ISSUES IN INDIGENOUS

PRODUCTION

The term "indigenous production" is used in the broadest sense in this publication. It refers to the use of local, indigenous knowledge, skills, and methods of production. The most important criterion for production to be considered indigenous is that the production process has been thoroughly assimilated into local conditions by the local people on a sustainable basis.

The choice of a strategy for the production of assistive devices will vary considerably from country to country. Every country will need to consider:

- (a) Economic, social and political priorities;

- (b) Availability of personnel, infrastructure, raw materials, parts and funds;

- (c) Cost of locally produced devices, compared with the cost of importing devices;

- (d) User demand.

In addition to factory-based and other conventional forms of production, the informal sector also produces assistive devices in a decentralized way, often in rural areas. Specific needs motivate families, helpers of people with disabilities and other community members to produce devices with whatever materials and production techniques are available to them. User-specific devices are sometimes produced at workshops for vehicle maintenance and repair. In most cases, they are produced in rehabilitation centres run by Governments, NGOs, hospitals and colleges.

A. User-specific devices

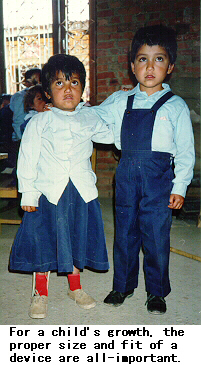

A central issue in production, so far generally neglected, is the extent to which devices are user-specific. An orthosis must be fitted to the size of a user's leg, not simply taken off a shelf. At minimum, a workshop must take specific measurements of the shape of the affected leg and the location or height of various joints.

Although a wheelchair does not require the same degree of precise measurement, it must also be considered a highly user-specific device. Making wheelchairs in one "universal" extra-large size makes no more sense than making clothes in one extra-large size. People are of different sizes, and will therefore require different-sized wheelchairs. This is a problem of particular concern in the Asia-Pacific region, as wheelchairs imported from other regions (often through donations) and designed to fit people in those regions are often too large for local people.

Just like clothes, wheelchairs can still be used if they are the wrong size but they will be uncomfortable and awkward. For children, this could adversely affect their growth and development. Producing "one-size-fits-all" wheelchairs may be useful when a wheelchair is to be used only under special conditions, as in a hospital, or on a very short-term basis, as for a wheelchair temporarily loaned to a user whose regular wheelchair is being repaired. But it would be wrong to assume that such wheelchairs are suitable for long-term, daily use.

B. Appropriate technologies and production methods

International NGOs have made valuable contributions to the initiation and upgrading of the production and distribution of assistive devices in developing countries of the ESCAP region. In some cases, however, the level of technology introduced may be too complex for the countries' current level of infrastructure and support services. In some places, local expertise could not be developed on time to fully utilize the presence of such NGOs.

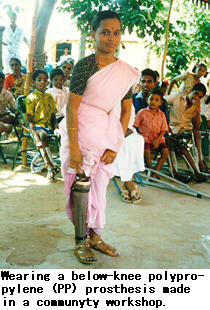

Devices appropriate for the environment of a developing country often use a simpler, less sophisticated technology than the devices adopted in developed countries. Unfortunately, this often leads them to be regarded as inferior, even if their usefulness, durability and ease of repair could make them superior under local conditions.

However, poor methods of production can sometimes result in bad experiences with appropriate technology, which leads people to mistrust appropriately produced devices. The devices produced and the methods of producing them must be at both an appropriate level of technology and a high level of technique: simple, but professional.

Not every device produced within a country's boundaries is necessarily appropriate for use in that country. Some developing countries in the ESCAP region have imported for local use techniques invented in developed countries, without major effort to adapt that knowledge to local user needs. Long-term dependency on foreign expertise in the production of devices and in the import of parts and materials, especially from developed countries, can make devices thus produced much less appropriate for local conditions. NGOs need to take care to ensure that the beneficiaries of their programmes will not be left stranded if the supply of foreign technicians' skills ends.

C. Mass production

Mass production of assistive devices and their parts may help reduce their costs through economies of scale. It may also reduce the time required for production. There is, however, a corresponding increase in the cost and time for distribution, although mass production does allow a wider distribution network to be set up.

In many cases, however, mass production of assistive devices is impossible or undesirable, because it generally requires finished products to be almost identical. Although wheelchairs can be mass-produced, for example, they must still fit the requirements of each individual user. For further discussion see section A on "User-Specific devices" in this Chapter.

Theoretically, devices may be produced using new flexible "just-in-time" methods that would allow them to achieve the economies of scale found in a factory while still being responsive to user requirements. In practice, however, the state of local infrastructure in developing countries makes this difficult. The difficulty is exaggerated by a view, commonly held among producers, that assistive devices are not profitable. Such a system of production might be desirable as a future goal, but at present, it generally makes much more sense for developing countries to decentralize their production systems.

Mass production is most useful for those devices (e.g., vibrating alarm clocks) which do not have to fit a particular set of body measurements. For devices which are user-specific to even a small degree, a decentralized system of production makes it easier for people with disabilities to approach production sites to specify their requirements.

The advantages of mass production could also be realized for some user-specific devices if the mass-produced devices were adjustable. For example, some wheelchairs with adjustable height, footrest position and width are now available.

Even when the finished devices must or should be custom-built, mass production of parts can still reduce costs through economies of scale. Where possible, mass production of parts makes finished devices cheaper, quicker to produce, more easily available, and easier to repair. Producing parts through a machine reduces their variability, thus there is greater assurance of uniform quality.

However, a system of mass production of parts combined with decentralized production of finished devices must be supported by solid distribution networks in order to transport the parts to the production centres. It also requires a considerable investment of capital.

In China and India, there is surplus capacity in some factories producing parts and finished assistive devices.

D. Prescription

Every assistive device must be appropriate for the person who uses it. Even the least user-specific devices, like braillers or vibrating alarm clocks, may not fit well with a user's lifestyle. People who prescribe assistive devices, whether doctors, technicians or community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers, should ask questions of prospective users about their lives, to optimize the chances that the potential users will receive the best devices for their own situations. See Box 13 for a sample list of such questions.

When rehabilitation personnel prescribe devices, it is helpful for them to be able to specify what kind of device is needed. At present, many rehabilitation personnel tend to offer general prescriptions, such as "this person needs a prosthesis", rather than being able to give a specific description helpful for technicians, such as "this person needs an above-knee prosthesis for the lower limb, section socket, tubular system, knee XXXX with brake, and foot 1D10 (dynamic)". A general prescription may result in a device that is unsuitable for the user (e.g., it is too short or too heavy).

This situation is common where rehabilitation personnel know little about assistive devices. There is an unfortunate gap between doctors and other health workers, who know little about assistive devices, and technicians, who know little about the medical or anatomical aspects of disabilities. If the two groups could work more closely with one another and learn something about each other's work, they would be better able to meet user needs.

Prescription must take into account the availability of support services for repair and maintenance, in the long and short term. A device which cannot easily be repaired or maintained is not a good or useful device.

In conditions of poverty in the developing countries of the region, it is unreasonable for prescribers to expect adherence to the strict standards for medical procedures common in developed countries. For example, prosthetists trained in developed countries sometimes have low regard for procedures of amputation surgery in developing countries. It is often said that such surgery is "improperly" performed, as it may lead to scarred stumps or stumps of a non-optimal size. But it is naive to expect that most rural areas will have access to the facilities or skills to perform "proper" amputation surgery and make the subsequent fitting of artificial limbs easier, when many such areas do not even have primary health care services.

It is indeed regrettable that amputation surgery cannot always be performed precisely with a view to fitting a new prosthetic limb. However, at least currently, it is not feasible to change this situation. In the meantime, it is more practical to adapt to the situation. Prosthetists need to accept that most emergency surgery will likely lead to stumps that are not the most optimal for fitting artificial limbs. Furthermore, they need to accept the reluctance of many amputees to undergo a second surgery to mend the stump to a more "acceptable" shape and size. Instead, Asian and Pacific developing countries must develop and use prostheses that can adapt to non-standard amputation procedures.

E. Quality control

In many developing countries of the ESCAP region, interest has recently increased in ensuring the quality of devices produced domestically. Some, including India and Viet Nam, have started to formulate quality-control standards for assistive devices, often similar to those of the International Standards Organization (ISO).

Rushing to adopt such standards is rarely advisable, however. The primary need in developing countries of the region is to produce assistive devices in large enough quantities that everyone who needs a device can get one. High standards may raise production costs (costs that will be passed on to users or to Governments and NGOs). They may also discourage innovation of new products. People often face a choice between a device that does not meet ISO-type standards and no device at all.

This caveat does not preclude the formation of some system of quality control, provided that any such system carefully takes into account local needs and conditions, and that users play a central role in its design. Simply copying a list of standards adopted by developed countries will likely have undesirable consequences.

It is reasonable for a Government to expect a certain level of quality in the devices it provides free of charge to the poor. But this level of quality should be ensured only through withholding of funding, not through legal sanctions. For the Government to impose fines (or more severe penalties) on those who produce devices that do not meet the standards adopted would be an undesirable restraint on innovation, which could hurt more than help people with disabilities. Standards and restrictions which make it illegal to produce adapted motorcycles significantly decrease the mobility of people with disabilities.

The term "quality" should include technique as well as technology. Quality control should ensure that, for example, technicians make devices in exactly the right size for their users and align them properly, as well as requiring durable materials and parts.

High quality alone does not make a device right for its user. The ultimate measure of an assistive device is long-term user satisfaction. A wheelchair produced for a farmer may be of high quality in terms of good technique, the right technology and external appearance, but if the farmer can only do her job with crutches rather than a wheelchair, the "high-quality" device is not a good one for her.

An appropriate system of quality control for assistive devices in a developing country of the ESCAP region will have the following features:

- (a) Be technically feasible and practical in the environments of the majority of users;

- (b) Not contribute to an increase in the cost of devices beyond acceptable limits, in either the short or the long term;

- (c) Not restrict the further development of products;

- (d) Not specify that all devices must have characteristics which most devices currently in use do not already have.

F. NGO-government cooperation

There are many fine examples in the Asia-Pacific region of cooperation between Governments and NGOs in the provision of assistive devices. NGOs have played an active role, with government support, in developing local capacity for the production of assistive devices. Governments often provide the funding, equipment or infrastructure needed for specific NGO-initiated projects. They also help select sites for NGO projects to ensure their sustainability. Governments are also able to support NGO efforts by coordinating diverse agencies to enhance production and distribution. Effective coordination can lead to better dialogue and exchange of information among people in different parts of a country who may be engaged in similar efforts in production or design, including community members and local workshop technicians.

In many cases, NGOs fund small pilot projects and provide technical assistance, often in the form of specialized expertise.

In many Asian and Pacific developing countries, the trend until recently has been for NGOs engaged in rehabilitation to operate only in major cities and their suburbs, without a presence in rural areas. This problem is increasingly being addressed, not least by changes in funding criteria to encourage NGO action in the rural areas and increase rehabilitation services in support of rural communities.

G. Raw materials

Raw materials commonly used in Asian and Pacific developing countries for various types of assistive devices include:

- (a) Aluminium, in the form of tubes and strips (for wheelchairs, white canes and orthoses);

- (b) Steel, in the form of tubes and strips (e.g., for wheelchairs, knee joints, walkers and orthoses);

- (c) Titanium (for prostheses and wheelchairs);

- (d) Wood (for wheelchairs, prostheses and crutches);

- (e) Thermoplastics of different types, such as polypropylene (for prosthetic sockets);

- (f) Polyester resin (for sockets);

- (g) Epoxy and polyurethane (for prosthetic feet);

- (h) Polymethyl methylacrylate (for lenses of devices for people with low vision);

- (i) Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) (for orthoses);

- (j) Nylon, polyethylene (for prostheses and orthoses);

- (k) Natural rubber (for prosthetic feet);

- (l) Glass fibre (for orthoses);

- (m) Carbon fibre (for prostheses, wheelchairs);

- (n) Leather (for shoes, prostheses, orthoses);

- (o) Different types of solvents and catalysts, canvas, cloth and plaster of Paris (POP).

Some countries have chosen to use only indigenously available raw materials. The advantages of this approach are that it is more likely to lead to the development of local capabilities, it is often lower in cost, and there is greater assurance of the supply of the materials. Imports of raw materials and parts, especially from developed countries, can create a level of dependency on foreign expertise and technologies that may prove expensive and unsustainable in the long term.

The disadvantage of this approach is that more effective or efficient materials cannot be used. This means that the devices may be lower in quality, higher in cost, or both. For example, aluminium and its alloys substantially reduce the weight of many devices, but these materials are not available in many developing countries of the ESCAP region. For this reason, there is a general tendency to import at least some raw materials.

Recycling available material is one way to obtain useful raw materials cheaply. Factories in Indonesia and Viet Nam recycle scrap metal from aeroplanes and helicopters into parts for orthoses. Parts of old prostheses are reused in the Philippines. The YAKKUM Rehabilitation Centre in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, uses worn tyres to make rubber parts. However, the Centre found that its recycling programme required improvement to enhance the durability of parts and devices made from recycled tyre rubber.

Care should be taken when introducing a new chemical material. Some may require special safety measures in the process of making a device. PVC, for example, emits toxic fumes when burned. If workers are exposed to resin continuously for a full working day, it can cause headaches or loss of consciousness.

H. Imports

Importing assistive devices can be a way for a developing country in the ESCAP region to provide otherwise unavailable devices. As far back as 1950, the international community recognized the need to facilitate the import of assistive devices, in order to support the education of people with visual impairments. Government signatories to the Florence Agreement on the Importation of Educational, Scientific and Cultural Materials, (opened for signature at Lake Success, New York, on 22 November 1950) agreed to allow easy import of braille documents and other articles for use by blind people.

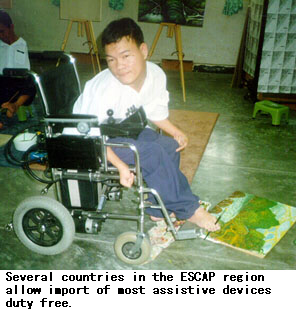

Since then, countries have generally permitted easy import of assistive devices on condition that they be used by people with disabilities. The ESCAP Secretariat recently conducted a survey with a view to possibly including assistive devices in the Bangkok Agreement on Trade Negotiations among Developing Countries of the ESCAP Region, an agreement to reduce trade barriers and tariffs.

Imports from other developing countries are often more suitable than imports from developed countries, especially when the conditions for which the devices were designed resemble those in the importing countries. Devices imported from developed countries in the absence of local needs assessment and capacity-building have usually had the following disadvantages:

- (a) High cost;

- (b) Unavailability of spare parts;

- (c) Lack of local knowledge for repair and maintenance;

- (d) Unsuitability to local physical or cultural conditions.

Prohibitive restrictions on import, such as high tariffs or restrictive legislation, are unlikely to be the best way to deal with these problems. It is more important to ensure that agencies implementing disability policy are aware of these problems and know that expensive, imported high-technology devices are unlikely to be the best choice.

Several countries, including Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Pakistan and the Republic of Korea, allow import of most assistive devices duty-free. Others, including India, Sri Lanka and Thailand, allow duty-free import of assistive devices when the devices are imported by people with disabilities or by organizations working on their behalf. Organizing sufficient proof that the devices are imported for bonafide beneficiaries or their organizations can, however, be a long and complicated process.

China produces most of its assistive devices using indigenous resources, but imports a few parts to produce high-technology devices.

In India, the import of items produced within the country has generally been discouraged. The philosophy has been to encourage the domestic industry and enhance self-reliance. However, in the 1990s, India has begun to liberalize its trade policy and promote foreign investment. This has resulted in the encouragement of imported assistive devices.

In Fiji and Nepal, import duties are compulsory. Nepal charges a one per cent duty on the import of devices by institutions, and a 10 per cent duty on imports by individuals. No duty, however, is levied if the devices are imported for business purposes.

The Philippine Tariff and Customs Code provides no specific exemption for assistive devices. It does, however, stipulate that imported articles of any kind donated to a non-profit organization for free distribution among the poor can be exempted from import duties, if that organization is registered and obtains certification from the Department of Social Services and Development or the Department of Education, Culture and Sports. The devices may not subsequently be sold, bartered, hired or used for other purposes unless duties and taxes are paid. Assistive devices imported for other purposes are subject to tariffs of between 10 and 40 per cent.

Many useful or essential assistive devices are not yet locally produced in developing countries of the region. Since each incremental change brought about by an appropriate assistive device helps expand the capacity of people with disabilities to participate in the lives of their communities, reducing duties and simplifying customs clearance procedures will contribute to improving their lives.

Officials in customs departments are often not well informed about people with disabilities and the devices they require for daily living. They are therefore inadequately equipped to make correct decisions. As a matter of policy, government focal points and NGOs working on disability issues should actively seek to inform customs officers through personal contact with them, the distribution of explanatory information materials, and joint seminars.

22. See the Mandates Supplement for relevant excerpts from these agreements.

23. See the Mandates Supplement for examples of the tariff regimes for assistive devices in selected developing countries of the ESCAP region.

Box

Box 13: Assessment: Key Questions

- How old are you?

- Do you live alone or with others? If the respondent lives with others, ask: In what ways might they be helpful or a problem?

- What is your occupation?

- How far is your house from this workshop? If the distance is more than is convenient for the respondent, ask: How did you get here? Do you plan to go back today? If not, how will you manage overnight accommodation?

- What disability are you looking for help with?

- What caused it? How old were you when this happened?

- Have you had an assistive device before? If the answer is yes, ask: When did you get it and how long did you have it? What were the good and bad aspects of wearing it? Who prescribed it for you?

- What do you expect a new assistive device will be like?

- What do you want to be able to do with it?

The last two questions are especially important. Some potential users may have heard about the availability of assistive devices without knowing how they can personally benefit from one. Others may want a device which is inappropriate for their situation. They may want a motorized wheelchair after seeing one on television, for example, without having considered the resources required for maintaining it.

(Source: Mr. Yann Drouet, Prosthetics and Orthotics Expert, Handicap International Thailand.)

Box 14: Imports Related to Assistive Devices

| Country |

Items imported (devices, parts and raw materials) |

Importing from |

| Bangladesh | Not available | China, India, Norway, Singapore, United Kingdom, United States of America |

| Bhutan | Wheelchairs, walkers, devices for people with visual disabilities, hearing aids, prosthetic feet, knee joints | Bangladesh, India, United States of America |

| Cambodia | Polypropylene sheets, aluminium, stainless steel, pelite, ball bearings, cycle wheels, braillers, prosthetic feet | China, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, United States of America |

| China | High-technology knee joints, prosthetic feet, polypropylene sheet, core plates in integrated circuits, shin assembly of prostheses | Germany, Japan |

| Fiji | Wheelchairs, walkers, walking sticks and daily living equipment | Australia, New Zealand |

| India | Braillers, parts for hearing aids | Germany, Singapore, United States of America |

| Malaysia | Parts for prostheses and orthoses, wheelchairs, hearing aids, devices for people with visual impairments | China, Japan, Taiwan- Province of China, United Kingdom, United States of America |

| Maldives | Wheelchairs, tricycles, crutches, walkers, hearing aids, orthoses, prostheses | China, India, Japan, Singapore |

| Myanmar | Epoxy resin, hardeners, joint bolts and nuts, knee joint, thermoplastics, low-vision aids, teaching aids for blind people, hearing aids, audiometers, batteries | (Information not available) |

| Nepal | Tricycles, artificial limbs, devices for blind people, hearing aids, parts for orthoses | Germany, India, Japan, United States of America |

| Pakistan | Hearing aids, audiological assessment equipment | (Information not available) |

| Philippines | Knee joints, ankle joints, prosthetic feet, shaft for modular prostheses, upper- extremity prosthesis parts, motorized wheelchairs, hearing aids | Germany, Taiwan- Province of China |

| Republic of Korea | Prostheses, braces, hearing aids, electronically operated wheelchairs | Germany, Taiwan Province of China, United Kingdom, United States of America |

| Sri Lanka | Crutches, wheelchairs, calipers | India |

| Thailand | Myoelectric hands, prosthetic feet, knee-shin parts, plastic polyvinyl acetate (PVA), band saw, benzol peroxide, socket routers and duplicating machine | Germany, United States of America |

| Viet Nam | Braillers, thermoplastics for artificial limbs, ball bearings for wheelchairs | (Information not available |

(Source: Country papers presented to the Technical Workshop on the Indigenous Production and Distribution of Assistive Devices held in Madras, India, in September 1995, and information subsequently provided to the Secretariat. "Not available" refers to information not contained in the relevant papers and not subsequently provided to the Secretariat.)

Go back to the Contents

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Production and distribution of assistive devices for people with disabilities: Part 1

- Chapter 5 -

Printed in Thailand

November 1997 1,000

United Nations Publication

Sales No. E.98.II.F.7

Copyright c United Nations 1997

ISBN: 92-1-119775-9

ST/ESCAP/1774