Public Awareness Initiatives

A. Introduction

The level of accessibility within a society is a physical manifestation of that societys degree of acceptance of diversity among its members as well as respect for the fundamental rights of citizens to free movement and use of the facilities in its built environment. Ignorance of those rights, combined with insensitivity towards persons with special needs, adversely affect accessibility levels in a society.

Negative attitudes may arise from superstition and fear. Traditional superstitions about persons with disabilities prevail in many Asian and Pacific societies. Some societies believe disability is a result of misconduct in a previous life. Others see disability as punishment for sins committed in the present life. Many individuals harbour a deep-rooted fear that if they are in contact with persons with disabilities, they may also be affected by "evil spirits".

Furthermore, persons with disabilities are commonly perceived to have limited potential. Having a family member with a disability reduces a familys social status. Families may hide such members out of a sense of shame or to protect them from the negative attitudes of ociety. Many people, through lack of knowledge of disability matters and experience of interacting with disabled persons at the personal level, feel uncomfortable in their presence.

Public awareness campaigns are urgently needed to change this situation. The campaigns must address the superstitions and beliefs of each culture to change both perceptions and attitudes toward persons with disabilities.

The United Nations Decade of Disabled Persons, 1983-1992, encouraged the development of self-help organizations of disabled persons. The improvement of public awareness was a major focus of the activities of these organizations. Access to the built environment began to be considered a right rather than a privilege.

The Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabled Persons, 1993-2002, with the aim of full participation and equality, is a critical public awareness opportunity for government departments, NGOs, including self-help organizations of people with disabilities, international organizations and concerned individuals to build on the efforts begun during the United Nations Decade.

B. The initiatives of key agencies and persons

1. Government

The Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in resolution 48/96 at its 48th session on 20 December 1993, state that:

- "States should initiate measures to remove the obstacles to participation in the physical environment. Such measures should be to develop standards and guidelines and to consider enacting legislation to ensure accessibility to various areas in society, such as housing, buildings, public transport services and other means of transportation, streets and other outdoor environments."

In order to implement these recommendations, the following initiatives are suggested:

(a) The formation of a "coordination committee on accessibility" consisting of representatives from government departments and agencies and key NGOs, including organizations of persons with diverse disabilities, elderly persons and associations of architects.

- It is essential that a representative from the budget and finance department be present at all meetings.

- Major issues for action by the committee should include:

- Strengthening of access legislation, particularly its implementation;

- Review of government services and facilities to find out if they are accessible or not;

- Formation of sub-committees (e.g., on transport, public buildings, and housing) to develop action plans and public awareness campaigns;

- Sharing of information and resources among committee members; and

- Regular monitoring of progress and reporting of activities.

- The committee should integrate access promotion into overall development policies and programmes.

(b) In each government department and agency which is on the coordination committee, a person who is sensitive to the needs of persons with disabilities and elderly people should be designated as an Access Officer to serve as an active focal point to expedite the work of the committee.

(c) Awareness of access issues should be improved within each department or agency by:

- Consulting with concerned NGOs, universities and colleges, architects, town planners, builders, civic societies concerned with access, and health and rehabilitation centres;

- Undertaking literature surveys of information materials on access issues and related public awareness campaigns; and

- Organizing information sessions and seminars on access issues for the staff of the department or agency.

(d) Under the leadership of its Access Officer, each government department or agency should develop a long-term access action plan with a time frame that includes:

- Specification of the needs of persons with disabilities and elderly persons in relation to the services and facilities of the respective department or agency;

- Review of existing policies and programmes of that department or agency and identification of those policies and programmes which may discriminate against persons with disabilities or elderly people.

- Establishment of department/agency priorities in the improvement of accessibility, e.g., through review of buildings, services and facilities, use of new technologies, publications policy and information formats, from the perspective of persons with disabilities and elderly people;

- Identification of staff training needs concerning access issues and mobilization of resources to meet those needs;

- Formulation of guidelines for inter-agency and inter-organizational cooperation that focus on supporting the improvement of accessibility;

- Introduction of support of access concerns as a criterion for funding NGOs;

- Initiation of pilot projects on access promotion and dissemination of outcomes; and

- Barrier-free design as a feature of all new government buildings and renovations.

(e) Promote within the Government positive attitudes and good practice concerning the integration of persons with disabilities and elderly persons, to set an example to the rest of society.

2. Self-help organizations of people with disabilities

Self-help organizations of people with disabilities, by making available their experiences as users and giving high visibility to the issue, can play a useful role to improve accessibility. The Standard Rules on the Equaization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities state that:

- "Organizations of persons with disabilities should be consulted when standards and norms for accessibility are being developed. They should also be involved locally from the initial planning stage when public construction projects are being designed, thus ensuring maximum accessibility."

The organizations should take the initiative to form access groups at the community level, focusing on:

- Advocacy;

- Consultation and cooperation;

- Monitoring.

3. The role of elderly persons (*6)

The active participation of elderly persons is critical to developing successful public awareness-raising campaigns on access promotion. The demographic trends demand that serious attention be accorded to addressing the needs of rapidly ageing societies in the ESCAP region. Furthermore, it is estimated that, out of the total number of persons with disabilities, at least half are elderly people.

Traditional Asian and Pacific social values emphasize respect for elderly people. However, in the process of rapid social and economic change, those values are being increasingly challenged. Barrier-free environments would enable many more elderly people who are frail or disabled to continue to participate in family and community life.

Organizations for and of elderly persons are usually well established and can facilitate the creation of barrier-free environments. These organizations often include articulate and educated elderly persons who have the knowledge and skills to bring about change.

4. Local-level access groups

A local-level access group should be composed of persons with diverse disabilities, elderly persons, architects, engineers, planners, building control officers, lawyers, environmental and health officers, local authorities and local business groups and trade unions.

(a) Start-up steps

The following steps may be followed in order to start a local-level access group:

- Identify potential members from among community members with an interest in access issues, concerned government officials, and community leaders.

- Call a meeting of potential members to discuss the formation of a local-level access group.

- Sensitize the group to access issues by organizing:

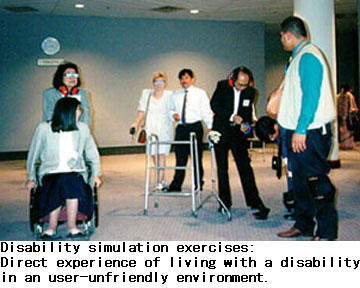

- Training workshops, including disability simulation exercises;

- Group work to survey the accessibility of local areas and identify possible solutions;

- The collection of information and materials on local area approaches to access promotion.

- Develop communication and negotiation skills on access issues.

- Identify priority issues and develop a media strategy.

- Develop a plan for group action with targets such as the following:

- Selected parts of the built environment in a locality to be made accessible within a specified time-frame, e.g., 50 per cent of primary schools, playgrounds and libraries to be made accessible to children with disabilities within a three-year period;

- Installation of ramps and cutting of kerbs on every pathway and road ina selected area within a specified period;

- Amount of funding to be generated for achieving access targets.

- Monitor and evaluate regularly the progress of the group action plan.

(b) Activities

Among the activities which a local-level access group may pursue are:

- Consultations with the local authority on access issues. A successful local-level access group cooperates actively with its local authority officials. It assists in monitoring improvements to the local environment. It reports on hazards, places where new access features or maintenance work on existing ones may be needed, and violations of access standards and legislation.

- Campaigns for improved access, particularly to existing buildings and public transport. Awareness-raising among the general public must be undertaken on a continuous basis. A local-level access group should use publicity as a tool to encourage the emulation of examples of good practice and to generate fear of negative press coverage. Group members should be trained to address civic organizations, schools and business associations on local access issues. The cultural bases of prevailing attitudes and patterns of behaviour concerning persons with disabilities and elderly persons in the community may be examined. This will assist in developing appropriate local approaches to reducing social and physical barriers.

- Advisory services to property developers on access matters. The local-level access group should find ways to encourage the incorporation of access features in the development of real estate in its locality.

- Information exchange with other bodies working on access.

5. Associations of professionals

Architects, engineers, urban planners, landscape designers, transport planners and lawyers together determine the accessibility of the built environment.

Associations of professionals composed of members of these groups need to understand their responsibility for creating barrier-free environments that benefit all users.

The following initiatives are suggested for associations of professionals:

- Adopt a team-building or partnership approach in working with persons with disabilities and elderly people to improve the accessibility of the built environment.

- Organize joint outings for association members and user groups to highlight both good and bad examples of accessibility.

- Prepare audio-visual materials on inaccessible environments and examples of barrier-free designs for use in presentations.

- Ensure members have information on the criteria for access, templates of access design, as well as access solutions and guidelines.

- Facilitate direct exchanges between members and professionals with work experience on access promotion.

- Strengthen international networking on access issues among professional associations, including contacts between those in developed and developing countries.

- Actively encourage barrier-free design through the provision of fellowships, study opportunities and on-site technical exchanges between members and students.

- Generate discussion in professional journals, newsletters and conferences on the development of designs for accessible built environments in a variety of social, economic and political contexts.

- Provide training programmes for members on designing and building for accessibility.

- Organize competitions on access design, awards and public recognition of significant contributions to access promotion.

- Provide training opportunities for organizations of people with disabilities and elderly persons to strengthen their technical expertise on accessibility issues.

- Undertake, in collaboration with members, persons with disabilities and elderly persons, demonstration projects to illustrate the advantages of barrier-free design.

6. Higher education institutions

Many architects, engineers, building designers and town planners lack a conceptual understanding of access issues and technical knowledge of how access features should be incorporated into the built environment.

Education institutions directly influence the development of a sense of social responsibility among future professionals. There is an urgent need for these institutions in the ESCAP region to introduce into theircurricula conceptual understanding and practical knowledge of access issues.

The following initiatives are suggested for education institutions:

- Organize diverse awareness activities to encourage interest in access issues.

- Provide opportunities for students to meet people with a range of disabilities and to hear and discuss first-hand experiences of mobility problems in the built environment.

- Integrate students with disabilities into classes and extra-curricula activities, not least by making buildings accessible to them.

- Include staff (full or part time) with disabilities in regular teaching programmes.

- Encourage design projects for students which involve accessibility issues, and invite people with disabilities to participate both in briefings and feedback activities.

- Ensure that all relevant codes and associated design issues on accessibility are included in the teaching curriculum, and are taught in such a way as to make them meaningful to the developing mind.

- Include disability simulation exercises as an integral part of all courses concerned with the design of the built environment.

- Encourage postgraduate study and research into topics related to accessibility by seeking sponsorship or providing grants.

- Organize competitions or "live projects" on barrier-free design topics to encourage students interest in accessible environments.

- Develop resource material, including audio-visual material and computer programmes, on access issues.

- Encourage student unions or councils to address issues concerning those barriers faced by young persons with disabilities to education and to full participation in all aspects of life taken for granted by people without disabilities.

C. Promotion of public awareness: principles and strategies

1.Printed materials and alternative formats

It is imperative that access issues be promoted in ways that the public can easily relate to and understand. Printed materials should be tailored to suit specific groups and be written in concise, easy-to-read language. Large print publications, Braille publications and audio tapes should be made easily available to all who need them. This applies to publications from Governments, NGOs, and the private sector.

The following initiatives are suggested for accessible print materials:

- All print materials for public consumption, e.g., pamphlets, brochures, documents, letterhead paper, business cards and promotional leaflets, should be clear, concise and be written in simple language.

- Print materials should be easy to read. They should have good colour contrast, suitable print size and font. Font size 14 points is recommended and fancy fonts should be avoided. Clear and simple diagrams should be used.

- Materials should also be available in Braille and audio formats as well as on computer diskettes and in large print. Materials in video formats should include subtitles.

2. Use of correct terminology (*7)

Language can be used to shape ideas, perceptions and attitudes. Words in popular use mirror prevailing attitudes in a society. Those attitudes are often the most difficult barriers that persons with disabilities and elderly persons face. Positive attitudes can be shaped through careful presentation of information about them.

The following guidelines are suggested for government departments, the mass media and organizations which promote access issues:

- Describe the person, not the disability.

- Refer to an individuals disability only when it is relevant.

- Avoid images designed to evoke pity or guilt.

The following are examples of negative and positive use of words and expressions in the English language. The same principles may be applied in the case of other languages.

| Instead of... | Use... |

| The disabled, the handicapped, the crippled | Persons or people with disabilities |

| Crippled by, afflicted with, suffering from, victim of, deformed | Person who has or person with (name of disability) |

| Lame | Person who is mobility-impaired or person with a mobility impairment |

| Confined, bound, restricted to or dependent on a wheelchair | Person who uses a wheelchair or wheelchair user |

| Deaf and dumb, deaf mute | Deaf person, person who is hard of hearing, hearing-impaired person or person with a speech impairment |

| The retarded, mentally retarded or mentally subnormal | Person with an intellectual disability or person with a developmental disability |

| Spastic (as a noun) | Person with cerebral palsy |

| Mental patient, the mentally ill, mental or insane | Person with mental illness (specify illness if known, e.g., schizophrenia or depression) |

| The blind or the visually impaired (as a collective noun) | Persons who are visually impaired or blind, persons with visual impairment, or blind persons |

3. The mass media

Effective media involvement is critical to the success of public awareness-raising. A good public relations plan is essential. The following are suggestions for effective involvement of the mass media in access promotion:

- Develop a media action plan with a time-frame. The plan can include collaboration with the mass media in the organization of workshops on the role of the media in access promotion.

- Inform the media about events organized by local-level access groups and access coordination committees. Visit media managers, newspaper editors and television directors to underline the need for improvement of the quality of coverage of access issues.

- Disseminate a guide on media communication concerning people with disabilities. The guide should include appropriate terminology for describing persons with disabilities.

- Provide media personnel with:

- Information on the barriers encountered by persons with disabilities and elderly persons. Include information on persons with epilepsy, cerebral palsy, schizophrenia, deafness, developmental disabilities and physical disabilities;

- Examples of the successful removal of barriers to the built environment (ramps for wheelchair users, audible crossing signals for blind persons and modified public telephones for persons with a hearing impairment);

- Human interest stories on and profiles of persons with disabilities. The focus of these should be on abilities and human dignity, and not on disabilities. These should be in a form that can easily be adapted by journalists or used by them to conduct interviews with the persons concerned.

- Articles and feature items that question local superstitions and beliefs concerning disability, as a step towards improving attitudes towards persons with disabilities.

4.Forming a speakers bureau in the community (*8)

By visiting schools, civic clubs and local businesses and offices, organizations of people with disabilities and elderly persons can disseminate information on disabilities and barrier-free environments. The following suggestions may be pursued:

- Find out if there is a speakers bureau representing organizations of people with disabilities in the community. If there is none, ask local organizations of persons with disabilities and elderly persons to propose members who have sufficient knowledge of access issues and who would be willing to speak on those issues. Compile a list of speakers from a variety of disability groups.

- Appoint a person to coordinate the speakers bureau.

- Compile a presentation package, including slides, video clips, brochures and handbooks, for the speakers use.

- Arrange for potential speakers to receive training in public speaking and briefing meetings.

- Prepare handouts and information kits on access issues.

- Discuss questions that may arise and appropriate answers.

- Contact civic clubs, schools, womens groups, business associations and other groups, to inform them of the availability of speakers.

5.Approach to the rural community

A considerable gap in the level of public awareness towards disability exists between the urban and rural areas. In the preparation of public awareness programmes, consideration should be given to the diverse requirements of urban and rural communities. In the case of rural communities, the following strategies should be considered:

- Identification of opinion leaders at the village level such as administrative heads, religious leaders, primary school teachers and community workers, to sensitize them to the needs of persons with disabilities and elderly persons;

- Use of folk or traditional media (e.g., puppetry and shadow play in local languages and dialects) as campaign materials for the dissemination of messages on themes stressing the need for barrier-free environments in the rural areas, to dispel prevailing myths and superstitions about disability as punishment for sins committed, and encourage villagers to accept measures for the prevention of the causes of disability and the rehabilitation of persons with disabilities.

6.Launching a National Access Awareness Campaign

National Access Awareness Campaigns are aimed at encouraging government agencies, NGOs, private sector bodies and individuals to cooperate on access improvement.

The goal of a National Access Awareness Campaign is to provide an opportunity for individuals and communities to improve the quality of life of all citizens by identifying and removing the barriers that restrict access for some groups.

After setting up a National Access Awareness Campaign, activities must be sustained as part of a growing process (see Annex VI: National Access Awareness Week Campaign).

People with campaign experience and knowledge of access issues as faced by persons with disabilities and elderly people must be integrated into the structure of a campaign at all levels. Clear and realistic targets must be set at the start of a campaign, if full integration is to occur.

The national executive committee of a campaign should provide policy guidance and conduct public relations affairs. This committee should oversee all aspects of the access campaign and be the direct point of contact for sponsors and participants. The chairperson should preferably be a person with a disability who has technical competence on addressing access issues. The committee needs to consist of representatives from government agencies, NGOs, including organizations of persons with disabilities and elderly persons and the private sector.

National Access Awareness Weeks can be organized as part of the campaign process to give new impetus to long-term endeavours. Progress should be reviewed and new goals planned yearly.

D. Training on access issues

Continuous training is of critical importance to the long-term success of access promotion. Professionals who are introduced to access issues at college or university should attend periodic refresher courses to update them on current developments. New legislation and standards can be incorporated into these sessions. It is equally important for building maintenance staff and media personnel to attend these training courses.

Persons with disabilities must participate in the training courses. They can give first-hand accounts of their experiences and suggest improvements. Access training is always far more effective if the trainees can discuss issues with those who are directly affected by them.

Disability simulation exercises (*9) can assist in improving understanding among non-disabled persons of how it feels to live with a disability in an insensitive environment which is not user-friendly. The length of time spent on a simulation exercise can vary. Overnight exercises can be especially beneficial for experiencing first hand a wide range of social and physical barriers encountered by persons with disabilities. Experiences can be discussed in detail the following morning. The exercise should be conducted or supervised by an experienced instructor.

When used during a public awareness event, simulation exercises can attract a great deal of media attention. It is especially bneficial if popular public figures take part in such events.

E. Regional cooperation

Considerable imbalance exists in the degree of accessibility of the built environment in different parts of the ESCAP region and between the urban and rural areas within countries. Lack of information and awareness, especially in ESCAP developing countries, contributes to this imbalance. The present guidelines on the promotion of barrier-free environments have been developed as a tool to improve overall accessibility in the region. Close regional cooperation would greatly facilitate their implementation.

The following is a list of some regional organizations in the ESCAP region which could network and cooperate on access issues:

- Regional NGO Network for the Promotion of the Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabled Persons

Secretariat: c/o Japanese Society for Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons, 1-22-1, Toyama, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162, Japan (Tel: 81-3-5273-0601, Fax: 81-3-5273-1523) - South Asian Network of Self-help Organizations of People with Disabilities

c/o Social Assistance and Rehabilitation for Physically Vulnerable, 1/2, Kazi Nazrul Islam Road, Mohammadpur, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh (Tel: 880 2 327611, Fax: 880 2 819774) and National Federation of the Blind 2322, Laxmi Naraen Street, Pahar Ganji. New Delhi-55, India (Tel: 91-11-521885; Fax: 91-11-7522410) - Disabled Peoples International, Asia and the Pacific Regional Council

Regional Programme Development Office, 20 Don Vincente Street, Don Antonio Heights, Commonwealth Avenue, Quezon City 1121, the Philippines (Tel/fax: 63 2 931 0539) - Rehabilitation International, Office of the Regional Committee for Asia and the Pacific

c/o The Hong Kong Council of Social Service, Duke of Windsor Social Service Building, 15 Hennessy Road, 12/F Hong Kong (Tel: 864-2929, Fax: 865-4916) - World Federation of the Deaf (Regional Secretariat in Asia and Pacific)

c/o S.K. Building, 130 Yamabuki-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, JAPAN (Tel: 81-3-3268-8847, Fax: 81-3-3267-3445) - World Blind Union

Asian Blind Union: c/o President, V-E, 20/13, Mehar Manzil, Nazimabad #5, Karachi 74600, Pakistan (Tel: 6681897, 6612391, Fax: 6681898, 7729935)

East Asia: c/o Hong Kong Association of the Blind, 2 Flint Road, Kowloon Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong, (Tel: 852-3384231, Fax: 852-3387850)

The Pacific: c/o Royal New Zealand Foundation for the Blind, 39 George St., Newmarket, Private Bag 99941, Newmarket, Auckland, New Zealand (Tel: 0-9-309 6333, Tel: Private: 0-9-523 1332, Fax: 0-9-366 0099) - HelpAge International, Asia Training Centre on Ageing

c/o Faculty of Nursing, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand (Tel: 66-53-221-294 and 221-122 Ext. 5045, Fax: 66-53-221-294 and 217-145) - Regional Network of Local Authorities for the Management of Human Settlements (CITYNET)

Secretariat: 5F, International Organizations Centre, Pacifico-Yokohama, 1-1-1 Minato Mirai, Nishi-ku, Yokohama 220, Japan (Tel: 81-45-223-2161, Fax: 81-45-223-2162) - Network of Human Settlements Training, Research and Information Institutes in Asia and the Pacific (TRISHNET)

(Contact: Human Settlements Section, Rural and Urban Development Division, ESCAP, UN Building, Rajdamnern Avenue, Bangkok, 10200, Thailand (Tel: 662-288-1234, Fax: 662-288-1000) - Asia Pacific 2000, Urban Management Programme

Regional Coordinator, c/o United Nations Development Programme, Wisma UN Block C, Komplek Pejabat Damansara, Jalan Dungun, Damansara Heights, 50490 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Tel: 2559122-2559133, Fax: 2552870) - International Union of Local Authorities (IULA)

c/o Secretary-General, Asian and Pacific Section, 8, Pahlawan Kalibata Street, Selatan, Jakarta, 12740, Indonesia (Tel: 62-021-7982659, Fax: 62-021-354447) - Architects Regional Council Asia (ARCASIA)

c/o 2nd Floor Prudential Bank Building, Ortigas Avenue, Greenhills, San Juan, Metro Manila, Philippines 1503 (Tel: (632) 7211661-62, Fax: (632) 7212518)

6 Contributed by Finlay Craig, Regional Representative, Asia, HelpAge International, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

7 This section is based on A Way with Words: Guidelines and Appropriate Terminology for the Portrayal of Persons with Disabilities, Status of Disabled Persons Secretariat, Department of the Secretary of State of Canada, Ottawa, 1991, and Words with Dignity,Active Living Alliance for Canadians with a Disability, Ontario, Canada.

8 Based on Independence, Thats Living!: Organisation Handbook, National Access Awareness Week: Integrating Disabled Persons, June 4-10, 1989, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, p. 19.

9 The disability simulation exercise as described here is based on that developed by the Asia Training Centre on Ageing, HelpAge International, Chiang Mai, Thailand (see Annex VII: "Disability Simulation Exercise" for details).

Go back to the Contents

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Promotion of Non-Handicapping Physical Environments for Disabled Persons: Guidelines

- Chapter 3 -

UNITED NATIONS

New York, 1995