DISTRIBUTION

The distribution of many assistive devices differs from the distribution of commodities which can be picked up from the shelf in a local shop. For user-specific devices, production and distribution need to occur in the same place. For example, orthoses can only be properly produced after the user's measurements have been taken and the user has received proper trials and training.

Assistive-device distribution networks need to be established through central Governments, state or provincial Governments, district administration infrastructure, NGOs, public health centres and rural development channels. These networks need to be supported by people who are technically knowledgeable about disability issues. Financial support for such networks will be required to meet the costs of establishment and operation. Without the requisite policy, programme and funding support, such networks will neither emerge nor be sustained.

While the need to supply assistive devices to poor disabled people is widely recognized, success in meeting this need has so far been limited. Many disabled people cannot afford to pay for assistive devices. In such cases, financial support frequently comes from the Government, although many countries have not yet adopted this principle.

In some countries, the number and variety of devices have increased. However, the majority of people with disabilities still do not have them because there has not been a corresponding improvement in coordination and development of the means to distribute the devices, especially in rural areas. Furthermore, many people who could benefit from assistive devices have no information about the availability of the devices or their potential usefulness.

A. Distribution to rural areas

About 70 per cent of people with disabilities in Asian and Pacific developing countries live in rural areas. They commonly face the following difficulties:

- Difficulties of access to services and facilities (such as those resulting from difficult terrain);

- Lack of infrastructural support (such as the absence of linking roads and public transport);

- Lack of understanding among health-care personnel about disability matters, including confused perceptions of people with disabilities as medical cases rather than as citizens or community members with entitlements;

- Poverty;

- Illiteracy and lack of information about available services;

- Absence or inadequacy of statistics about people with disabilities, especially those in rural communities, for proper planning and programme development.

Villages are situated at varying distances from the nearest rehabilitation centres, which are generally located at the level of the province/state, city or district administration. In large countries, the distance a user must travel to reach the nearest centre may vary from a few to a few hundred kilometres. In addition, a period of at least a week is required to make a prosthesis fit and work properly. Long distances are understandably prohibitive for villagers with disabilities. This is because of the cost involved in travel to and lodging at the centre, as well as the loss of income from work opportunities for those who accompany them.

Various local conditions create further difficulties in distribution. Distances may be smaller in mountainous countries like Bhutan and Nepal, but the time involved in travelling from a village to the nearest centre may be longer because of the hilly terrain. Furthermore, landslides can make transportation extremely difficult and sometimes impossible. Countries composed of many islands, including Indonesia, the Maldives, the Philippines and most of the Pacific island countries, may face difficulties in providing adequate means of water or air transportation to enable poor people with disabilities to travel between islands. Monsoon rains make many villages inaccessible for months every year. Even on the mainland, transportation may be adversely affected in the plains by water logging and deteriorated road conditions.

The aforementioned difficulties mean that a country's system of service delivery should have two major features. First, it must be decentralized. A good transportation and communication system will unquestionably be helpful in distributing devices to local distribution centres. However, with the resources available in most developing countries and the difficulties listed above, it is unlikely that such a system will make centralized production for wide user coverage a realistic possibility.

Second, there should be a large number of local production centres, so that villagers may reach them easily without great expense of time and money. There is currently a tremendous shortage of rehabilitation facilities in rural areas. Many more such centres must be created by Governments, NGOs, and people with disabilities with their families and communities. This effort can be supplemented through rehabilitation camps and mobile clinics.

B. Options for distribution methods and policy

People in Asian and Pacific developing countries have dealt with the above problems in several innovative ways. One approach has been the distribution of disability devices through a camp approach. This approach brings a large number of people with disabilities to a common place (a camp) where they can all receive assistive devices within a short period of time.

Preparatory work for the organization of a camp includes an assessment of needs and the setting of a date for the camp to be organized. Wide publicity is then given.

Camps are usually organized by government agencies and NGOs. The camp approach was first used in India for cataract surgery and immunization, as well as for the prescription and distribution of assistive devices. It is also used in Nepal and Thailand. China has now adopted it for cataract surgery.

Some countries, including Cambodia, extensively conduct mobile workshops. Some NGOs in India have adopted a similar approach, but only in specific and limited areas. A mobile workshop involves a vehicle (such as a van, jeep or boat) which carries within it the necessary tools. The vehicle goes from place to place to provide, repair and maintain devices.

Unlike the camp approach, people with disabilities do not have to travel to reach a mobile workshop. As a result, the mobile-workshop approach is more convenient for people with disabilities and encourages more frequent contact between them and technicians. On the other hand, it involves a greater commitment of resources than the camp approach, especially if production is not decentralized.

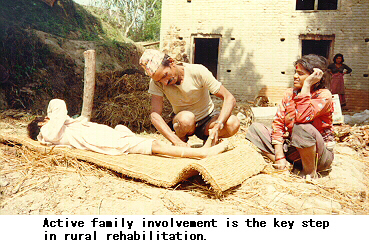

Parent groups in rural areas can provide an important means of supporting the distribution of devices. The parents of children with disabilities in villages close to each other can jointly arrange for rehabilitation facilities to be established with the help of an NGO. Many simple devices can be made in a workshop that local people set up at the village level. Such an approach brings down the cost of rehabilitation.

Providing services in rural areas for assistive devices alone may not be economical or feasible. Instead, integrated multipurpose workshops can be established in clusters or groups of villages to take care of many of the technical needs of the villagers, including but not limited to their needs for assistive devices. These workshops should include multipurpose technicians with knowledge of mechanical and electrical trades who can perform tasks such as those related to energy generation, hand pumps and tube wells, as well as producing, maintaining and repairing assistive devices. People with disabilities, together with village artisans and mechanics, should have a major role in these workshops.

C. Information dissemination

Many people with disabilities who could benefit from assistive devices do not benefit because of a lack of information. Lack of information is a problem faced not only by people with disabilities themselves, but also by their families, community leaders, health and rehabilitation personnel, and NGOs.

Rural people with disabilities have an inherent disadvantage because most information is generated in cities, in a format directed primarily at the educated urban elite. The problem is complicated by low levels of literacy among many people with disabilities and their families (whether rural or urban). Information in directories, manuals or brochures is of little use to them. As a result, they may lack knowledge of the following:

- The existence of assistive devices;

- The devices' usefulness for them;

- Sources of devices;

- Methods by which the devices can be obtained.

There is therefore a need to use existing channels of communication with rural communities to improve their awareness of assistive devices. These channels include:

- Radio and television programmes directed at rural communities, including those used for farm broadcasting and agricultural extension work;

- The information, education and communication channels of primary health care, community development, rural development, gender equity and child service programmes (government and NGO), which could help disseminate basic information on rehabilitation and assistive devices.

Information of relevance to semi-literate or illiterate villagers must be presented in formats and through channels of relevance to them. Multiple channels may be used to convey the information and reinforce newly-acquired knowledge. Distance learning programmes, folk theatre and poster campaigns are among the channels which could be employed for mutually reinforcing effect

D. National policies on distribution

The number of government agencies involved in the distribution of assistive devices in Asian and Pacific developing countries varies from country to country. Some Governments fund NGOs or government agencies to distribute and supply assistive devices to users. A large number of agencies could make it easier to reach large numbers of people.

In some developing countries of the region, activities related to the distribution of assistive devices (e.g., registration of users, allocation of funds, follow-up services) are spread among more than one government agency or NGO, with inadequate communication or cooperation among them. This multiplicity of agencies and NGOs and lack of communication may render the process of coordination complex and difficult to manage. It may also result in conflicts in decision-making or implementation. Poor people with disabilities stand to lose the most, as this problem may result in their not receiving the assistive devices they need easily, quickly, and at prices they can afford.

Cambodia relies heavily on NGOs for distribution of assistive devices; all of its workshops are run by NGOs. Government and NGOs work closely with each other. People with disabilities can approach any of the workshops and receive devices free of charge. There is currently no system of registration in Cambodia, but there is a proposal for starting such a system in the country's newest rehabilitation plan. Local-level government offices for social affairs hold monthly meetings with commune and village leaders in order to inform people with disabilities about the services available. Some centres are equipped with dormitories. Most centres give meals to patients. Many also give them an allowance to cover the cost of transport.

In China, people with disabilities must pay for assistive devices. Different models of devices are available at different prices. This means that poor people with disabilities are often not able to afford the devices they think suit them best. People with disabilities must get their prosthetic and orthotic devices at provincial centres. Each recipient must spend a few days there before receiving a device. Near each such centre there are some arrangements for the accommodation of people with disabilities and their family members, who must meet the costs themselves. China's Ninth Five-Year Plan has introduced a system of loans for rehabilitation to cover these costs.

Distribution of prostheses and orthoses in India involves both governmental and non-governmental systems. People with disabilities or their families can receive assistive devices free of charge, or at a 50 per cent discount, if their monthly income is below specified limits. To receive devices at these concessional rates, a disabled person must have an income certificate to approach a centre which receives Central Government assistance. They are also entitled to some allowances for travel, lodging and food, but these allowances are usually insufficient to cover the full costs. Users usually have to return after a few weeks to obtain their devices. One problem with the Indian system is that there is usually little planning for follow-up sessions. Follow-up is often not even possible because of the lack of trained personnel. There is no registration of those who seek or receive devices.

In Malaysia, people with disabilities must register themselves with the appropriate government agencies. Those registered are entitled to get assistive devices free of charge from centres specified by the Government. They can also obtain the devices free of charge from private workshops, if a device is not available at the specified centres. Furthermore, those registered are paid the cost of board and lodging when they come to the centres to obtain their devices.

The Government of Pakistan provides prostheses and orthoses free of charge to those who apply to the National or Provincial Rehabilitation Centres. It also provides hearing aids free of charge to children, but not to adults.

Sri Lanka provides devices through government agencies and NGOs. The Friend-in-Need Society of Colombo has a programme to provide the Jaipur prostheses to amputees, especially in rural areas. Those who cannot pay for the prostheses can receive them free of charge. Costs are covered by local donations and international aid.

In Thailand, people with disabilities who are registered with the Department of Public Welfare (or its provincial representatives) are entitled to a range of free services, including assistive devices. There are, however, significant difficulties involved in registration.

First, an essential condition for registration in Thailand is the holding of a medical certificate of disability. The Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons Act (1991) does not specify that only government hospitals can issue those certificates. In practice, however, many doctors are reluctant to issue them, even those in government hospitals. Training for doctors to enable them to assess disabilities is not widespread, and does not give doctors the confidence to undertake assessment and certification. The certification form is complicated and difficult to complete. Doctors who have received training for disability assessment generally do not share their training experience with others in their respective hospitals. Those trained are not necessarily the ones who are assigned to assess and certify disability.

Faced with such obstacles, few can obtain the certificates required for registration and free assistive devices. This situation is under review in Thailand, with a view to simplifying the process. However, such obstacles are not unique to Thailand.

The second difficulty involved in registration is that most people with disabilities who need free devices cannot afford the expense involved for transport, board and lodging at provincial capitals where the registration process takes place, although poor people can seek assistance for this.

Diverse agencies are involved in supplying assistive devices in Thailand. The Ministry of Health has principal responsibility for distributing devices, the Department of Public Welfare is responsible for registering people with disabilities, and the Ministry of Education distributes certain devices for schoolchildren. A Rehabilitation Fund, established under the Rehabilitation Act, is available for meeting the costs of repair and spare parts.

In Viet Nam, orthopaedic devices are traditionally the responsibility of the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA). Some units are now being set up under the Ministry of Health Services. Poor people with disabilities and those who acquired disabilities in war receive their devices free of charge, but others must pay for them. Most users must go to