Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For , By and With Disabled Persons

INTRODUCTION

Disabled Persons as Leaders in the Problem-Solving Process

This is a book of true stories about people's creative search for solutions. Written for disabled persons and their relatives, friends, and helpers, its purpose is to share exciting, useful ideas, and to spark the reader's imagination: to stimulate a spirit of adventure!

This book differs from most manuals on disability aids and equipment in 4 basic ways:

1. We make an effort to put the person and the process before the product. The 50 chapters cover a wide selection of disability aids that are relatively easy to make at home or in a village. But in presenting each innovation, emphasis is put less on the end-product (however important) than on the cooperative process of discovery.

In this approach, the disabled person (and/or family members) often takes the lead, working as a partner and equal with service providers, technicians, or local crafts-persons. With this sort of partnership approach, results tend to be more enabling than when assistive equipment is unilaterally prescribed or designed.

2. Our goal is not replication, but rather adaptability and shared creativity. True, most aids shown here can be easily replicated (copied exactly) at low cost at home or in a village workshop. However, placing strong emphasis on replication can be counter-productive . . . especially in the field of rehabilitation where the needs, possibilities and dreams of each disabled person are different. Too often, the routine construction of standardized designs contributes to a habit of trying to adapt the disabled person to the assistive device, rather than trying to adapt the device to the disabled person.

Therefore:

Our objective is not to catalogue a set of aids and equipment to be copied,

but to share an EMPOWERING PROBLEM-SOLVING APPROACH.

3. In most examples in this book, we start by looking at an individual disabled person. Placing that individual as central to the problem-solving process, we explore her or his unique combination of wishes and needs. Then we describe the cooperative, trial-and-error methods used in designing and testing possible solutions. The problem-solving is ongoing and open-ended. It may include anything from learning new skills or modifying the environment, to the invention or adaptation (or elimination) of an assistive device.

4.Most of the rehabilitation workers and technicians responsible for the innovations in this book are themselves disabled. Because they too have a disability, they are more inclined to work with a disabled "client" as a partner and equal in the problem-solving adventure. Also, being disabled, they often have insights (an insider's view) leading to new approaches that help enable the disabled individual with whom they work.

PROJIMO

Most of the innovations explored on these pages were created in PROJIMO:Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico. This small community-oriented program is based in Ajoya, a village of 1000 inhabitants in the mountains of Western Mexico. The author of this book - himself disabled (see Chapter 11) - has worded as a facilitator and advisor to the program since it began in 1981. On the next page we give a brief account of how PROJIMO differs from similar community programs. For more information on the program we suggest you look at Disabled Village Children, a handbook which grew out of PROJIMO (see page 343). Or write to us at HealthWrights.

How PROJIMO Differs from Many CBR Programs

PROJIMO - the program in Mexico run by disabled villagers where most of the innovations in this book come from - differs from many Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) programs in that:

- PROJIMO was started by, and is organized and run by disabled villagers.

- It grew out of and is linked to a villager-run primary health care program.

- The program includes a village-based rehabilitation center where disabled persons and family members can learn skills, take part in the creation of assistive equipment, and help and learn from each other.

- Services are provided, and assistive equipment is made by disabled persons who learn their skills mainly through apprenticeship, from one another and from volunteer rehabilitation professionals and skilled technicians. (These "experts" are asked to devote their short visits to teaching skills rather than providing services.)

- The quality and thought that goes into this work has developed beyond what you find in many community programs - because the PROJIMO workers have had years of challenging interchange with exceptional leaders in different fields of disability. Indeed, aids and equipment designed for and with disabled individuals sometimes meet their specific needs more effectively than those provided by large urban rehabilitation centers, and at a much lower cost.

PROJIMO'S Need for Creative Problem Solving

Since its beginning, PROJIMO has been fairly innovative, not only technically but in its overall organization and structure. The disabled workers take pride in running their program on their own terms and in experimenting with participatory models of decision-making, management, and funding. In each of these areas they have had striking successes and failures. The program has evolved through a series of productive crises, the worst of which have threatened to destroy the program (see below). But each crisis somehow forces the team to re-evaluate its methods and to experiment with alternative approaches, which at times prove to be major steps forward.

PROJIMO began with the intention of serving physically disabled children. But soon children (and adults) with other disabilities, including developmental delay and multiple impairments, were brought for help. So the team has sought to expand its capabilities to meet these needs. But it is still most skilled and innovative with physical disability, an imbalance reflected in this book.

The Disabling Effect of Growing Poverty and Violence

Ironically, the biggest challenge to PROJIMO's survival has come about with the increase in spinal-cord injured teenagers and young adults. In the last decade, hundreds of these youths - most disabled by bullet wounds - have found their way to PROJIMO from all over Mexico. Their numbers reflect the mushrooming sub-culture of violence. As in much of the Third World, poverty, landlessness, and unemployment have grown with Mexico's structural adjustment to "free trade" and the inequities of the global economy. The widening gap between rich and poor leads to an increase in crime, alcoholism, drug trafficking, street-children, armed gangs, and wide-spread social unrest. The state reacts with ever harsher repression, corruption, police brutality, and institutionalized violence. All this has led to a substantial increase in disability, especially among young men.

New Challenges for Hard Times. The youths arriving from this devastating sub-culture of violence are often both physically and psycho-socially disabled. Their habits with alcohol, drugs, and violence are deeply ingrained. PROJIMO has tried to set rules and has initiated peer counseling, but with mixed or delayed results. Meanwhile, the program's reputation has suffered; parents are reluctant to bring their young children. So PROJIMO has increasingly become a program catering to disabled teens and young adults (especially those with spinal-cord injury). In the long run this upsetting change may be for the good. Many children who used to come to PROJIMO now go to emerging programs - some started by PROJIMO's disabled "graduates" - conveniently located in several states of Mexico. But PROJIMO is still the only one of these programs that attends physically and psycho-socially disabled street youth.

From Violence to Caring

Not all of the disabled youths coming to PROJIMO with a history of drugs and violence turn out well. But some go through heart-warming transformations. Perhaps because of their own difficult childhood, their hearts often go out to those disabled children who are least pleasing and most vulnerable. The following true story illustrates this.

QUIQUE AND JOSÉ. Not long ago, a 7-year-old brain-injured boy named José was temporarily abandoned by his family at PROJIMO. Limited by extensive physical and mental handicap, José was fretful and unresponsive. He had no urine or bowel control. Repeated attempts to toilet train him failed. Whenever his bowels moved (too often!) he smeared his feces (shit) over his body, face and hair. Even PROJIMO's coordinators, Mari and Conchita, who are themselves disabled and usually very loving with disabled children, were at the end of their wits and patience with José.

Then an amazing thing happened: a friendship developed between José and Quique. Quique, a young man paralyzed from the neck down (quadriplegic), had an angry, belligerent temper. Repeatedly he was expelled from PROJIMO for drug dealing, drunkenness, and trouble-making. One day Quique was lying on his gurney under a mango tree when, unexpectedly, he and littie José began to communicate. José could not speak, but somehow Quique caught his interest. When Quique talked to him - not as a misfit but as a friend - the boy began to grunt and eventually smile. With effort José rolled his wheelchair next to Quique and slipped his filthy little fingers into Quique's gaunt, paralyzed hand. From that moment the two were inseparable.

Quique assumed a protective responsibility for José. He demanded that the boy be bathed when he dirtied himself, and gently encouraged him to wash his own hands and feed himself. José began to show improvement in many ways, and smeared himself with his feces less often. Both he and Quique seemed happier.

Quique's strangely insightful, caring response to José was not unusual. Time and again, disabled youth who arrive socially scarred and violent have become among the most considerate care providers for those in greatest need.

Some of the most lovingly conceived innovations in this book were created by young disabled persons

who emerged from the sub-culture of drug-trafficking and violence.

PROJIMO's Involvement With Innovative Participatory Technology

Toward the end of 1990, PROJIMO received a three year grant for Innovative Research from the Thrasher Research Fund in North America. Many of the innovations in this book were developed during this grant period, while some were developed before or after. In addition, to emphasize important points, a few innovations are included from other regions, ranging from India to Bangladesh and from Zimbabwe to Belize and Brazil.

|

Ralf Hotchkiss, a wheelchair-riding engineer from California, with Concepción in a chair made in a wheelchair-making workshop at PROJIMO. Ralf has helped to design many great innovations together with disabled Third World wheelchair builders (see Chapter 30). |

Many of the innovations presented in this book have been developed by the PROJIMO team together with 3 sorts of participants:

- Disabled persons and family members have been central to the problem solving process. Designs have been created to meet the expressed needs of disabled individuals and have been adapted, on their terms, to local social and environmental conditions, economic limitations, and locally available resources.

- Participants from community rehabilitation and disability programs in Mexico and Central America have taken part in designing and building innovative aids during short workshops and "educational exchanges." Most of the participants were themselves disabled. Having a disability was considered a valued qualification, both for learners and facilitators. In this way, the methodology and "mystique" of the innovative approach has been widely shared.

- Volunteers from Europe, Latin America, the USA and elsewhere, many of them innovators and experts in their respective fields, took part in most of these short workshops and mini-courses. They included prosthetists (leg makers), orthotists (brace makers), seating specialists, wheelchair designers, physical and occupational therapists, and instructors in early development and special education. Many (but not all) of these visiting specialists were also disabled. All came with an understanding that their role was to teach rather than to provide services, and to work as partners and equals with local rehabilitation workers (mostly disabled villagers) and with disabled clients and their families.

As a result of this unique combination of disabled community rehabilitation workers and disabled clients working together with visiting apprentices and outside specialists, many of the innovations described in this book have been created through a cooperative, equalizing process. As readers will notice, a lot of these aids and devices combine scientific sophistication and grassroots simplicity.

This sort of collective problem-solving process teaches us a lot. Above all, we learn to respect one another's contrasting insights and skills.

DISABLED PERSONS MAKE MAJOR BREAKTHROUGHS IN DESIGNS

|

Louis Braille invented this dot alphabet at age 14. The dots are pressed into a thick paper from the opposite side with a pointed tool called a 'stylus'. |

A lot of professionals are unwilling to include disabled persons as partners in designing solutions to their needs, and often disabled persons are reluctant to assume such responsibility. Nevertheless:

Many major breakthroughs in rehabilitation technology

have been designed and created by disabled people themselves.

For blind people, of course, the most famous breakthrough was a brilliantly simple form of reading tiny raised dots with the finger-tips. This was invented by a blind French boy, Louis Braille. Rather than supporting his innovation, his teachers in the School for the Blind punished Louis and his classmates for experimenting with his new system. So they used it in secret! For those in positions of authority, it is often difficult when persons under their control take the lead. In every sense the invention of Braille was revolutionary - and for blind people it was liberating.

In recent years many of the most outstanding designs of communications aids, wheelchairs, and limbs have been developed by wheelchair riders, amputees, and other disabled persons. Dissatisfied with the equipment available to them, these persons invented something better.

A major breakthrough in artificial limbs is the flex foot, which was invented by an amputee. When the person walks, the flexible foot-piece acts like a spring, simulating the push-off action of a normal foot. This makes walking easier, smoother, faster, and it takes less energy.

|

The lower leg and foot are made of a curved thin strip of carbon fiber, a strong, flexible space-age material.

|

The foot-piece bends more when the person steps on it, in effect loading the spring.

|

At the end of the step, the foot-piece gives a downward and forward push, propelling the person forward.

|

John Fago, a professional photographer who has an artificial leg, studied limb-making after visiting PROJIMO and then started making his own leg. Concerned more with function than appearance, he is designing a flex leg shaped like an upside-down question mark: ¿

The entire leg acts like a spring, giving the user a powerful forward thrust. Also - with the help of a man who designs bamboo fishing poles - John is experimenting with making a flex foot out of laminated bamboo, instead of costly carbon fiber. His goal is to help poor communities to make flex-feet with local resources at low cost.

TECHNICAL AIDS AND EQUIPMENT ARE IMPORTANT

One reason for writing this book is that in many programs for disabled people in poor countries and communities, too little attention is given to technical aids and assistive equipment. The current trend is to down-play the technological side of rehabilitation. This comes both from disabled people's organizations and from planners of community based rehabilitation (CBR) programs:

- Disabled activists and organizations in the North are passionately concerned with disability rights. In their struggle to achieve a Society for All, they focus on social issues such as accessibility, equal opportunity for education, jobs, etc. They are less worried about technical aids. After all, most members of leading disabled people's organizations, especially in the North - and of Disabled Person's International, even in the South - belong to the middle class. They already have the essential personal aids they need. So their top priority is the struggle for their social rights. They have tended to project their own priorities onto the poor disabled people of the Third World, whose lack of assistive equipment (braces, wheelchairs, etc.) may be their biggest limitation.

- The official World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for CBR have also (in the past more than at present) under-emphasized the importance of technical aids. Some CBR advocates assert that devoting attention to assistive equipment is a return to the "medical model" of rehabilitation, which they criticize (in large part, correctly) as being top-down, professional-dominated, costly, disempowering, and impractical. Technical information on assistive equipment in the WHO manual tends to be quite limited and superficial. Much stronger emphasis is placed on the social side of rehabilitation: schooling, skills training, job placement, community participation, etc.

It is true that social considerations are extremely important, and are still inadequately addressed in most urban "rehabilitation palaces." But for millions of poor disabled persons, the lack of low-cost, appropriate mobility aids and assistive equipment is a major barrier to social integration - including schooling, jobs, and self-reliant living.

For example, wheelchair accessibility is a big concern for those who have wheelchairs. But 95 percent of people who need a wheelchair don't have one. Similarly, many who need leg braces or artificial limbs to subsist in difficult circumstances don't have them. Or they are given devices of such poor quality that they are of questionable benefit.

Appropriate aids can make a huge difference in terms of self-determination, social integration, and survival. But to create equipment that is appropriate, we need to work closely with the disabled persons concerned. We must consider the disabled person's unique combination of skills, wishes, impairments, opportunities, income, and motivation, as well as personal and environmental possibilities and constraints (within home and community). Designs may differ according to local resources, cost, accessibility, means of transportation to school or work, and the support system within the family and community.

ACHIEVING A SOCIETY FOR ALL: NEED FOR AN INTEGRATED APPROACH

To achieve a society in which disabled people can participate fully, 3 things are needed:

- Personal rehabilitation and assistive equipment for improved function and mobility.

- Accessibility in terms of the physical environment, transportation, etc.

- An accepting, welcoming attitude of the general population, with readiness to provide equal opportunities. Supportive legislation can help open doorways to social rights.

Fulfilling only one or two of these requirements is not enough: all three must be achieved. The need for this integrated three-armed approach is pictured on the next page.

A 'SOCIETY FOR ALL'

can only be achieved through

AN INTEGRATED APPROACH

POVERTY AND DISABILITY: SURVIVAL COMES FIRST

Persons trained in the field of rehabilitation, as in other fields, tend to see people's needs in terms of their specialty. A rehabilitation worker, on seeing a disabled child in an urban slum, may think first of the child's disability-related needs. The worker may want to foster an "integrated approach," including assistive devices, access to schooling, and social involvement. But it is essential to remember that for that child and millions of other children, their basic health and survival needs come first.

Most important for any child, whether disabled or not, is meeting her basic needs for food, shelter, and essential health care.

Too often, rehabilitation planners overlook or give too little attention to the economic limitations of the family. As a result, sometimes hundreds of dollars are spent on an orthopedic brace, hearing aid, or on special schooling - only to see the child die from untreated infection ... or from hunger.

Quite rightly, many community rehabilitation initiatives are putting more time and energy into helping disabled persons and their families find ways to produce food or add to their income. For example, some programs give a goat, rabbits, or chickens to a disabled child, and help her learn to care for and breed them.

Hard and Soft Technologies

Poverty and disability together put people, especially children, at double risk. Both must be dealt with. People who are disadvantaged for whatever reasons need to join in the struggle for equal rights and full participation in a fairer, more caring society.

Therefore, when we think of "rehabilitation technology," it is important to consider not just the hard technology of aids and

equipment, but also the soft technology of ideas and action that can help disabled persons to survive, meet their needs, and be more self-determined.

The last two Parts of this book look at innovative soft technologies. These include activities and methods whereby disabled people can defend their rights, integrate into society, and learn skills to earn a living and keep the wolf from their door.

Adapting to Extreme Poverty in an African Squatter SettlementOne of the most innovative community based rehabilitation (CBR) programs that I (the author) have visited is in a huge shanty town called Matari Valley, in Nairobi, Kenya. This settlement was formed in colonial times by young women from rural areas who worked in the city as house girls and mistresses for white masters. When the girls got pregnant, they were thrown onto the streets and settled in Matari Valley. Today hundreds of thousands of single mothers survive there by brewing illegal liquor, selling their bodies, begging, and picking through garbage. A large number of children are disabled. Many mothers leave their disabled child shut up all day, sweltering in tar-paper shacks. The mothers do this, not by choice, but in their efforts to earn enough to feed their children at least one meal a day. A CBR worker named Penina, who went to Matari Valley several years ago found that the first concern of mothers with disabled children was not "rehabilitation," assistive equipment, or schooling. Their worries had to do with food, sickness, and survival.

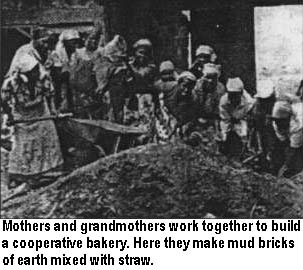

So Penina modified her rehabilitation plans. She put the survival and basic needs of the children first. She began by looking for ways to help mothers earn a little income in their homes, so that they could spend more time with their children. At times this meant giving mothers small loans to start selling lamp oil or charcoal. She helped groups of mothers form child-care cooperatives, so that they could take turns caring for one another's children while the rest sought outside work. She then helped mothers form sewing, chicken-raising and other small work cooperatives to produce an income and have shared child-care where they work. Once the mothers were earning a bit more income, they could feed their children better and spend more time with them. So Penina began to introduce early stimulation and developmental activities into the child-care groups. From among those mothers who showed the most interest, love, and natural ability, she trained several to help as facilitators, teachers, and neighborhood rehabilitation assistants. As day-to-day survival became less of a struggle, the mothers were able to devote more time to assisting their disabled children. Penina began to teach the mothers exercises and activities they could do in the home to help their children learn skills and become more independent. As much as was possible given the limited resources, she helped them to access the aids and services that they needed. As the mothers began to see signs of improvements in their children, they confidence grew, both in themselves and in the potential of their children.

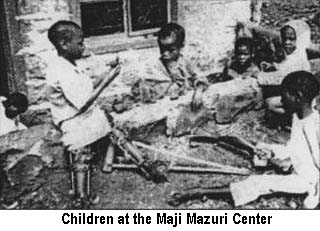

Eventually the mothers, with help from neighbors, built a modest community center (called Maji Mazuri) for meetings, rehabilitation, skills training, income generation, games, awareness-raising theater skits, and child-care. The women also built a cooperative bakery. The initiative for disabled children became a spearhead for community development. |

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA