REPAIR AND MAINTENANCE

It is a waste of time and resources to provide a person with an assistive device if that device breaks down after a short period of time and cannot be repaired or replaced. Repair and maintenance of assistive devices is a crucial part of any strategy to achieve equality of opportunity for people with disabilities.

The term "repair" refers to modifications made to a device when it is in poor or no working condition, in order to make it work properly again. "Maintenance" refers to the modification or replacement of parts made to prevent possible failures while the device is still working properly, in order to prevent repair from being necessary. Both functions can be performed by users themselves with or without the help of others with mechanical skills. Repair work is more likely to require the help of mechanics or technicians.

The ease of repair and maintenance depends partly on the design of devices, and partly on the availability of infrastructural and technical support near the users. Without some state aid, this support will grow only with time, economic progress and market demand which may not be primarily defined by the needs of disabled people.

Imported devices are typically the most difficult to maintain and repair, partly for lack of components, but also because manufacturers often do not supply instruction manuals for this purpose. Users may not even know that such documents exist, especially when they purchase the devices. India has faced this problem with respect to braille presses and computerized braille printers.

If people with disabilities and their helpers receive adequate instruction on the maintenance of their devices when they receive them, much less time and effort will have to be spent on repairs. Prolonged exposure to humidity, dust, sand, mud, heat, water and sunlight can cause problems such as corrosion, increased friction in moving parts and hardening of thermoplastics through ultraviolet radiation. Maintenance tips (see the Technical Specifications Supplement) will help users increase the lifespan of their devices and ultimately lower the costs.

A. User acceptance of devices

People with disabilities need a transition period to get used to their assistive devices before they can accept the devices as a part of their lives. This period may vary from a few weeks to a few months, while an individual user decides whether a device is suitable for the way of life she or he wants to lead.

Currently, when a camp approach is used for distributing prostheses in developing countries of the ESCAP region, a second or a third camp for follow-up is usually not held. But follow-up is crucial in the transition period and the period immediately after it, as even a short period in which devices do not function properly may make their users ultimately decide the devices are not worth the trouble.

Many users of hearing aids, for example, stop using them when they have to replace batteries and cords, which are not easily available in rural areas. Similarly, breakage of orthoses among children is usually high. In itself, this may be a good sign, as it indicates that the children have really been using the devices. But if the breakages are not dealt with quickly, children may stop using the orthoses and revert to moving as they did before the orthoses enabled them to become more active.

The use of orthoses requires even more follow-up, with closer attention to detail, than the use of prostheses. An old prosthesis will not work as well as it used to if a child wearing it outgrows it but an old orthosis, in the same situation, will not work at all.

In one case, a user brought a prosthesis back to the rehabilitation centre after seven years, during which time he had been trying many different methods of repair, as he had had access neither to a repair facility nor to a replacement prosthesis. The result is shown below:

B. Cost of repair and maintenance

Cost often deters many people with disabilities from getting their devices repaired or maintained. Many developing countries of the ESCAP region have schemes for providing assistive devices to people with disabilities, or at least those able to obtain the necessary official papers, at concessional rates (see Chapter VI for examples). They do not, however, usually offer a similar subsidy for repairs. As a result, poor people with disabilities find it extremely difficult to afford new parts or new devices. If workshops are far away, the costs of transportation, board and lodging become a further barrier.

Malaysia and Thailand have adopted a policy of subsidizing the cost of repair, replacement and maintenance as well as that of the initial devices. This is helpful, and would be still more so if two more steps were taken to ensure the success of the policy. First, this support must be provided in a manner that is decentralized enough to reach users. Second, people with disabilities need adequate information about where to receive the support.

The cost of repairs is not only monetary. It also involves the time spent repairing devices. In Thailand, repairing hospital wheelchairs has typically taken days or even weeks while technicians wait for spare parts to be delivered. In the meantime, no temporary replacement is available, leaving users immobile for a long period. This results in severe disruption of users' lives. It could be prevented if wheelchairs were loaned to users while they awaited repairs. Loaning of prostheses and orthoses would be inappropriate, but loaning of less user-specific devices would be acceptable, as those devices would only be used for a short period. See Box 8 for a description of an NGO that has attempted this latter solution.

C. Repair and maintenance in rural areas

Repair and maintenance are not, of course, entirely rural problems. Devices like computerized braille embossers, text reading machines, and stair lifts are often difficult to repair even in cities and towns. The reasons can be non-availability of spare parts, lack of local technical skills, or both.

Nevertheless, more emphasis must be placed on the development of repair and maintenance services in rural areas, for reasons outlined above: most people with disabilities in the region live in rural areas; rural areas are deprived of repair and maintenance services because it is more difficult for such services to reach them; and assistive devices are subjected to far more strain in rural than in urban areas.

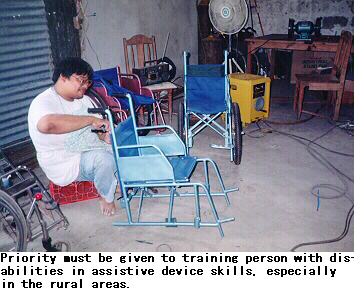

Local mechanics and artisans can repair some devices, although they may require additional equipment and training (see Chapter VIII for details). Another problem is that mechanic workshops are not always available near users in rural areas. The only alternative this leaves is for users to go to the rehabilitation centre where they obtained the devices, which is a deterrent. Ideally, it would be best to have such a workshop provide the requisite services within a radius of one to two kilometres from each user. While it is often not practical to set up that many new workshops specifically for this purpose, it may be feasible to identify enough existing workshops that, with proper technical inputs, could provide the services required by most assistive-device users.

When local mechanics and artisans are not nearby or are not capable of repairing a particular device, mobile workshops may be of great help (see Chapter VI, Section B, for a description of the mobile-workshop approach). Countries which use the mobile-workshop approach for repair and maintenance include Cambodia, India and Thailand. In Cambodia and India, NGOs provide their services through mobile workshops.

Box

Box 15: KAMPI's Wheelchair Projects*

For the past several years, KAMPI and other organizations of disabled people in the Philippines were largely dependent on used appliances, particularly wheelchairs, donated by other countries for use by their members. But these wheelchairs tended not to last because they had not been made to endure the harsh road conditions in the Philippines, especially the rural areas.

There has been increasing interest on the part of governmental agencies and non-government organizations in donating wheelchairs to organizations of disabled persons. Assistive devices from such sources are usually purchased in bulk from commercial establishments; some devices are even imported.

KAMPI's "think-tank" saw the feasibility of raising seed money to start small wheelchair production projects to be undertaken by organizations of disabled persons. The projects would aim both to raise funds for the organizations and to provide people with disabilities a source of livelihood.

In 1995, the Asahi Shimbun Welfare Organization of Japan, which has been donating used wheelchairs, contacted KAMPI concerning its interest in contributing expertise to teach KAMPI members the skills of making wheelchairs using local materials.

KAMPI wrote a project proposal to the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) requesting matching funds for the costs of board and lodging for 12 trainees. The Asahi Shimbun Welfare Organization met the expenses of the Japanese trainer and the materials used in the one-week training.

The DSWD provided the matching funds requested and KAMPI selected the participants from organizations of disabled persons who were interested in initiating a wheelchair production project in their respective communities as a follow-up to the training.

Two months after the training was conducted in November 1996, the Association of Disabled Persons of Iloilo Province, a KAMPI affiliate, started producing low-cost wheelchairs.

A few months later, the Association of Disabled Persons of Negros Occidental, another KAMPI affiliate, also started to produce its own low-cost wheelchairs.

The wheelchairs of the above-mentioned KAMPI affiliates are made of materials which can be purchased from any local bicycle store. The frames are of steel tubes and the wheels are bicycle wheels. Common repairs can usually be made by a local welder or mechanic.

Compared to the quality of commercial wheelchairs, the KAMPI-produced wheelchairs are sturdier and cost approximately US$135 per unit.

With KAMPI's present limited capital, on average, the output is only 30 units per month.

The national KAMPI office has, however, requested the DSWD to purchase KAMPI wheelchairs when it next makes its annual wheelchair purchase in 1998. As there is still a need to further improve on the quality of the wheelchairs produced, KAMPI will organize another training programme in November 1997, under the auspices of the Asahi Shimbun Welfare Organization.

KAMPI plans to start two other projects in this series in the province of Cagayan in the northernmost part of Luzon and Cagayan de Oro City on the island of Mindanao. Both projects will be undertaken through a partnership of the local KAMPI chapters and local government units.

Thus far, there are very few women (only three) involved in the wheelchair projects. The workers are nearly all disabled men deaf and orthopaedically handicapped men are the core workers.

KAMPI hopes to increase the number of women involved in wheelchair production in the future.

Go back to the Contents

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Production and distribution of assistive devices for people with disabilities: Part 1

- Chapter 7 -

Printed in Thailand

November 1997 1,000

United Nations Publication

Sales No. E.98.II.F.7

Copyright c United Nations 1997

ISBN: 92-1-119775-9

ST/ESCAP/1774