Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

Part One

THE PURPOSE OF SPECIAL SEATING:

Freedom and Development, Not Confinement

Introduction to Part One

A Child is Not a Sack of Potatoes

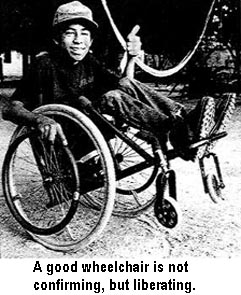

Wheelchair riders often protest when people say they are "confined to a wheelchair" or "wheelchair bound." For them, a good wheelchair is not confining but liberating. It frees them to go where they want and to do what they choose. It permits them to accomplish more than they could do otherwise. It releases them, at least in part, from the handicapping effect of their disability.

The same is true - or should be - for special seating. It should not be confining, but liberating. The purpose of a special seat should not be to rigidly hold the child in a position that looks "good," but rather to help the child to learn to sit in a position that is beneficial. A beneficial position is not necessarily one that looks normal. Rather, it is one that helps the child to stay healthy and to do what she wants or needs to do more easily and effectively.

Usually the best special seat is one that provides the least amount of support needed to help the child do the most for herself.

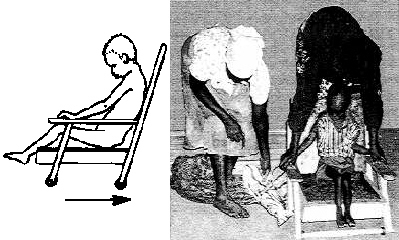

|

For a child whose body stiffens like this,

|

don't do this,

|

when all that is needed is this.

|

A child is not a sack of potatoes. Unfortunately, however, a lot of special seating is designed to hold children as if they were no more than sacks of potatoes.

Special seating, at its best, does not simply hold a child in a desirable position (although this may be a starting point for some children). It can sometimes help a child to improve balance, sit with less need of support, and learn new skills. In this chapter we will see examples of ways that seating can be designed for and with specific children to help them to gain better head control, discover the usefulness of their hands, observe their surroundings, dress themselves, and even use their leg muscles in preparation for walking.

SPECIAL SEATING: FIT OR MISFIT?

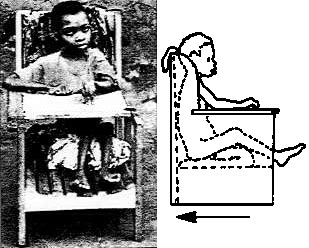

Special seating can be an important rehabilitation technology if it helps a disabled child to sit in a more self-controlled, more comfortable position, or if it enables her to do more things or learn new skills. However, in many programs you will see special seats that do more harm than good. The problem is not lack of concern. Often a lot of time, energy, and care have gone into making the seat. The crafts-person (perhaps a local carpenter) may be highly skilled. But two problems are common: First, the design was selected from an overly simplified "how to do it" book, and the seat is not suited to the child's particular needs. (This is especially true for children with cerebral palsy, whose combination of needs vary greatly.) Second, the seat is too big for the child. The following are photos of seats made for children with cerebral palsy. The photo on the left is from a brochure from Burundi (the same brochure with the photo of parallel bars we showed on page 11). The photo on the right is from a CBR program in Kenya which the author visited.

What problems do you see with these seats? (SIDE VIEWS)

Note that both of these seats are too big for these children. In the first, the child's knees do not reach the front edge of the seat, so her unsupported feet stick out in front. The second seat could fit 2 such children, side by side. in these oversized seats, the children tend to slip forward. As their hips extend (get straighter), the spastic stiffening of their bodies increases. The result is a poor position, discomfort, and loss of control for eating or play. Such misfitted seats can do more harm than good. Using a standard child's chair, or simply sitting the child in the corner, is likely to work better.

Above are a few examples of seating from the book, Disabled Village Children. Each seat works well for certain children ... but not for others! Especially for chiidren with cerebral palsy, it is best to use a trial and error approach.

The best guide is what makes the child happy and helps her do things better.

There are three main reasons why special seating is often inappropriate:

- There is a tendency to place too much emphasis on construction of the equipment and not enough on making sure it meets the child's specific needs and fits her well. Special seating, like all custom-made disability aids, should be approached through an experimental problem-solving process, by trial and error.

- A lot of instructional materials, especially those for community-level work, show pictures of a few special seats. But they lack adequate instructions for measuring the child or for translating those measurements to the seating design. (See Chapter 3.)

- In instructional materials, designs are often misleading or inappropriate. If a seat is built precisely as in a drawing, it may not be appropriate for the child shown (or, in some cases, for any child).

For example, here is a drawing from a brochure produced by a CBR training center in Asia. At first glance, the special seat appears well-fitted and appropriate. But look closer. Although it matches the child's size more closely than do the seats in earlier photos, the seat presents many problems for the child that is shown.

The problems are clearer when we look at the same seat from the side, as shown here:

- The sides of head-rest are too far forward. They block the child's vision to the sides.

- The seat belt is too high. It causes, rather than prevents, slumping. Also, the belt provides no sideways stability because it passes around the sides of the chair.

- The seat is too deep. The knees bent over its front edge force the child to slump with rounded back and extended hips: a tiring and harmful posture. It could increase spasticity.

- The back of the chair pushes the child's head forward, lowering his line of vision. This makes it harder for him to watch activities around him, which can delay his development (see page 293).

- Danger of falling. The chair tips back slightly but with no safety supports to prevent it from falling over backward. This is especially risky because the feet are on the ground. (There is no footrest.) A child with spasticity could easily push the seat over backwards.

If the child shown above has spasticity, the slouched position that the seat provides could trigger backward stiffening of the body, thus requiring the seat-belt to keep him in the seat. A few basic principles of seating and positioning of such children are shown below in simplified form. (Side supports and armrests, which may also be needed, are not shown in these drawings.)

|

The seat belt is in a bad position for this child. Positioned at waist level, it may worsen rather than prevent the slouching posture. |

To help pull the hips back and keep the back straighter, and to keep the hips bent enough to reduce spasticity, the belt must be low across her lap. |

By raising the front of the seat or putting a dip at the back, spasticity can sometimes be reduced so that a restrictive belt is not needed. |

To find out which of these - or other - options is likely to work best for an individual child, experimentation is necessary, paying attention to the child's wishes and responses.

A Great Variety of Seating Possibilities

When planning a special seat for a child, imagination is required to design and adapt a seat that:

- meets specific needs of the child (and whoever cares for her);

- fits into the local social and physical environment;

- is low cost, so the family or community can afford it;

- is simple and easy enough to make, so that the family can adapt or remake it as the child and her needs change.

A great variety of materials can be used: sticks, logs, wood, plywood, plastic, metal rod, cardboard boxes, paper, even mud.

Seats also range from simple to complex. The design depends on the child's particular needs and stage of development. Some seats serve mainly to keep spastic legs separated; others help a child sit in a more functional position. Some seats are designed to reduce muscle tone in a spastic child; others are designed to increase tone in a floppy (flaccid) child (see Chapter 4). Here is a sampling of different seating designs:

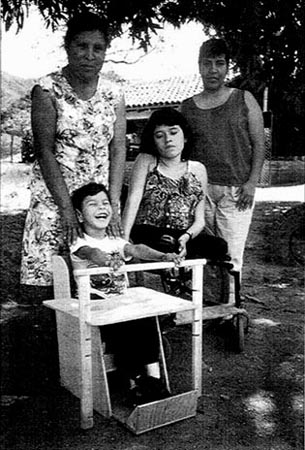

SPECIAL SEATING ON WHEELS

Wheels can be put onto special seats, for the benefit of both the child and her care-providers (mother, brothers and sisters, or others). The mobility (movement on wheels) achieved stimulates the child's development: exploration of her environment, enjoyment, physical coordination, self-reliance. And for the mother of an older, heavier child, being able to push her in a wheelchair, rather than have to always lift and carry her, makes moving her easier and protects her back.

Special seats can be built to fit into a standard wheelchair. Or wheels can be attached dfrectly to the special seat. Here are some examples of different forms of special seats on wheels:

The 10 chapters in Part One illustrate several innovative seating designs (such as "positive," or forward-sloping, seating), the use of unusual building materials (paper and mud), and the involvement of disabled children and parents as partners in the problem solving process.

For more special seating ideas, including use of straps and wedges to improve positions or reduce spastic patterns, see the book, Disabled Village Children. Or see Special Seating, by Jean Anne Zollars (see page 344). Jean Anne helped develop the measuring device for special seating that is discussed in Chapter 3.

DESIGNING CHILD-FRIENDLY SEATS FOR THE NEEDS OF THE INDIVIDUAL CHILD

Every Child's Needs are Somewhat Different

Designing a special seat for a child's unique combination of needs can be a challenging adventure. It requires an experimental approach, with as much involvement of the child and parents as possible, to figure out what design to use and what supports and other features may benefit or appeal to the child.

No one - including a disabled child - likes to be in the same position for very long. For example, if our knees are bent for a few minutes, we want to straighten them. If they are straight for long, we want to bend them. The body tells us that such change in position is healthy and necessary. It keeps our joints flexible and working well. Therefore, it is wise that we listen to the child and that we do not leave any child fastened in a seat (or standing frame or other assistive device) for too long. Most children (but not all) will find a way of letting us know how long is long enough.

It is also wise to design the seat so that it allows the child as much freedom and movement as possible, while making sure it provides the minimum amount of positioning and support needed to help the child sit up well and function.

The Fish-and-Pond Seat - for Changing Positions and Fun. When possible, special seating should allow and encourage the child to change position. Children need to learn to sit with knees both straight and bent (and should be able to change position often). This fish-IN-a-pond seat for straight-leg sitting easily converts to a fish-ON-a-pond seat for bent-knee sitting. The seat was designed by the British simplified technology wizard, Don Caston, who adapted it to this child's needs on a visit to PROJIMO.

|

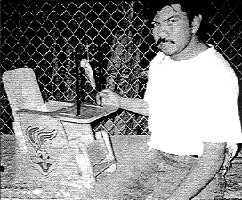

Making special seating and other assistive equipment attractive and child-friendly can make a big difference in how a child - and family - accept and make use of it. |

Juan Morales is a disabled young man who first came to PROJIMO for his own rehabilitation, and later set up an independent program in his home town. Here he builds a special seat for a child with cerebral palsy. Juan takes a lot of care in making the seats appealing to their young users. On this seat he has painted a colorful Bugs Bunny. |

SPECIAL SEATING FOR SWINGS

|

Village children make an enclosed swing in PROJIMO's Playground for all Children (see pages 288-289). |

Special seats can be built and adapted for a wide variety of circumstances, including playground equipment. For example, you can make a swing with an enclosed seat, so that a child who does not have enough hand or body control to sit in a standard seat can enjoy the fun and stimulation of swinging, like other children.

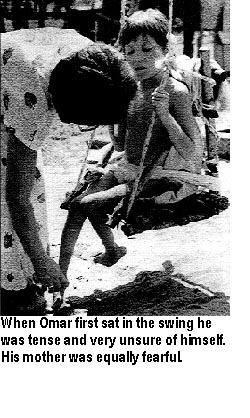

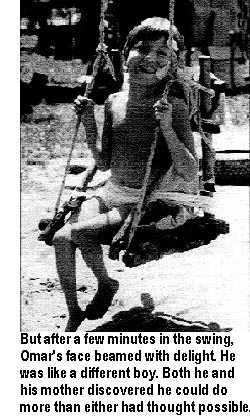

OMAR, a child with cerebral palsy, was brought by his mother to PROJIMO. His mother loved him a lot and wanted the best for him. But she overprotected him. When Mari suggested that Omar play in one of the enclosed swings in the Playground for All Children, at first both he and his mother were frightened.

But after just a few minutes in the swing, Omar was having a wonderful tfme. And his mother realized that her son could do more things than she had ever imagined. She said she would ask her husband to make a similar swing at home. Omar was delighted.

For other designs of enclosed swings and specially adapted swing seats, see pages57, 58and288. A swing seat made from an old tire for a girl with spasticity is described in Chapter 5.

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA