Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For , By and With Disabled Persons

Part Two

CREATIVE SOLUTIONS FOR WALKING

AND FOR LEG AND FOOT PROBLEMS

CHAPTER 11

Leg Braces for David:

The Need to Solve Problems as Equals

Making Sure Aids and Procedures Do More Good Than Harm

When I (David Werner) was a young boy, I gradually developed a strange, waddling gait (way of walking). Often I fell down and twisted my ankles. At school, some of the other children, to tease me, imitated the way I walked. They said I looked and moved like a duck. Soon I was nicknamed "Rickets," and for years everyone called me that, even some teachers . . . even my friends. I hated the nickname and the teasing. But, in some ways, they may have helped me to become a better person. I came to feel a kind of empathy for other kids who were belittled or made fun of. All my life I have been a defender of the underdog.

When I was about 10 years old my parents, who were increasingly concerned about the problem with my feet, took me to a foot doctor. In those days, no one knew that my strange gait and frequent falls were early signs of progressive muscular atrophy (a hereditary condition which was diagnosed years later as Charcot-Marie-Tooth Syndrome).

Torture by arch-supports. The doctor examined my feet. Finding them weak and floppy, he prescribed arch-supports. An "orthotist" (brace maker) across town would make them.

When the arch-supports were ready, the orthotist put them on my feet. "Do they hurt?" he asked. "No," I said. So I was sent home with instructions to wear them every day.

I hated the things! - not because they hurt, but because it was harder for me to walk with them than without them. They pushed up on my arches and bent my ankles outward. I sprained my ankles more than ever.

I tried to protest, but nobody listened. After all, I was a child. "You have to get used to them!" I was told. "Who do you think knows best - you or the doctor?"

So, mostly, I suffered in silence. I hobbled around with swollen, black-and-blue ankles. Whenever I could, I secretly took the arch-supports out of my shoes and hid them. But when I was caught, I was punished. I was made to feel naughty for not doing what was "best" for me.

Metal leg braces: worse still! Several years later, as my walking got worse, I was prescribed a pair of metal braces (calipers). They held my ankles firmly, but they were heavy and uncomfortable, and they made me more awkward than ever. I hated them, but wore them because I was told to.

One holiday, I took a long walk in the mountains. The braces rubbed the skin on the front of my legs so badly that deep, painful sores developed, down to the bone. It took me months to recover. I refused to wear the braces again.

Personal Efforts to Prevent Deformity and Contractures

As the years went by, my feet became increasingly deformed. The inward-turning (varus) dislocations of my ankles got worse, making walking more and more difficult and painful. But, after my childhood experience with hurtful orthopedic appliances, I was unwilling to try braces again.

More years went by. I became a biologist, then a school teacher. In my late twenties, I began to work in the mountains of western Mexico as a founder and facilitator of Project Piaxtla, a community health program run by villagers. Fifteen years later, Piaxtla gave birth to PROJIMO, the Program of Rehabilitation Organized by Disabled Youth of Western Mexico.

Throughout this time, although walking was uncomfortable and difficult for me, I knew that to combat contractures and be able to continue walking, it was important for me to walk a lot.

At PROJIMO, we had learned that one way to help children combat varus contractures of their feet was for them to practice walking on boards placed side by side in an open "V". This stretches their feet and ankles in the opposite direction of the contractures. For myself, I did a similar sort of corrective exercise by hiking on well-worn mountain trails. Walking on such V-shaped (or U-shaped) trails was easier than walking on flat ground (where my ankles tended to double over side-ways). After walking for 2 or 3 hours on such trails, my feet and ankles were sore from all the stretching - but walking was easier for me, even on a flat surface. (I had discovered this trick of walking on a V-shaped trail in childhood.) In PROJIMO we found it could help other children with weak ankles and varus contractures. So, we included the following suggestions in the book Disabled Village Children:

|

As much as possible, try to make exercises functional and fun.

|

|

|

|

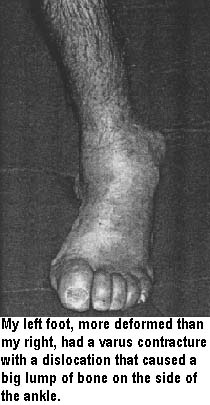

As I began (unwisely, in terms of my physical health) to spend more time writing and less time walking, the contractures and deformities of my feet grew worse. My left foot, especially, became very dislocated at the ankle.

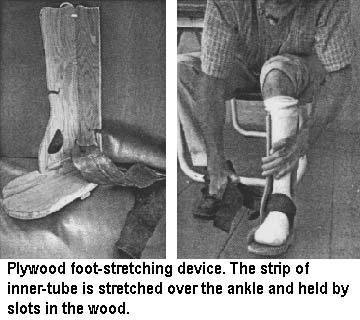

A plywood foot-stretching device

Still unwilling to try braces again, but needing to decrease the contractures of my left foot, I created a device to wear while sitting and writing. It stretched my ankle and foot in the opposite direction of the contracture. Made of plywood and a strip of rubber inner-tube, the device did help somewhat, but it became very uncomfortable if I wore it for long. So I did not use it much. At best, it perhaps helped to prevent the ankle deformity from advancing as fast.

Designing Braces that Actually Help: Marcelo as a Partner in Problem-Solving

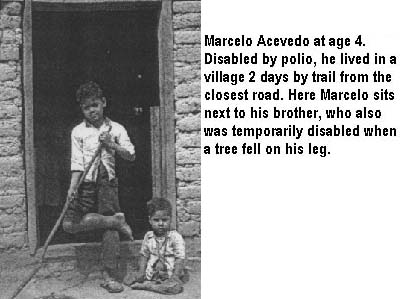

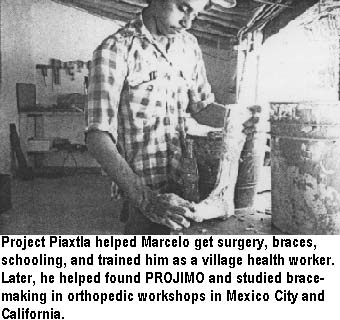

PROJIMO's first brace maker was MARCELO Acevedo, a village youth whose legs were paralyzed by polio as a baby. I first met Marcelo when he was 3 years old, in a remote mountain village called Caballo de Arriba (Upper Horse). Unable to walk, he dragged himself about on his arms. The Piaxtla health team helped Marcelo to get braces and crutches, and arranged for him to go to school in the village of Ajoya, where Piaxtla had its base. (There was no school in his own village.) When he was 14, the Piaxtla team trained Marcelo as a village health worker. So he was able to return to his village with an important skill.

When PROJIMO began in 1981, Marcelo was one of its founding members. Arrangements were made for him to apprentice in a brace shop in Mexico City, where he learned the basics of making orthopedic appliances. Volunteer orthotists (professional brace makers) who visited PROJIMO helped Marcelo to upgrade his skills. A careful and creative worker, Marcelo soon became an outstanding technician and designer. He has since learned how to make artificial limbs, wheelchairs and other assistive devices.

One day, Marcelo watched me walking with difficulty across the PROJIMO yard, and approached me on his crutches. "David," he said, "I think you could walk much better if we made you some leg braces."

"Leg braces!" I exclaimed. "Not on your life! I was tortured enough with those things as a child. I know they help some kids walk better. But for me they were torture! They made me walk worse."

"Maybe the braces you used as a child didn't work because the doctors and brace makers simply prescribed and made them, without including you in developing them," said Marcelo. "What do you say if you and I work together on designing braces for you, and we keep experimenting until we create some that work?"

"And if they don't work ...?" I asked.

"Then at least we will have had the adventure of working together and trying our best," said Marcelo. "You helped me to walk. Now it's my turn with you." What could I do but agree?

STAGES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PLASTIC BRACES: THE FIRST DESIGN

On evaluating my need for bracing, we felt that the two biggest goals were to stabilize the foot-drop (front of the foot hangs down and is too weak to lift) and varus (inward turning) dislocation. Marcelo thought that a plastic brace could help to hold my feet in a better position, allowing a more stable, comfortable gait. He took plaster casts of my lower legs, modified the positive (solid) molds, and stretched hot polypropylene plastic over the molds to form the braces (see p.90).

The first design was similar to a standard plastic AFO (ankle-foot orthosis) except that a broad area on the outside of the ankle was left to hold the ankle in place and keep it from dislocating outward.

The plastic just above the ankle was cut back narrow enough to allow the brace to bend upward a little at the end of a step. This permitted a more comfortable, easier gait.

I tried the braces and, at first, liked them. They held my feet in a better position, and I could stand and step more firmly. But, when I began to walk longer distances, I ran into problems. The upward flexibility of the braces caused pain inside the ankle and mid-foot.

Worse still, the pressure of the varus ankle against the plastic became quite painful. Because the sideways contracture at the ankle made complete straightening of the heel impossible, every time I put my weight on the foot, the ankle tried to bend outward.

The dislocated lump on the side of the ankle pressed painfully against the plastic brace. We tried putting a soft pad in the brace over the lump, but that didn't help much.

One time, on a long hike, the pressure on my dislocated left ankle against the plastic became so painful that, to relieve it, I pushed a folded handkerchief between the brace and the outer side of my leg above the ankle. This immediateiy helped to reduce the pressure against the lump and it lessened the pain.

On returning to PROJIMO, I showed Marcelo how I had relieved the pressure on the lump at the ankle. Together, we set about designing a new brace with that modification built in.

THE REVISED DESIGN: PLASTIC BRACE WITH PRESSURE RELIEF ON THE DEFORMED ANKLE

A brace was needed that would exert pressure in 3 areas of the leg, in order to hold the leg and heel in as straight a line as possible.

|

The first, more standard design put pressure on the:

Because the heel could not be straightened completely, the pressure on the outer ankle was great, and painful with each step. |

The new brace was shaped like this with the plastic coming clear around the outer (lateral) side of the leg. This prevented any upward flexing of the foot, thus reducing my mid-foot pain.

The wide side of the brace at the ankle allowed a long, broad pad to be placed so that it pressed against the whole side of the leg. This helped straighten the ankle and heel, while taking pressure off the ankle-bone. |

The new braces did eliminate the painful pressure against my ankles. But I still had some mid-foot pain. Also the completely stiff ankle of the brace made for an awkward, choppy gait, and pushed my knee backward uncomfortably at the end of the step.

Rocker-bottom, inward-sloping shoes. To overcome the above problems, we experimented with rocker-bottom shoes. To find out how much rocker-effect was needed and at what position on the shoes, Marcelo first taped small blocks of wood to my shoe-soles, and asked me to walk on them. We tried different positions and heights until we found those which were most comfortable.

We also tried wedging up the outer (lateral) side of the shoe. We found that by making the outer edge of the sole thicker than the inner edge, the varus deformity of my feet was better corrected and walking was more comfortable.

A PERSONALIZED PLASTIC BRACE INSIDE A ROCKER-BOTTOM SHOE-FINAL RESULTS:

The angle at the ankle lets the foot tilt down more than 90 degrees (planter-flexion). This makes allowance for the drop-foot contracture and permits easier walking.

Results: After a long process of trial and error, in which Marcelo and I worked together through a problem-solving process, we arrived at a combination of custom-made braces and adapted shoes that have given me new freedom. I can now walk up to 15 miles a day with little discomfort. I walk better today than I could 30 years ago. And I owe these successful results not to the interventions of orthopedic specialists in the USA, but to a disabled village brace maker who worked closely with me as a friend and equal.

Simple Tricks for Experimenting with Modified Shoes

ADJUSTABLE ROCKER-BOTTOM. I have been through many sets of braces and shoes in the years since Marcelo and I first developed braces that more or less met my needs. In addition to Marcelo and Armando from PROJIMO, a young North-American brace maker, Oliver Bock, has also worked closely with me to help fit me with suitable braces and shoes. Oliver first visited PROJIMO as a teenager, became fascinated by brace making, and later studied in an orthotics training program in California. But although he now has professional training, he still makes a point of working closely with his clients, involving them in an innovative, problem solving process. Over the years Oliver has also made many trips to PROJIMO, to help teach brace making to village rehabilitation workers from other programs, and to help the PROJIMO brace makers up-grade their skills. Again, he shares new ideas and techniques more as a friend and equal than as a formal instructor.

When I need to adapt new shoes or modify old ones, I now use a couple of simple methods to provisionally try the modifications I think I may want.

To create the effect of a temporary rocker-bottom sole, I used a U-shaped piece of polypropylene plastic.

The U fits snugly on the bottom of the shoe, and can be tied on firmly with a string that passes through holes in the arms of the U.

The strings pass over the top of the shoe and behind the heel, allowing the shoe to be removed without removing the U. The U can be easily moved backward or forward, to test for the most beneficial position. (I find that just one centimeter of change can make a big difference in comfort and ease of walking.)

ADJUSTABLE WEDGE. To experiment with different wedging on the shoe, I make a deep horizontal cut in the sole of the shoe. I pry this open with a screwdriver and slip a small wedge of wood, rubber, or metal into the slot. I can easily move the wedge backward or forward, or use wedges of different thicknesses.

Each of these methods permits me to try out a series of temporary modifications for hours or days, to decide which are most helpful.

Thanks to help from peers and friends, today my disability is less of a handicap than it used to be.

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA