ASSISTIVE DEVICES AND

INCLUSION IN SOCIETY

The initiatives of the Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabled Persons aim to foster an environment which will provide equal opportunities for people with disabilities and enhance their options for full participation in society. Assistive devices built into the environments of people with disabilities help achieve this objective by enabling disabled people to participate in mainstream community life, including employment, education, family activities and recreation.

For example, a proper lighting system and strong colour contrast in the built environment will help people with low vision to perform tasks better. Such a lighting system would be additional to their use of magnifying devices. People in wheelchairs who have reachers (see Technical Specifications Supplement) or extended hooks will find it easier to take things from shelves at a height. Blind people must currently rely on sighted people to read their own bank statements. With the advent of small computerized braille embossers, it should be possible to issue braille bank statements to blind customers. However, for this to occur, banks must adopt a policy to this effect and bank employees must be persuaded to implement the policy as a matter of course.

A. Access

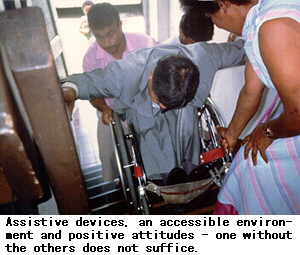

Having appropriate assistive devices per se is not enough to enable people with disabilities to participate in mainstream development programmes and community life. Assistive devices must be considered together with access to the built environment and a social milieu that welcomes the participation of persons with disabilities. An integrated solution is required to produce a significant enhancement in the participation of people with disabilities in society. Without accessible environments and positive attitudes, users of assistive devices continue to face similar difficulties to those they would face without assistive devices.

On the other hand, making environments both physically and socially accessible can be a futile effort if assistive devices are not available. Installing ramps to make a school accessible for wheelchair users will help little if students who require wheelchairs do not have them. Furthermore, no matter how accessible the environment and how useful their devices, people with disabilities will still be excluded from society without progress in the elimination of discriminatory practices.

The built environment is composed of buildings and other physical structures, the spaces around and between those structures (however far the distance between them may be), and the infrastructure which makes it possible for people to move to, from and within built areas.

A non-handicapping, or barrier-free, environment is one to which people with disabilities have access. Access to a space in the built environment means that people can get to, from and around the space and use it in a safe and convenient way. Conversely, a handicapping environment is one which is unsafe, inconvenient or impossible for people with disabilities to move around in. Handicapping environments are the prevailing situation in many Asian and Pacific developing countries.

Features which should be accessible to people with disabilities include entrances, exits, door handles, corridors, toilets, escape routes, refreshment facilities, elevators, staircases and parking. Ways to improve access include installing water coolers, telephones and counters at wheelchair height, to enable wheelchair users to use them without assistance. Braille markings in elevators enable blind people to operate them independently. Similarly, a change in the texture of the ground near an elevator enables blind people to clearly identify the elevator doorway(11).

Different buildings and spaces in Asian and Pacific developing countries must be made accessible in different ways. In South-East Asia and in the Pacific, for example, houses are often built on stilts. The height of these houses varies from three to five metres. Stairs or ladders are used for entry and exit. If stairs are the only entrance and exit, a person in a wheelchair cannot go in or out. A hoisting system using pulleys and cables is useful to transport people with lower-limb disabilities or cerebral palsy.

Thus appropriate assistive devices, together with an accessible built environment and positive attitudes, significantly enhance the inclusion of people with disabilities in society.

B. Education

Children with disabilities often require assistive devices to participate in education. Sometimes, lack of one assistive device is all that separates a child from participation and inclusion in a regular school. With the right device, a child may not have to attend a special school, segregated from peers without disabilities.

People with disabilities may not be able to realize their right to an education without assistive devices. People with upper-body locomotor disabilities require assistive devices to write, and children with lower-body locomotor disabilities require them in order to attend classes.

People with hearing disabilities require assistive devices to hear their teachers and participate in class. However, services for assessing hearing impairments, prescribing hearing aids and producing them for distribution to people with hearing impairments are limited.

People with low vision require assistive devices to read notes, books and blackboards, and very few have them. The International Council for Education of People with Visual Impairment (ICEVI) estimates that 90 per cent of the world's people with visual disabilities do not have access to an education(12). Blind people can receive the great benefits of braille-related assistive devices such as embossers and slates only if they have learned how to read braille. Currently, the majority of blind people in Asian and Pacific developing countries have not been enabled to do so.

An inexpensive way to distribute assistive devices in education is for a government ministry or department to maintain a stock of assistive devices to lend to students. When the students complete their studies or outgrow their devices, they may return these devices to the ministry or department. This approach is not suitable for the most user-specific devices, such as prosthetic limbs.

Teachers should have a basic working knowledge of different types of childhood disabilities and the corresponding types of assistive devices, in order to address the needs of children with disabilities in their classrooms. This would put teachers in a better position to discuss children's needs for devices, in school and home-based activities, with parents and health workers.

C. Employment

1. Agriculture and other rural employment

People with disabilities in rural areas should be employed in their own surroundings unless the reasons for doing otherwise are compelling. For example, a person who has been trained in technical skills may prefer to work in an industry rather than getting into traditional trades. Others may choose to migrate to urban centres to find more remunerative employment. If people themselves do not choose to leave their rural communities, however, they should not be forced to do so because of lack of options associated with their disabilities.

It is therefore crucial that rural environments be made accessible. Many employment options in rural areas are open to everyone, including people with disabilities. Such options are found, for example, in agriculture, horticulture, animal husbandry, handicrafts, carpentry, tailoring, blacksmithy and mechanical or electrical repair work.

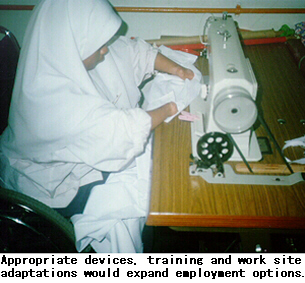

On-site modifications to workplaces are often, but not always, essential. This depends on the type of disability and type of work. The modifications may be as simple as lowering the height of a work surface or lengthening everyday gardening tools so that wheelchair users can use them. Whether or not modifications are essential, assistive devices must be suitability designed, modified and produced for the tasks involved. Lower-limb amputees working in rice fields, for example, must have prostheses designed in such a way that they can wear it to work in the fields.

Tractors and harvesters can be adapted for use by people with disabilities. This may require small modifications in the machines, such as adding one or more steps to the driver's seat for people wearing orthoses or prostheses. Modification of the height and position of the seat, or the replacement of foot controls with hand controls, may also be required.

2. Employment in the manufacturing and service sectors

Many service jobs available in Asian and Pacific developing countries, such as those of bookkeepers and clerks, do not necessarily call for special devices. Technical jobs may sometimes require on-site modifications to enable disabled people to work on machines or to improve their efficiency. Generally, the layout of assembly lines and machines does not take the needs of people with disabilities into consideration.

The built-in safety of many high-technology machines is an asset for disabled people, as they can safely and easily operate these machines. When replacing existing machines, industries and workshops in the region, especially public-sector ones, should install machines based on principles of universal design. They may highlight this aspect in tender notices and purchase queries for new machines.

In the Veterans International production workshop in Phnom Penh, wheelchair users are able to operate an injection moulding machine because the bed of the machine has been lowered to match the height of their wheelchairs. The Sheltered Workshop, a vocational training centre in Klang, Malaysia, has sewing machines whose height can be adjusted to suit the height of individual wheelchair users.

Adaptations to machines are extremely important for people with visual impairments. Some examples follow.

To enable blind people to perform precision measurement tasks, micrometers with braille attachments are available. At Bharat Earth Movers Ltd. in Bangalore, India, a blind person is engaged in a drilling job. He uses a jig to fix the job and then drills a hole at the right place. In another factory in India, a blind person operates a small machine with a checking mechanism. He can close and open the chuck for polishing watch dials. The machine is preset for the depth of finish and the blind person has to ensure proper fixing of the job in the chuck before performing the actual operation(14).

Assistive devices such as closed-circuit television with magnification facilities, reading machines, computers with large-print displays, speech synthesizers and braille embossers can enable blind people and people with low vision to manage offices.

To encourage open employment, Governments could provide such devices to any industry recruiting blind people. Several developed countries have this policy. Under such a policy, the Government concerned normally requires the return of such devices if the blind person in question leaves the position and his or her replacement is not blind.

In inspection and quality-control workshops in industry, blind people can be very effective when a "go" / "no go" decision is involved. In such cases, the analog output of a measurement gauge can be converted into an audio output to indicate whether a part has passed the quality requirement. Many such jobs are available in large industries. Work sites need to be studied carefully on a continuous basis in order to support more such adaptations.

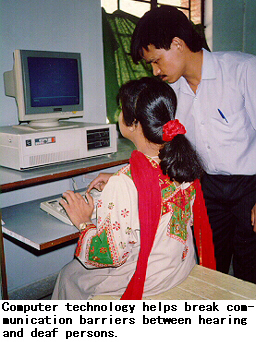

People with hearing impairments can use telephones which incorporate flashing lights to draw their attention to incoming calls. Similarly, all emergency signs may be coupled with flashing lights.

For various reasons, many people with disabilities who are employed do not use the applicable assistive devices. This makes their jobs tiring and reduces their efficiency. At the time of recruitment, the need of people with disabilities for assistive devices must be properly assessed. Subsequently, arrangements must be made to provide the devices that will enable them to perform their tasks to the best of their ability.

There are many examples of on-site modifications in industries, adaptations to existing devices and design and development of new devices. However, these experiences have not been properly documented for others to use in their own situations. A document highlighting such experiences would be helpful.

D. Recreation

People with hearing impairments find it difficult to enjoy mass audio entertainment. In an enclosed entertainment venue, it is possible to enclose a small area with a loop-induction system so that people with hearing impairments within it can hear voices and sounds without ambient noise. A loop-induction system comprises of a microphone, an amplifier and a loop (a conducting wire encircling the enclosure). The sound of music or the voices of actors are converted into electromagnetic signals. The signals are carried to the loop. A pickup coil fitted in a hearing aid picks up the electromagnetic signals and the receiver in the ear converts this into comprehensible speech or music. Since the hearing aid does not pick up actual sound signals, it receives no ambient noise, ensuring good quality of sound. Other devices include TV listening devices, which allow television sound to be heard at a comfortable level by people with hearing impairments, while not disturbing others in the room.

Recreational items for people with visual impairments include braille playing cards and an audible ball ("beeperball") for ball games. Many of these devices, especially electronic ones, are not available in most developing countries of the ESCAP region. In places where they are produced, they have limited distribution.

Light wheelchairs with a wide base (sports wheelchairs) are important to enable their users to play ball games, such as basketball or tennis, and to dance. This design of wheelchair is, however, more expensive.

11. See United Nations, ESCAP. Promotion of Non-Handicapping Physical Environments for Disabled Persons: Guidelines (ST/ESCAP/1492), New York, 1995, for further discussion of access issues.

12. William G. Brohier, "President's Message", The Educator, Vol. X, No. 1 (Winter 1997), p. 4.

13. For further details and examples, see Human Resources Development Canada. Tips, Tools and Techniques: Home Maintenance and Hobbycraft, People with Disabilities and Seniors Ottawa, 1995.

14. R. Saha and others, "Technology and Employment Opportunities for Disabled in Industry", Indian Journal of Disability and Rehabilitation, January-June 1992.

Box

Box 5: Abdul Matin Mahabub's Story*

|

|

Name: Abdul Matin Mahabub Religion: Islam Age: 38 years Home: Chapain, Savar, Dhaka Education: S.S.C. from Muslimabad High School, Career: 13 years at the Centre for the Rehabilitation Current Post: Head of the CRP Occupational Therapy Department |

In 1980, while working as an electrician in the Power Development Board (PDB), I fell from an electricity pole and broke my back. I came to CRP for treatment and spent three months in the Centre. After treatment I returned to my village. Two years later, the CRP social worker brought me back to the Centre and arranged training in weaving, radio and T.V. repair and poultry rearing. This training lasted one year. Then the CRP appointed me as a Junior Occupational Therapy Assistant. Six years later I was promoted. I worked as a Senior Occupational Therapy Assistant for three years. Now I am working at CRP as the Head of its Occupational Therapy Department.

I, along with other staff of the Department, provide services without which certain essential needs of the patients would be neglected. Our Department is involved in the provision of mobility aids to the patients. The aids are made of locally available materials which are designed to be adaptable to both rural and urban terrains. I assess for needs regarding wheelchair equipment and special splints and give treatment and training for functional independence.

Now I am interested in taking part in workshops and training which will help my Department to further develop. I feel that exposure to others working in similar areas as myself and to new ideas on mobility aids and equipment for disabled people would allow my Department to improve the service we are offering to our patients and disabled people in Bangladesh.

I feel that my own experience and background in working in the field of occupational therapy in Bangladesh would also be helpful to others taking part in similar training.

(* Source: Abdul Matin Mahabub, CRP, Savar, Bangladesh.)

Box 6: Sports Wheelchairs

The Wheelchair Maintenance Clinic in Nonthaburi, Thailand (see Box 8) has modified the design of sports wheelchairs used in developed countries. Sports wheelchairs use high-technology materials, including aluminium alloy and titanium, to make them light and easy to manoeuvre.

The Clinic is currently concentrating on increasing the production of sports wheelchairs for the Seventh Far East and South Pacific Games for Disabled Persons (FESPIC Games), scheduled to be held in Bangkok in January 1999. The Clinic imports main and castor wheels from Taiwan Province of China. The other parts are all produced in Thailand.

Go back to the Contents

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Production and distribution of assistive devices for people with disabilities: Part 1

- Chapter 2 -

Printed in Thailand

November 1997 1,000

United Nations Publication

Sales No. E.98.II.F.7

Copyright c United Nations 1997

ISBN: 92-1-119775-9

ST/ESCAP/1774