Planning and Building Design Recommendations

A. Introduction

This chapter of the guidelines will address approaches to the planning and designing of accessible environments for persons with disabilities and elderly persons.

The creation of new physical elements, such as transport infrastructure, neighbourhoods, or individual buildings, is always preceded by planning, design and decision-making.

Depending on several national and/or local factors, as well as the size of the project, the level of technical complexity and the stage of administrative development, this process varies. It may be regulated by legislation, directed by complete administrative measures and professional undertakings, or it may be realized through informal actions.

In societies which guarantee accessibility, this process is characterized by well-established polities with built-in prerequisites such as:

- A complete legal system (from law to standards);

- A full set of instruments (e.g., master plan, town plan, detailed plans);

- Administrative effectiveness (from permission o control);

- Professional undertakings (from guidelines to expertise);

- Political transparency (openness of information, and public attendance and involvement); and

- Democratic control (from awareness to participation).

In a long-term strategy, it is desirable to integrate access issues in the formal process of planning and decision-making at all levels. A short-term strategy would be to identify appropriate points in which to intervene in existing systems.

In most developing countries in the ESCAP region, the physical planning and design process is under development. There is scope for strengthening administrative and/or democratic control in that process. A general strengthening of the planning and design process concerning a wide range of social factors, such as shelter, health, security, equality and environmental protection, has to go hand in hand with the implementation of access requirements in the planning system.

The planning and design process in most countries is governed by a series of administrative instruments. Normally, these instruments are named:

- Regional plans;

- Master plans;

- Town/urban plans;

- Building permission documents; and

- Construction documents.

Depending on the political and administrative system, these documents have different functions and status. Access issues are related in different ways to these levels of planning and to the legal status of the instruments. Access legislation as well as different strategies and actions must also relate to these instruments and their administrative functions.

The guidelines become effective only if they conform with the decision-making process and the distribution of authority and power built into this process.

As many ethnic, cultural, social and economic differences and prerequisites prevail in the ESCAP region, there is a danger that generalizations in the design recommendations may be too general. Even if the basic principles of accessibility are universal, the applications and technical solutions need to be adapted to national and even local specificities.

The difference between urban and rural conditions is stressed in this chapter. But even those terms mean different things in different areas: the term "urban" can refer to high rise buildings, but lso include squatter areas.

This chapter contains design recommendations for accessibility, with examples of solutions already used or recommended in the region. The gaps are many and the recommendations may be considered as provisional.

Safety requirements may need to be reviewed. Stringent demands for safety are often used as grounds for excluding persons with disabilities and elderly persons.

Resources for and competence in undertaking research on access issues in the ESCAP regions as well as related exchanges of information need to be strengthened. Access research must be accepted as an important multi-disciplinary activity requiring, inter alia, applied research on accessibility.

Requirements for building and related structures and design recommendations are contained in Annexes I and II, respectively.

B. General considerations

1. Definitions: impairment, disability and handicap

The World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons recognizes that disabled persons do not form a homogenous group. In 1980, the World Health Organization adopted an international classification of "impairment", "disability" and "handicap". There is a clear distinction among these three. Previous terminology to define these terms reflected a medical or diagnostic approach. The new definitions represent a more precise approach.

People with visual, hearing and speech impairments and those with restricted mobility or with so-called "medical disabilities" encounter a variety of barriers. From this perspective of diversity in unity, it is useful to clarify the distinctions among three commonly used terms.

- An impairment is any loss or abnormality of psychological, physiological or anatomical structure or function. An impairment can be temporary or permanent. This includes the existence or occurrence of an anomaly, defect or loss in a limb, organ, tissue or other structure of the body, including the systems of mental function.

- A disability is any restriction, or lack of ability (resulting from an impairment), to perform an activity within the range considered normal for a human being. A disability may be temporary or permanent, reversible or irreversible, and progressive or regressive.

- A handicap results from an impairment or a disability and limits or prevents the fulfilment of a function that is considered normal for a human being. A handicap is therefore seen in the relationship between disabled persons and their environment. Cultural, physical or social barriers to mobility within the built environment are handicaps.

2.General planning and design considerations

No part of the built environment should be designed in a manner that excludes certain groups of people on the basis of their disability or frailty. No group of people should be deprived of full participation in and enjoyment of the built environment or be made less equal than others due to any form or degree of disability. In order to achieve this goal adopted by the United Nations, certain basic guiding principles need to be applied.

- It should be possible to reach all places of the built environment;

- It should be possible to enter all places within the built environment;

- It should be possible to make use of all facilities within the built environment; and

- It should be possible to reach, enter and use all facilities in the built environment without being made to feel that one is an object of charity.

These basic guiding principles may serve as general requirements for consideration in physical planning and design. These requirements may be summarized as follows:

- Accessibility

The built environment shall be designed so that it is accessible for all people, including those with disabilities and elderly persons. - Access or accessible

This means that people with disabilities can, without assistance, approach, enter, pass to and from, and make use of an area and its facilities without undue difficulties. Constant reference to these basic requirements during the planning and design process of the built environment will help to ensure that the possibilities of creating an accessible environment will be maximized. - Reachability

Provisions shall be adopted and introduced into the built environment so that as many places and buildings as possible can be reached by all people, including those with disabilities and elderly persons. - Usability

The built environment shall be designed so that all people, including those with disabilities and elderly persons can use and enjoy it. - Safety

The built environment shall be so designed that all people, including those with disabilities and elderly persons, can move about without undue hazard to life and health. - Workability

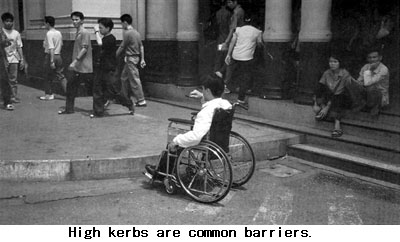

The built environment where people work shall be designed to allow people, including those with disabilities, fully to participate in and contribute to the work force. - Barrier-free or non-handicapping

This means unhindered, without obstructions, to enable disabled persons free passage to and from and use of the facilities in the built environment.

3.Access needs of diverse disability groups (*1)

In order to create fully accessible environments, it is important to understand the nature of the access requirements of diverse disability groups. For the purpose of built-environment design, there are usually four major disability groups:

- Orthopaedic: ambulant and non-ambulant (wheelchair users);

- Sensory: visual, hearing;

- Cognitive: mental, developmental, learning;

- Multiple: combination of any or all of the above.

(a) Orthopaedic

People with orthopaedic disabilities are generally those with locomotor disabilities which affect mobility. This can mean impairment of the trunk, the lower limbs, or both of these. People with orthopaedic disabilities may also have impairment of the lower limbs and the trunk as well as the upper limbs. People with orthopaedic disabilities are divided into two subgroups, namely;

- Ambulant disabled persons are those who are able, either with or without assistance, to walk and who may walk with or without the aid of devices such as crutches, sticks, braces or walking frames.

- People who use wheelchairs are unable to walk, either with or without assistance, and who, except for the use of mechanized transport, depend solely on a wheelchair for mobility. They may propel themselves independently, or may require to be pushed and manoeuvred by an assistant. While being unable to walk, the majority of people in this group are able to transfer to and from a wheelchair. The built environment needs to incorporate level access, ramps, lifts/elevators, handrails and grab bars, larger toilet cubicles, clear signs, sufficiently wide paths, doors, entrances, lobbies and corridors. The presence of these features would ensure wheelchair users access to buildings and to the external environment.

(b) Sensory

People with sensory disabilities are those who, as a consequence of visual or hearing impairment may be restricted or inconvenienced in their use of the built environment. They are divided into twosubgroups:

- Visually-impaired/blind persons who rely solely on their sense of hearing, touch and smell. The built environment must therefore incorporate certain aspects of sound, texture and aroma to assist these persons in their surroundings.

- Hearing-impaired persons who rely solely on their sense of sight and touch and need signs, colour and texture to be incorporated in the built environment to assist them in moving around their surroundings.

(c) Cognitive

People with cognitive disabilities are generally those with a mental illness, a developmental or a learning disability. To assist them to function in their surroundings, the built environment should incorporate a combination of cues such as those of sight, touch and sound, as well as signs, colours and texture.

(d) Multiple

People with multiple disabilities are generally those with a combination of orthopaedic, sensory and/or cognitive disabilities. The built environment therefore must incorporate a combination of visual, tactile and olfactory cues to assist them in their use of their surroundings.

4. Specific needs of diverse disability groups

In the planning and design of barrier-free environments, it is essential to ensure that suitable access and facilities are provided for people with all the disabilities mentioned above. Identifying and understanding the circumstances which create barriers for persons with disabilities and elderly people is a fundamental requirement. A systematic review of layouts, space requirements and the use of components and component relationships may need to be undertaken to evaluate the adequacy and performance of design proposals.

(a) Mobility-impaired people

In terms of circulation, wheelchair movement is seen as the most critical. The spatial needs of the ambulant disabled and the sensory or cognitive disabled are unlikely to exceed the space needed to manoeuvre a wheelchair.

Independent wheelchair users require more generous activity space width, while assisted wheelchair movement requires greater length or depth of space and, consequently, larger overall turning space. The built environment should accommodate both independent and assisted wheelchair mobility.

The recommendations in this publication are suitable for most standard, manually propelled chairs and electric indoor wheelchairs. Electric outdoor models generally require 10 to 15 per cent more manoeuvring space than standard, manually-propelled chairs.

(b) Visually-impaired people

Many blind people, including those who are registered as such, have varying degrees of residual vision. The following recommendations pertain to people who are totally blind and those who have low vision:

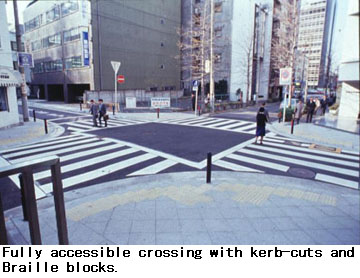

- Dropped kerbs to footpaths: Interruptions in footpath kerbs and edges are useful cues for partially-sighted people. Where interruptions do occur, they should be indcated with tactile paving.

- Stairs and ramps: Handrails should be of a bright colour, contrasting with the surroundings. They should extend a minimum distance of 300 mm beyond the top and bottom of the ramp or stairs to give a blind person a chance to feel them before encountering the hazard. Staircases should have bright contrasting, preferably non-slip nosings. A tactile warning surface should also be incorporated into the floor at the top and bottom of the staircase or ramp.

- Walkways: These should be fitted with visual signs and tactile clues (e.g., Braille blocks) as route finders. It is desirable to define clearly the edges of paths and routes by using different colours and textures. It is also possible to use plants to emphasize pavement edges, but care must be taken in the choice and placement of plants to avoid people tripping over. Large featureless paved areas in front of buildings should be avoided as these can cause glare problems for visually-impaired persons and make it difficult for them to distinguish entrances. Patterns in the paving should be carefully thought out to guide people through routed areas or to entrances. Regular bands of colour at 90 across narrow pathways should also be avoided as persons with impaired vision can easily mistake these for steps.

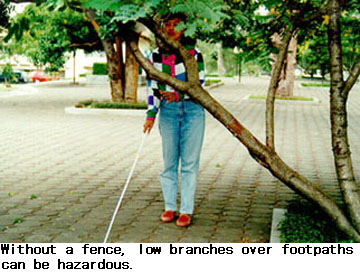

- Hazards: Windows and doors opening outwards can be very dangerous. One solution is to recess outward opening doors into a porch. Street furniture, trees, lamp posts, fire hydrants, waste bins, flower tubs, seats and other such items should be located to one side of pathways and roads used by the public. Some of these could be grouped together with a change in paving surface texture and colour to give some warning on approach. The use of contrasting colours can greatly assist visually-impaired persons particularly on street signs or lamp posts. A contrasting band at eye level should be incorporated onto the posts. Overhanging awnings or signs should be positioned well above 2 metres. Low barriers should be placed around temporary road works to enable persons using canes to detect the hazards.

- Tactile objects: The sense of touch is vital to people with visual impairments. Objects which are important in daily life should be distinctive in shape, texture or size. Coins and bank notes should be so designed that the value of each may easily be identified.

- Signs: These should be in contrasting colours. Raised letters and characters should be used to allow blind persons to feel the signs. Where possible, universally accepted symbols and colours should be used, e.g., green for safety, yellow or amber for risk and red for danger. A clear system of signs should be used throughout a building, with a similar height and format at each change in direction. Signs should be fixed at eye level when mounted on a wall; a suspended sign should be hung between 2 m and 2.4 m above floor level.

- Hedges and trees: Such plants must be maintained to prevent them from encroaching onto footpaths. Low branches hanging over footpaths should be removed.

- Doors: The use of colour to distinguish doors from surrounding walls is very useful. A colour contrast between a door and a door frame, with the door handle in a distinct tone, can be of great benefit to people with visual impairments. Glass doors must have a bright coloured band or motif at eye level to avoid partially-sighted persons from walking into them.

- Corridors and circulation: All appliances and fittings should be recessed where possible.

- Lifts: Raised numbers with tactile indications on landings should be used to indicate the floor. Buttons in the lift car should be marked with raised numbers and Braille (on control buttons). A voice synthesizer is th most important addition to any lift serving more than two floors and can give to visually-impaired persons important information such as: doors closing/opening; lift going up/down; lift free; and floor level.

- Summary recommendations for visually-impaired people:

- The use of Braille guide blocks should be promoted and installed in public facilities, including train stations, shopping centres and bus terminals.

- Glare should be reduced from windows by using net curtains, solar reflective glass, or external/internal blinds.

- Contrasts should be reduced between the outside and inside of buildings. Windows should not be positioned to cause silhouetting in corridors and circulation areas unless the possibility of glare is reduced by one of the above measures or by other means.

- Changes in colour and texture should be used to warn of differences in floor level and to indicate door handles, light switches and other fixtures.

- Green and blue tones being hard to differentiate (for example, green carpets and blue walls can appear as one to a visually-impaired person), they should be avoided. The red colour range causes the least difficulty in this respect.

- Patterns should be used to indicate direction warning. A contrasting band of colour on walls can be very helpful, e.g., a line of contrasting tiles in a tiled toilet area can help to define walls to visually impaired persons.

(c) Hearing-impaired people

- Lifts: It is important for the emergency call button in lifts to have an acknowledgement light adjoining it. This provides both visual and auditory notification that someone is in trouble in the lift and that someone is dealing with the problems.

- Fire evacuation: It is most important that it is widely understood that a person with a hearing impairment will react a lot more slowly than someone without this difficulty.

- Visual signs: These must be very clear and accurate. A flashing light unaccompanied by a message can be confusing (e.g., a flashing fire exit sign would be preferable to a flashing red light; it gets the message across much more quickly). Flashing exit signs in public buildings are preferable to permanently lit exit notices in emergency situations. These will be activated only when alarms sound during an emergency. Signs in ll facilities frequented by members of the public, including shopping and entertainment areas, should be improved. Electric and flashing information signs to indicate stops should be installed on trains and buses to enable deaf persons to use public transportation independently.

- Good lighting and prevention of glare: These are as important for people with hearing impairment, who focus on facial expression, as for those with visual impairment. Many people lip read. Flat lighting and conditions that remove contouring should be avoided. A flexible installation to suit the context and avoid any flattening effect, with a good combination of general and localized lighting, is better than high overall levels of lighting.

- Alarm systems: Bedrooms used by people with disabilities and elderly persons should be provided with flashing lights activated by alarm systems to alert them in the event of an emergency. Vibrating pillows linked to an alarm clock or an alarm system are a further possibility for awakening hearing-impaired persons.

- Hearing aids: Wherever possible (e.g., in foyers, meeting rooms, interview rooms, courts, theatres, training venues, booking offices and cash desks) an induction loop system should be installed. These can, however, cause problems of "overspill" (when people in adjoining rooms wearing hearing aids can overhear conversations in other rooms). The use of magnetic tape under carpets can reduce this effect. Infrared systems can provide a solution where confidentiality is required, but these have other drawbacks.

- Background noise: It is most important to reduce any background noise both internally and externally, for instance, a magnetic hum can be created by mechanical ventilation systems or by fluorescent lighting. These problems should be solved by mechanical and electrical engineers.

- Acoustics: Care should be taken to provide good acoustic conditions in all building interiors. Sound absorbent surfaces should be utilized to minimize reverberation which could seriously affect the hearing of a hearing-impaired person. In areas where there is fixed seating, such as lecture theatres, the lecturers position should not be in front of a window or the light source which may create glare and cause difficulty in lip reading.

C. Planning and design recommendations

Opportunities for people with disabilities to participate in all aspects of the public and working life of the community are being progressively broadened. Persons from diverse disability groups may attend and use public and private buildings as visitors, residents or staff members. They may be alone or be accompanied by others. Whatever the circumstances, the planning and design of any built environment should provide a barrier-free setting to enable all staff, residents and visitors to circulate safely and comfortably.

Depending on the type of disability, many different planning and design consideration are required. The following general guidelines are recommended, and attention is drawn to Annexes I and II.

1. General requirements

The ideal situation that should be aimed for in all buildings is to provide reasonable means of access for all people whatever their specific requirements may be. This applies from the boundary of the site or car park to the main entrance/exit of a building. The purpose of access should be to encourage movement throughout the building with sufficient space for wheelchair manoeuvres and convenient ways of moving from one floor to another. An accessible environment should also have provision for persons who are deaf or who have sight impairment to enable them to find their way around the building and to use the facilities provided within the building.

2. Public transport

(a) Land transport

Buses, trams, taxis, mini-buses and three-wheelers should be designed as far as practicable to include facilities which can accommodate people with disabilities. New vehicles when purchased should comply with accessibility standards to enable all people, including those in wheelchairs, to use the service provided. Equally important, travel routes to bus stops should also be barrier-free to ensure that persons can travel from their homes to their chosen pick-up point. Training should be provided for drivers to help them become aware of the needs of persons with disabilities.

(b) Rail transport

Whether overground or underground, rail travel is a highly effective mode of transport. Every train should contain fully accessible carriages. Staff should be trained in methods of assistance and be at hand on request. Stations for all rail travel should be fully accessible with extra wide turnstiles where possible. Staff should be on hand to assist persons with disabilities to enter or exit through convenient gates. All new railway stations should be designed to be fully accessible. In a situation where full accessibility is not secured at the initial construction stage, it is imperative to design the layout of the station in such a manner that access features can be easily modified at a later stage.

(c) Water transport

All forms of water transport should be accessible to those with disabilities and infirmities. Ferries should be fitted with accessible ramps. Within a cabin space should be set aside for securing a wheelchair in a position for comfortable integration with other passengers. Piers should be fully accessible and have simple boarding and disembarkation procedures. Careful design and planning can preempt problems.

(d) Air transport

All domestic, short-haul aircraft should have the capacity to safely accommodate at least one wheelchair passenger. All national and international airports should be fully accessible and have appropriate boarding facilities. Special attention should be given to accessible toilet facilities on board aircraft.

3. External environment

Public places such as parks, gardens and zoos should be fully accessible to persons with disabilities and infirmities. This is vital if discrimination is to be avoided. The current unbalanced situation needs to be addressed so that persons with disabilities may freely move in the external environment as part of their integration into society. Parking facilities, obstructions on pavements, street furniture, pavements, crossings, changes in level, ramps, steps, plants and landscaping, signs and symbols, gratings and covers all need careful consideration.

4. Public buildings

All public buildings such as offices, shops, factories, schools, universities, hotels, restaurants, bars, cinemas and theatres should have accessible entrances and exits. Horizontal and vertical circulation and all facilities contained within buildings should also be accessible for persons with disabilities. Wherever possible, an accessible service window should be introduced in a public building to facilitate assistance which may be required.

5. Housing

Entry to, and movement within buildings must be carefully considered when designing housing. Height and layout of fixtures in each house can be tailored or adapted to suit the needs of the resident. An adaptable housing concept should be promoted, in particular, for homes financed by government housing loans or public housing schemes (see section E.3, Adaptable housing).

6. Information technology

The use of modern technology should be encouraged among blind, deaf and home-based disabled persons, to facilitate communication from within the home. Communication with others can greatly enhance an individuals self-esteem by opening up new possibilities for developing higher levels of social and other skills, thereby enhancing self-reliance and independence.

Telephones should be installed with push buttons incorporating large numerals and volume controls. Some telephones have a facility for visual display of messages. Various types of induction loop systems are available to allow persons who have impaired hearing to hear public performances, take part in discussions or even to watch television. Visual and audible alarm systems and paging systems can be used within or outside of buildings. Computer aids are available to assist people with disabilities. Many such aids open up employment opportunities for persons with disabilities.

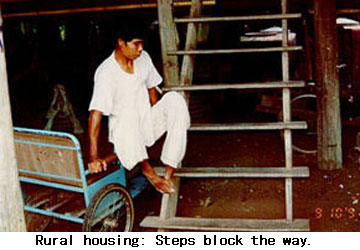

7. Rural requirements

The majority of people in the Asian and Pacific region live in rural areas. In the coming decade, notwithstanding rapid urbanization, there will be a higher increase in absolute numbers of the rural population. Higher rates of mortality and morbidity, a lower rate of literacy and a higher incidence of poverty and deprivation characterize rural communities, placing them in a less advantageous position than their urban counterparts.

Furthermore, while several basic amenities such as piped water supply, sanitation, toilets and access to the mass media (e.g., radio and television) are available to urban residents at the household level, in rural areas, these are often available only as community amenities.

The urban built environment includes modern public facilities for education, training, employment and self-employment, as well as entertainment. In contrast, the rural built environment includes standpipes and wells, village dispensaries, primary schools, community toilets and water tanks, village markets, agricultural extension centres and village or district administrative institutions. These facilities have an impact on the daily lives of people in the rural areas. The extent to which the facilities are accessible and usable by persons with disabilities and elderly people determines their integration into rural community life.

Some of the issues faced by rural disabled persons and elderly people are: non-accessible paths, roads without pavements and non-accessible toilets or latrines. While planning and design requirements for urban settings could be adapted for rural built environments, due attention needs to be given to local conditions.

Planning and design for the rural areas should take into consideration the options presented by local solutions using locally-available materials. Applied research and experimentation in the use of appropriate technology for the development of barrier-free design for the rural built environment are urgently needed. This is an area for exchange of information among the countries in the ESCAP region.

Goernments, especially local authorities, have a responsibility to improve the understanding of issues concerning barrier-free environments in rural communities. This is particularly so in the case of remote rural areas where there is a lack of non-governmental organization development assistance and the communities have limited access to the mass media. The need for public awareness activities in rural areas is critical in view of the greater difficulty, compared with urban areas, in enforcing access legislation and policy provisions. Actions to improve public awareness of access issues among rural communities include the mobilization of village-level opinion leaders and involving them in dissemination of the relevant messages using folk and traditional media.

8. Slum requirements

In much of the Asian and Pacific region, rapid urbanization has led to a proliferation of slums. The phenomenon is primarily linked with the migration of the rural poor, driven by unemployment, displacement from the land, and the lure of amenities concentrated in metropolitan areas, to towns and cities. The inability of Governments effectively to provide urban infrastructures to meet the needs of this influx compounds the problem.

Slums are characterized by high density habitation, congestion of private and public places, prevalence of insanitary conditions, high risk of exposure to health hazards, disasters such as fires and flooding, as well as drug abuse and crime. The living conditions of slum dwellers in general, and of slum dwellers with disabilities and elderly persons in particular, warrant the special attention of Governments and non-governmental organizations. That attention needs to be directed at integrating barrier-free design concerns as part of the planning and design of provisions for all slum dwellers. Issues concerning equal access to facilities and amenities for persons with disabilities and elderly people living in slums need to be addressed in all slum improvement, rehabilitation and relocation programmes and projects, including schemes for low-cost housing and credit and finance for slum improvement. Goverments should also encourage greater non-governmental organization involvement in augmenting their own efforts.

D. Local authority initiatives (*2)

Many cities in the ESCAP region have not adopted access standards. However, as an interim measure, local authorities can adopt a practical approach to ensure accessibility of certain areas within the city.

Two practical methods for access improvement in an area are described below.

(a)Inclusion of acess requirements in redevelopment projects

In most redevelopment projects, a great deal of time needs to be expended in arbitrating the interests of land owners, developers and local residents. A project usually involves large public infrastructure and facilities. It is, therefore, advisable to include access features in the planning stage of redevelopment projects. The agency responsible for access improvement should work closely with the agencies responsible for the planning of redevelopment projects through consultations, provision of technical expertise concerning accessibility and monitoring of the projects.

(b) Designation of priority areas.

A local authority can designate priority areas to be made accessible within a city. The local authority may, in the case of each selected area:

- Contact various concerned parties, including community groups, self-help organizations of people with disabilities and elderly persons, members of the business community, public agencies and researchers;

- Encourage them to form a committee to promote access in the designated area by:

- Conducting surveys to identify access problems in the designated area;

- Formulating a strategy to solve the problems identified; and

- Presenting possible solutions to business owners and the local administration body.

The above approach emphasizes encouraging the participation of all concerned parties and facilitating face-to-face discussions among them to develop practical solutions. The practical solutions that emerge from a process of mutual understanding, cooperation and compromises among all parties are more likely to be implemented.

This approach can help to improve existing facilities. Full-fledged improvement in existing facilities generally requires large expenditure. In many instances, however, practical improvements can be made with much smaller expenditure through consultations between the parties involved.

E. Special considerations

1. Children with disabilities (*3)

The needs of children with disabilities are often excluded in plans for access. Children with disabilities need stimulation, attention and care just like other children. Like their non-disabled pers, children with disabilities need free access to opportunities to participate in education, recreation and a full range of experiences to be acquired from guided exploration of their environment.

Children with disabilities learn at an early age to cope, physically and psychologically, with their disabilities. They encounter frustration, stress, and sometimes emotional instability in their quest to adapt to their environment. An accessible built environment can play a vital role in minimizing conflict. At the same time, surroundings can be created that are stimulating and suitable for their integration into mainstream activities.

Consideration should, therefore, focus on providing, modifying or arranging the built environment so that non-disabled children may have the opportunity to participate with children with disabilities in as many activities as possible. The following factors must be considered:

- The childs home;

- Transport;

- Outdoor and indoor play;

- Communication;

- School;

- Public areas frequented by children, including libraries, and amusement and shopping areas.

Numerous training devices and materials are available for use with hearing-impaired, deaf, speech-impaired, visually-impaired and blind children.

2. Fire safety (*4)

Efforts to integrate people with disabilities into mainstream society may result in new or increased challenges to raise standards regarding safety in the event of fire. This section describes the important aspects of fire safety to be considered by designers, engineers, fire safety personnel, building managers, as well as non-disabled and disabled facility users.

(a) Fire

Unless there are items in a room which are especially flammable, fire at its initial stage spreads slowly. As the fire gets bigger, toxic gases are given off; these quickly rise to the ceiling and spread under doorways. If there is enough material in the room, the fire will eventually develop very rapidly with flames and smoke engulfing the entire room or building.

If fires are discovered while they are still very small, they can usually be easily extinguished. However, a well-established fire cannot be extinguished by untrained persons and trying to stop such a fire could be extremely dangerous and waste valuable escape time.

(b) Fire-emergency safety

(i) General principles

- Safety is important for everyone;

- Persons with disabilities should be helped to protect themselves; and

- Persons with disabilities should be included in fire safety training.

(ii)Design elements and safety measures

- Fire-safety codes make it essential for buildings to be designed with safety features. Fire-safety design elements are directed towards three objectives:

- Detecting the fire;

- Separating people from the fire either by enabling prompt evacuation of the building, or by providing a refuge area within the building where occupants may safely await rescue;

- Controlling or extinguishing the fire.

In many cases, disabled persons do not require specific design features. However, adequate fire-safety education is a necessary preventive measure. In a fire-emergency situation, non-disabled persons can become handicapped. Everyone is effectively disabled in the case of a fire. Smoke and toxic gases can obscure vision, bells and alarms can impair hearing and create panic and fear, thus limiting the judgemental abilities of everyone.

The ideal situation is for everyone to be as aware and capable of self-preservation as much as possible during an emergency. This often involves modification of the built environment. For example, flashing lights could be activated simultaneously with an audible alarm system to alert persons with hearing impairments. Tactile maps showing alternative escape routes could be installed for persons who are visually impaired. Persons with mobility impairments require little, and sometimes, no assistance from others if areas of refuge have been pre-established and are clearly indicated.

Large public buildings could introduce voluntary registration in the main lobby so that persons with disabilities may easily be located in case of an emergency. Persons with disabilities need to be included in all fire drills.

Increasingly in the ESCAP region fire safety regulations are being strengthened that require high-rise buildings to have special fire-proof lifts for the exclusive use of fire-fighters. However, in the case of those buildings which are frequented by people with mobility impairments, a special agreement should be sought with the fire authority to enable this group of users to have access to the special lifts in emergencies.

(c) Alarm systems

Alarm signals such as flashing lights, vibrating beds or variable velocity fans can alert deaf or deaf and blind residents. Emergency exit lights and directional signals mounted near the floor have been found to be useful in cases where a lot of smoke is present. Pre-recorded messages and on-the-spot broadcasts from a central control centre would be of great benefit.

(d) Raising the alarm

Special devices, e.g., fire alarm boxes, emergency call buttons and lighted panels may be needed by persons who are deaf or blind. Telecommunication devices for deaf persons (TDD) are practical for typing in conversations. A pre-recorded message installed in the telephone would be useful for notifying the fire department.

(e) Refuge

An alternative to immediate evacuation of a building via staircases and/or lifts is the movement of disabled persons to areas of safety within a building. If possible, they could remain there until the fire is controlled and extinguished, or, until rescued by fire-fighters. Some building codes require the provision of a refuge area, usually at the fire-protected stair landing on each floor that can safely hold one or two wheelchairs.

3. Adaptable housing (*5)

"Adaptable housing" means accessible, normal-looking housing which has features that can be adjusted, added or removed to suit the occupants. This applies to disabled, elderly and non-disabled persons. The house could be any shape or size, mass-produced, attractive, and universally usable and affordable.

People with disabilities will have a greater choice of area to live in and visit as adaptable housing becomes more widely available. Both government and private developers will find it less expensive if they mass-produce. Adaptable units could be adjusted or modified without renovation or structural change because basic access features are already part of such units and incorporate reinforcements for installation of handrails/grab bars as needed.

Non-structural adaptations could include changing counter and sink bench heights, removing a cabinet to reveal knee space under kitchen or bathroom sinks and attaching grab bars to walls where necessary. These simple alterations could be made easily by the occupants themselves.

Many elderly persons do not wish to be placed in special housing but recognize that they may need some assistance. Adaptable housing does not look special and its very nature allows many older people to remain in their homes on a more permanent basis.

The increasing demand for adaptable housing creates new opportunities for manufacturers of products for such housing and creates openings for estate agents.

Persons with extensive disabilities often live with non-disabled spouses, other family members or friends who assist when necessary. In an adaptable housing unit, disabled and non-disabled people can live together using the same facilities.

1Source:Design Manual - Access for the Disabled, Building Development Department, Government of Hong Kong, 1984.

2Case-study:Local-level access legislation and policy provisions, presented by the City of Yokohama, Japan, at the Expert Group Meeting on the Promotion of Non-handicapping Environments, 6-10 June 1994, Bangkok.

3Source:The More We Do Together-Adapting the Environment for Children with Disability, Monograph No.31, The Nordic Committee on Disability in cooperation with World Rehabilitation Fund, 1985.

4Source: B. Levin, R. Paulsen, J. Klote. "Fire Safety", Access Information Bulletin, National Centre for a Barrier-Free Environment, Washington, D.C., U.S.A., 1981.

5Source: "Adaptable Housing - A Technical Manual for Implementing Adaptable Dwelling Unit Specifications", Barrier Free Environments, Inc., Raleigh, North Carolina, 1987.

Go back to the Contents

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Promotion of Non-Handicapping Physical Environments for Disabled Persons: Guidelines

- Chapter 2 -

UNITED NATIONS

New York, 1995