disabilities are frequently trapped in a vicious cycle of exclusion from society and mainstream development programmes. Without appropriate assistive devices, they often lack the means to participate in education and training programmes for independent living and contribution to the development process. The resulting lack of skills is a barrier to employment. Without income from work, people with disabilities remain poor, and thus unable to purchase assistive devices. Given these conditions, for many people with disabilities, assistive devices are a basic need a need as important as adequate shelter.

At its forty-eighth session in 1992, the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) declared the period 1993-2002 as the Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabled Persons, with the goal of full participation and equality of people with disabilities. In the following year, at its forty-ninth session, the Commission adopted the Agenda for Action for the Decade. Assistive devices constitute an important area of that Agenda.

The availability of appropriate assistive devices that are affordable by the majority of people who need them, or by government agencies and non-government organizations (NGOs) working on their behalf, is one of the changes that people with disabilities in Asian and Pacific developing countries require in order to live and work independently. Full equality of opportunity requires substantial changes in social attitudes and physical accessibility. If changes in both of these areas are to make a significant contribution, it is imperative that people with disabilities be enabled to use assistive devices. With that, they may themselves help to bring about the required changes.

Following the declaration of the Decade, Governments in the ESCAP region are increasingly interested in introducing and strengthening legislation and policies to protect the rights of people with disabilities. The availability of low-cost, appropriate assistive devices is a necessary part of protecting these rights.

There is a wide gap between the availability of appropriate assistive devices and the need for such devices. Some of the available devices are designed, produced or distributed in such a way that their worth for users is limited. In other cases, the production of new and useful devices is confined to certain geographical areas, while needs elsewhere within a country or in other parts of the region remain unmet.

This situation is caused, at least partially, by the inadequate availability of information. So far, personnel working with assistive devices do not have a strong regional network to exchange information. They are often unaware of innovative solutions found elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region.

The aim of this publication is to help remedy this situation by providing information on the indigenous production and distribution of assistive devices in Asian and Pacific developing countries. Together with the Technical Workshop on the Indigenous Production and Distribution of Assistive Devices held in Madras(1), India, in September 1995, the issuance of this publication is part of an ESCAP project to strengthen contact among personnel concerned with assistive devices and to raise the awareness of Governments in the region about the potential for meeting the demand for low-cost devices appropriate to users and their physical, cultural and social environments.

This publication focuses primarily on devices for people with lower-body locomotor disabilities (i.e., amputated or non-functional legs). Overall, this group currently has the most pressing unmet needs for appropriate devices. Devices for this group typically require the greatest amount of customization. Since the production of their devices is less easily standardized, it is often less profitable. The group's numbers are also large and increasing as a result of disabilities associated with land mines, armed conflict, as well as accidents related to sports, traffic and occupational hazards.

The publication does not deal at length with assistive devices for people with mental disorder or intellectual disabilities. Their needs, although important, are beyond the scope of this publication. People who work with assistive devices in Asian and Pacific developing countries will find that this publication informs them about diverse approaches to production, and about producers and organizations they can contact. People whose work relates to other aspects of disability and rehabilitation issues should also find this publication useful, since assistive devices are a key aspect of all efforts to empower people with disabilities.

In addition, the publication should prove valuable for those who are involved with development or policy, in the Asia-Pacific region, in areas other than disability. It aims to demonstrate not only that the need for assistive devices in the region is urgent, but also that it can be met easily and at low cost through collaboration in a variety of fields.

Those researchers in applied science, mechanical and chemical engineers, and manufacturers who are not working directly with assistive devices may already be producing raw materials or parts that can be used in assistive devices. The examples contained in this publication demonstrate a potential and emerging market for these products.

Readers from or working in least-developed countries should not assume that their lack of resources is an impassable barrier in providing assistive devices for people with disabilities. Cambodia, classified as a least-developed country, has a highly developed system for producing and distributing assistive devices involving cooperation between NGOs and the Government.

B. What are assistive devices?

Assistive devices (also known as technical aids, assistive equipment or assistive technology) are items that can directly enable people with disabilities to participate in the activities of daily life. People with disabilities may use assistive devices on their own or with the support of other people.

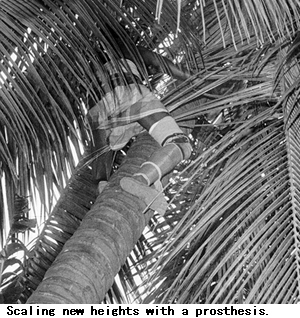

There are many types of assistive devices, all of which have a major role in improving people's lives. Communication boards help children with speech impairments to express themselves. Prosthetic feet allow amputees to walk. Braille writing slates enable people with visual disabilities to record information by themselves. Computers help people with visual impairments to communicate in text format. A loop-induction system makes it possible for someone with a hearing impairment to enjoy a musical performance.

Assistive devices reduce barriers between people with disabilities and their environments. In work, education or leisure, they bring about freedom of movement and greater ease of access. In some cases, assistive devices make it quicker and easier for people with disabilities to undertake activities that would otherwise be difficult; in others, they enable people to perform activities that would otherwise have been impossible. Assistive devices have a central role in social policy. They empower people with disabilities to live with dignity as equal members of society and give them a new freedom and independence. That independence can reduce the cost of disabilities to individuals, to families and to society. Furthermore, the resulting enhancement in the quality of life of people with disabilities leads to the generation of new aspirations, new capacity to promote improvements in devices, and thus new innovations, in a continuous positive-feedback loop of innovation.

C. Evaluating assistive devices

The success of an assistive device is measured by whether its users actually use the device, do so in an effective and liberating way that gives them access to their environments, and are satisfied with the device in the long term. To achieve this goal, every assistive device in Asian and Pacific developing countries should have four primary qualities. Devices should be:

- Designed in consultation with users and their families in a way well suited to the users' diverse social and physical environments;

- Inexpensive to produce, purchase and maintain;

- Easy to use;

- Effective.

Devices originally designed for use in developed countries and imported directly from them are usually effective; i.e., they are capable of performing the functions for which they are intended. However, they often lack the other three qualities. For example, a high-technology hearing aid may have the capability to provide beautifully clear sound to its user, but if its user must make a three-hour journey just to find new batteries, it will likely not be used once the batteries are dead. Under such circumstances, the capabilities of a device will be wasted. The best device that money can buy is not necessarily the best for users.

To ensure that a device has all four of these qualities requires a clear understanding of user needs. It also requires the direct involvement of potential users at each stage of design and development.

A list of features that give a device the four essential qualities (other than effectiveness) follows.

1. Devices designed to suit users and their environments

- Compatible with the users' aspirations, emotional needs, and ways of life;

- Compatible with the users' culture and local customs;

- Unobtrusive or attractive in appearance by local standards;

- Physically comfortable from users' perspectives;

- Sturdy enough that the users feel safe;

- Useful in a variety of situations;

- Durable, dependable and reliable, especially in rural areas, remote areas and rugged conditions;

- Compatible with the ground surface and other conditions of a user's physical environment.

2. Inexpensive devices

- Low in purchase price, so that a larger number of users than is presently the case can buy them, and Governments and/or NGOs can provide them free of charge or at subsidized rates;

- Easy (and affordable) to assemble or produce, for anyone with an interest in empowering people with disabilities, an aptitude for technical work, and appropriate short-term training;

- Easy and affordable to maintain, so that keeping the devices in working order requires minimal regular consumption of expensive or scarce resources;

- Amenable to repair with the use of locally available materials and technical skills, in or near the users' own communities.

3. Easy-to-use devices

- Easily understandable by users with limited exposure to technology;

- Easily moved from one place to another;

- Easy to operate without prolonged training or complex skills.

D. What is a disability?

The terms "disability", "handicap" and "impairment" are used in many different ways to cover a vast range of conditions. The most commonly cited definitions are those adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1980.In the context of health experience, WHO defined impairment, disability and handicap in the following ways(2):

- An impairment is any loss or abnormality of psychological, physiological or anatomical structure or function;

- A disability is any restriction or lack (resulting from an impairment) of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being;

- A handicap is a disadvantage for a given individual, resulting from an impairment or a disability, that limits or prevents the fulfilment of a role that is normal (depending on age, sex, and social and cultural factors) for that individual.

People who wear glasses have a disability in that their sight is less than perfect. The availability of the glasses they need to see clearly, however, means that, for them, the disability of poor eyesight is not a handicap. It is the handicap, rather than the disability, which creates difficulty and must be dealt with. Assistive devices reduce, if not eliminate, the handicap.

E. People with disabilities in Asian and Pacific developing countries

1. Poverty and other causes of disabilities

The majority of people with disabilities are likely to be poor. The following are among common poverty-related causes of disability (subdivided by type of disability):

- For locomotor disabilities: Leprosy; poliomyelitis (polio). In India, polio is the single largest contributor to the prevalence of locomotor disability; in heavily mined Afghanistan, a Handicap International survey found that polio caused more disabilities than land mines. Furthermore, poverty reduces options and compells many to risk disability resulting from the need to work in mined areas.

- For hearing disabilities: Rubella during pregnancy; iodine deficiency and diseases such as meningitis, hepatitis, typhoid or measles in early childhood; ear infections at any time in life.

- For visual disabilities: Vitamin A deficiency (in children); leprosy; and cataract (without access to surgery and rehabilitation).

- For multiple disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy): Maternal stress, unsafe birth practices and perinatal trauma associated with conditions of poverty.

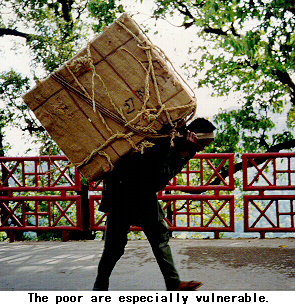

Furthermore, the ensuing disabilities have more serious consequences for the poor, who have limited access to rehabilitation services and assistive devices. Even when poor families can theoretically afford assistive devices, they may still assign a lower priority to using their scarce resources on the purchase of devices than to food and shelter. The poor are also more likely to live in an environment whose handicapping features are overwhelming.

The aforementioned causes are all preventable with proper use of resources. Developed countries have all but eliminated them, and many developing countries of the ESCAP region are making progress toward their elimination. In Pakistan, for example, there is a campaign to immunize all Pakistani children against polio within the next five years.

Furthermore, absolute poverty can be a more severe limitation on life activities than disability per se. Obtaining a brailler will be of low priority for a blind person who faces death from starvation. All who are concerned with disability issues must bear in mind that assistive devices are only one element of a national disability strategy. Poverty alleviation and provision of adequate health services are central.

Nevertheless, poverty alleviation itself requires the availability of appropriate assistive devices. To fight poverty, all the members of a family, including those with disabilities, must contribute to the family economy. Without the appropriate devices, family members with disabilities may be a burden. With appropriate devices, along with changes in access and social attitudes, they can contribute productively. For this reason, in the rehabilitation of poor people with disabilities, it is especially critical that the devices provided facilitate their participation in activities of economic value to their families.

Although poverty is a major cause of disability, many other causes exist, and anyone can acquire a disability at any point in life. People in the middle and upper classes of the Asia-Pacific region are not immune.

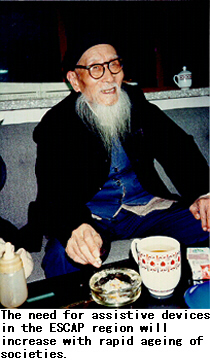

Among older people, hearing and vision can deteriorate to the point where they become impossible without assistive devices. A stroke can cause paraplegia. A fall can cause limb damage that does not heal.

Among young people, accidents involving motorized vehicles or outdoor activities can cause spinal cord injury leading to paralysis. Regular and prolonged exposure to noise in mass entertainment venues may lead to hearing impairment.

Newborn babies can have genetic disabilities, even if their parents do not. In addition, although perinatal birth trauma is most common among the poor, it can lead to disabilities even in babies born to wealthy families.

Two other causes of disabilities that are uncommon in developed countries exist in developing countries of the ESCAP region. One is the existence of uncleared anti-personnel landmines in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Islamic Republic of Iran, Myanmar and Viet Nam, and unexploded ordnance (UXO) in the Lao People's Democratic Republic, which regularly destroys life and limb. Over 10 million mines remain uncleared in Afghanistan. In Cambodia, one in every 236 people is an amputee because of mines. In Myanmar, over 1500 people every year are fitted with artificial limbs as a result of landmine explosions. Many mine victims never receive medical attention at all(3).

The second cause is poor adherence to safety measures in mechanized farming. In manual farming, operators can stop machines quickly and easily when a problem arises. In mechanized farming, however, control switches may not be within easy reach of the operator or safety guards may not be in position, leading to serious injuries which result in disabilities.

In both these cases, victims will clearly need assistive devices. Demining programmes, support for campaigns to ban landmines, and better safety standards for farm equipment and training can, however, reduce this need in the future.

Violence at home and in public places may also result in disability. When violence involves the use of guns and other lethal weapons, survivors are often permanently disabled by spinal cord injuries.

2. Levels of need for assistive devices

There are no firm data on the number of people with disabilities in developing countries of the ESCAP region. Most developing countries have not conducted any comprehensive surveys on the subject. This poses problems for both planning and evaluating programmes to provide assistive devices. Without such surveys, people will neither know what assistive devices are needed nor know how much of that need is being met.

In countries that have disability statistics, the number of people with disabilities, expressed as a percentage of the country's total population, varies from 1.85 per cent in Thailand to 10 per cent in Pakistan(4). It must, however, be stressed that such figures represent differences in methodology or definitions of "disability" as much as differences in the population itself. The figure of 1.85 per cent for Thailand, for example, comes from interview and questionnaire surveys conducted in 1991. A 1991-1992 Thai study, however, used physical examination of the population as its method and concluded instead that 6.3 per cent of the population more than three times as many had disabilities. Furthermore, unlike the survey study, the physical-examination study did not examine people for the presence of intellectual disabilities. It is estimated that, if the survey had included them, the figure found would likely have been around 8.1 per cent instead(5). It is likely that the latter method is more accurate, but it requires a more comprehensive definition of disability and concomitant allocation of resources.

These figures demonstrate the difficulty of obtaining a realistic estimate of the number of people with disabilities, especially in rural areas. At the macro level, numbers are important for planning a coordinated system to supply assistive devices. An effective assistive-device service, however, can only be provided through a network with delivery channels at the micro level, channels which can capture an understanding of the needs of every disabled person. This is more easily achieved by local authorities and NGOs than national, provincial or state Governments.

About 90 per cent of China's people with disabilities need at least one assistive device(6). A survey in Viet Nam asking people with locomotor disabilities about their needs found that 67 per cent required an assistive device(7). In Thailand, 66,712 people needed at least one device in 1995: about 83 per cent of the total registered population of people with disabilities, numbering around 80,000. The government registration roster does not, however, include all Thai people with disabilities. Thailand's experience further demonstrates that much of the demand for assistive devices is not currently being met. The Thai Central Government Budget for 1995 provided funds for only about 20,000 people with disabilities(8).

As a country undergoes rapid economic and social change, the patterns of disabilities in that country will also change rapidly. In Thailand, for example, the number of people with disabilities resulting from polio has decreased in recent years, but the number with disabilities resulting from traffic accidents has increased(9).

The unmet need for assistive devices is usually greatest in rural and remote areas. Sometimes, this is a result of a greater overall need; more often, it is because production and distribution are concentrated in capitals and other major urban centres. In Indonesia, for example, the vast majority of device producers are on Java island and few high-quality devices are available elsewhere. In Fiji, the only sources of devices are in Suva.

It is wrong to assume that the need for specific devices is distributed evenly among or within geographical regions. Needs differ in relation to variations in the incidence of disabilities, local conditions and individual differences. The need for orthoses, for example, is greatest in places where poliomyelitis and cerebral palsy are major causes of locomotor disabilities. Furthermore, even small geographical areas may differ greatly within themselves in the needs they face. Workers for Handicap International observed a case in southern Thailand where ten blind people lived in one village while a neighbouring village had no blind inhabitants at all.

3. Women and girls with disabilities

Most women and girls with disabilities in every community, whether urban or rural, experience triple discrimination from being female, disabled and poor. As women's needs generally receive lower priority than men's, so women with disabilities receive a lower priority for obtaining assistive devices. According to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), women and children together receive less than 20 per cent of rehabilitation services, including the provision of prostheses and orthoses(10).

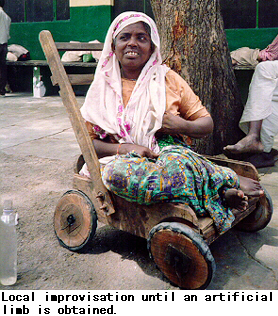

Furthermore, with few exceptions, little effort has been made to obtain the views of women and girls with disabilities concerning assistive devices or to incorporate their views in the design and production of the devices; as a result, the devices often do not suit them. For example, in many parts of the region, food is prepared at ground level. In order to cook, many women with post-polio paralysis drag themselves on the ground or use a simple wooden support block, rather than use a wheelchair. Ground mobility devices (see the Technical Specifications Supplement) are a useful way to deal with this problem. For another example, above-knee prostheses are difficult to adjust for pregnant women, and little research has been done into designs that are more suitable for pregnant women.

4. Older people and children with disabilities

Older people and children with disabilities require special attention. Older people are likely to acquire disabilities as a result of old age. Many resist being labelled as "disabled", and are therefore reluctant to use assistive devices, even though the devices could significantly improve their lives. They are also more susceptible than others to multiple disabilities. The need for different types of assistive devices, or for devices specially designed for people with multiple disabilities, will therefore be higher among them.

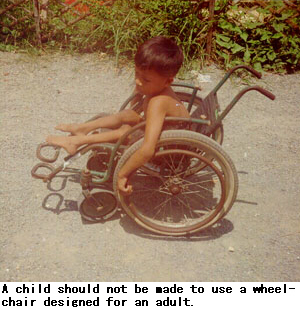

Children require devices whose size and ease of manipulation suit them. A child should not be made to use a wheelchair designed for an adult, but this remains a common occurrence. Furthermore, growing children require regular attention to ensure that they are not constrained by devices that they have outgrown. For example, a three-year-old child will outgrow an orthosis in a few months' time. Unless the old orthosis is updated or replaced, the child's development will be hampered.

Devices that do not fit a child's needs can do more harm than good. For example, a child who tends to walk with bent knees may topple over backwards when wearing an orthosis whose ankles are fixed at 90 degrees. Bracing designed to correct the effects of spasticity in children with cerebral palsy may occasionally trigger even more spasticity. Well-designed orthoses can be of great benefit to children with cerebral palsy and other disabilities, but it is crucial that the devices be approached in an experimental, open-ended, trial-and-error way where each child's feelings, responses and concerns are made central to the problem-solving process.

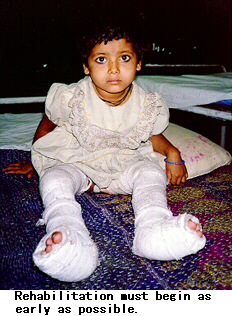

Although there are exceptions, children below the age of three years are generally the group most vulnerable to polio. Paralysis caused by polio at this early age often hinders children from walking properly. For the development of their full potential (physical, mental and social), rehabilitation must begin as early as possible. This is even more so in the case of children with disabilities resulting from birth trauma, as they may have multiple disabilities.

1. Officially renamed Chennai in 1996.

2. United Nations, Department of International Economic and Social Affairs. World Programme of Action concerning Disabled persons. New York, 1983, p. 3.

3. "Uncleared Land Mines: the Scope of the Problem in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the Americas, and Europe", UNIDIR Newsletter, No. 28/29, Dec. 1994/May 1995, p. 47.

4. Pakistan and Thailand country papers, in Part II: Madras Workshop Proceedings.

5. Information provided in July 1997 by the Department of Public Welfare, Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare, Royal Thai Government.

6. China country paper, in Part II: Madras Workshop Proceedings.

7. Ho Nhu Hai, "Motor Disabled People in Rural Areas of Vietnam", paper presented to the Round Table Meeting on the Integration of Disabled People in Agricultural and Agro-Industry Systems, held by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 13-15 May 1997, Bangkok.

8. Thailand country paper, in Part II: Madras Workshop Proceedings.

9. Health Research Institute/National Health Foundation, Ministry of Public Health, Royal Thai Government, 1992.

10. UNICEF, Relief and Rehabilitation of Traumatized Children in War Situations. Paper submitted for the World Summit on Children, 1990.

Box

Box 1: Who Can Use This Publication?

This publication is directed at the following groups in the developing countries of the Asia-Pacific region:

(a) Government policy makers and programme personnel responsible for:

- (i) Disability issues;

- (ii) Health;

- (iii) Social welfare and community development;

- (iv) Science and technology, especially research and development;

- (v) University research;

- (vi) Education and training;

- (vii) Employment promotion;

- (viii) Rural development, especially technology and skill development;

- (ix) Technical cooperation among developing countries (TCDC).

(b) University and private research personnel conducting research on:

- (i) Disability issues;

- (ii) Rural development;

- (iii) Technology and applied science.

(c) Management and personnel in industries producing:

- (i) Thermoplastics;

- (ii) Semiconductors;

- (iii) Microcellular rubber;

- (iv) Microfibres;

- (v) Bicycles;

- (vi) Motorcycles.

(d) Personnel of philanthropic organizations supporting:

- (i) Equal opportunities for people with disabilities;

- (ii) Rural development;

- (iii) Appropriate technology;

- (iv) Self-help initiatives of marginalized groups.

(e) NGO personnel and community members working on issues concerning:

- (i) Disability and assistance to people with disabilities (from programme to individual levels);

- (ii) Rural development;

- (iii) Community action;

- (iv) Technology;

- (v) Empowerment of marginalized groups.

(f) People with disabilities involved in:

- (i) Advocacy for protection of their rights or equalization of opportunity;

- (ii) Empowerment of their peers;

- (iii) Rehabilitation service delivery.

Box 2: Examples of Assistive Devices

(a) For people with locomotor disabilities:

- (i) Orthoses;

- (ii) Prosthetic limbs;

- (iii) Wheelchairs of various types;

- (iv) Tricycles, manual and motorized;

- (v) Crutches;

- (vi) Foot-drop spring shoes and other devices for people cured of leprosy.

(b) For people with hearing impairments:

- (i) Hearing aids of different types (body-level, behind the ear, and in the ear canal);

- (ii) Group hearing aids, such as loop-induction systems;

- (iii) Communication boards;

- (iv) Telephone amplifiers;

- (v) Vibrating alarm clocks.

(c) For people with visual impairments:

- (i) Braille slates;

- (ii) Braille typewriters;

- (iii) Computerized braille embossers;

- (iv) Stylus;

- (v) Braille paper;

- (vi) White canes;

- (vii) Braille geometry sets;

- (viii) Pinhole masks;

- (ix) Optical magnifiers for people with low vision.

(d) For people with multiple disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy):

- (i) Communication boards;

- (ii) Rollators (walking devices with rollers);

- (iii) Stimulation devices for toilet training;

- (iv) Bolsters and balancing balls;

- (v) Learning devices;

- (vi) Adapted cutlery and crockery, such as spoons with special grips;

- (vii) Positioning devices, such as special seating.

Box 3: Twelve Principles of Assistive-Device Production and Distribution

Participants in the Technical Workshop on the Indigenous Production and Distribution of Assistive Devices (held in Madras, India, 5-14 September 1995) agreed on 12 principles for the production and distribution of assistive devices. They are reproduced in their entirety in the Madras Workshop Proceedings, and are summarized here:

- People with disabilities must define their own needs and be involved as equals in designing and testing assistive devices in a problem-solving approach to decision-making that empowers persons with disabilities.

- The choice and design of assistive devices must suit the user's lifestyle, culture and environment.

- People with disabilities should, when possible, be given priority for work and training related to assistive devices.

- Devices must be made to fit users, not vice versa.

- Support should be directed at strengthening small-scale community workshops that allow users' needs to be met by custom-made devices.

- Local skills, materials and other resources should be used for production, repair and maintenance.

- The design and production of assistive devices should be explained to local communities with limited exposure to sophisticated technology in such a way that they can make and adopt the devices.

- Community-level innovation should be emphasized, and community collaboration with disabled persons and researchers encouraged.

- Assistive devices should be seen as a part of the process of enabling people with disabilities to achieve their full potential;

- Training and follow-up are essential for ensuring the continued appropriateness of assistive devices for users.

- Decentralized production, achieved partly through widespread dissemination of knowledge and skills, is one way to meet user needs in remote areas;

- Distribution of information on technologies and problem-solving skills supported by networking and exchange of products and training expertise, is as important as distribution of devices.

Box 4: Current Definitions: Impairment, Disability and Handicap*

Impairment: Any abnormality of psychological or physical functions or of appearance.

Disability: An interference with the performance of an activity by an individual in relation to the immediate environment

Handicap: A societal disadvantage for a given individual that limits or prevents the performance of a social role or participation.

In general, impairments result in disabilities, which result in handicaps of social integration. However, the relationship is not necessarily causal or unidirectional.

| Terms: | Impairment | Disability | Handicap |

| Levels: | Organ | Person | Society |

| Disablement: | Body structure/ function | Activities | Roles |

| Traumatic Injury: | Loss of an eye | Limited depth perception | Unable to obtain a driving licence |

| Example | Impairment | Disability | Handicap |

| Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder | Minimal brain damage, distractibility, problems in concentration, high activity level, writing difficulty | Attention deficit(learning disability), difficulties completing tasks and waiting for turn in groupactivities | Viewed/labelled by others as "a problem"and excluded from activities considered normal for peers of the same age and family background, living in the same community |

* Source: Excerpted from information provided by Dr. T. Bedirhan Ustun, Senior Scientist, World Health Organization Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Abuse, and Coordinator of the second revision of the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicap (ICIDH), WHO, 1980. The ICIDH is being updated and the second revision is scheduled for 1999. For further information, contact Dr. Ustun: 20 Avenue Appia, CH-1211, Geneva 27, Switzerland; Fax: +41 22 791 4885; Tel: +41 22 791 3609; Email: Ustun@who.ch Trends of Population Aged over 60 in Developing Countries of the ESCAP Region Million 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 Source: World Population Prospects, the 1996 Revision.

Go back to the Contents

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Production and distribution of assistive devices for people with disabilities: Part 1

- Chapter 1 -

Printed in Thailand

November 1997 1,000

United Nations Publication

Sales No. E.98.II.F.7

Copyright c United Nations 1997

ISBN: 92-1-119775-9

ST/ESCAP/1774