Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

Part Six

CHILD-TO-CHILD:

INCLUDING DISABLED CHILDREN

Introduction to Part Six

Helping Children Respond Creatively

to the Needs and Rights of the Disabled Child

Part Six of this book focuses on Child-to-Child activities, where disabled and non-disabled children interrelate and learn from each other through play, work, joint adventures, and creative problem-solving.

About CHILD-TO-CHILD and Discovery-Based Learning

Child-to-Child is an innovative educational methodology in which school-age children learn ways to protect the health and well-being of other children, especially those who are younger or have special needs.

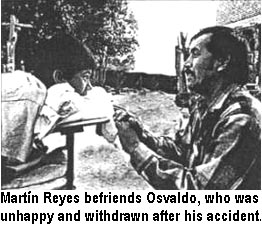

Child-to-Child was launched during the International Year of the Child, 1979. It is now used in more than 60 developing countries, as well as in Europe, the USA, and Canada. Many early Child-to-Child activities were developed in Project Piaxtla in Mexico, the villager-run health care program that gave birth to PROJIMO. Key to this adventurous approach was Martin Reyes Mercado, a village health promoter who worked with Piaxtla, and then with PROJIMO, for 2 decades. Martin now works with CISAS in Nicaragua, facilitating Child-to-Child throughout Latin America.

CHILD-TO-CHILD FOR DISABLED CHILDREN

Children can be either cruel or kind to the child who is different. Sometimes it takes only a little awareness-raising for a group to shift from cruelty to kindness. One of Child-to-Child's goals is to help non-disabled children understand disabled children, be their friends, include them in their games, and help them to overcome difficulties and become more self-reliant.

To give school-aged children an experience of what it is like to have a disability, a few of them can be given a temporary handicap. To simulate a lame leg, a stick is tied to the leg of the fastest runner in the class, to give him a stiff knee. Then the children run a race and the "lame" child comes in last. The facilitator asks this temporarily handicapped child what it feels like to be left behind.

Finally, all the children try to think of games they can play where a child with a lame leg can take part without experiencing any handicap: for example marbles or checkers.

A variety of activities can also be designed to help children appreciate the strengths and abilities of the disabled child, rather than to just notice their weaknesses. For this, skits or role-plays can be helpful. Here is an example.

Various role plays, games, and activities to sensitize children to the feelings and abilities of children with different disabilities can be found in the Child-to-Child chapter in the book, Disabled Village Children (see page 343).

The need to include disabled children in activities concerning disability

Many examples of Child-to-Child activities have been discussed in two of the author's earlier books: Helping Health Workers Learn and Disabled Village Children. (See more complete references to these books on pages 339 and 343.)

|

Some of the activities focus on what children can do to prevent accidents.

|

The books also suggest enjoyable ways in which school children can test the vision and hearing of those who are beginning school, as well as things they can do so that the handicapped child can participate and learn more effectively.

|

Unfortunately, in many countries, disability-related Child-to-Child activities are frequently conducted in ways that do not include disabled children in central or leading roles. Too often activities are about disabled children, not with them.

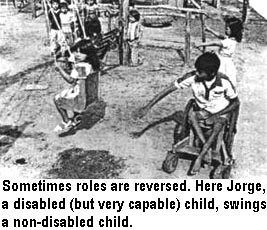

In Child-to-Child events led by PROJIMO, disabled children often play a central role. They make it a point to involve school-aged children - disabled and non-disabled together - as helpers and volunteers, and as "agents of change" among their peers.

Child-to-Child, at its best, introduces teaching methods that are learner-centered and "discovery-based," not authoritarian. It encourages children to make their own observations, draw their own conclusions, and take appropriate, self-directed action. This problem-solving approach emphasizes cooperation rather than competition.

PROJIMO makes an effort to get disabled children into normal schools. It uses Child-to-Child activities to help both school children and teachers appreciate and build on the strengths of disabled children. It designs activities to address the needs, barriers, and possibilities of individual disabled children in the school and community setting.

Disabled activists - some of whom are disabled school children - often take the lead in this process.

Encouraging Disabled and Non-Disabled Children to Play and Learn Together

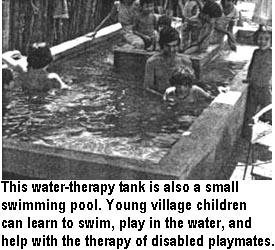

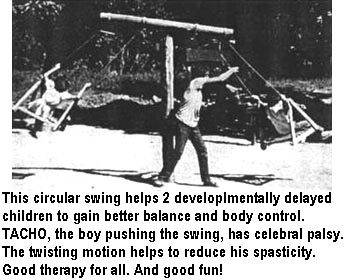

Two of the ways that PROJIMO encourages interaction between non-disabled and disabled children are the Playground for All Children and the Children's Toy-Making Workshop.

PLAYGROUNDS

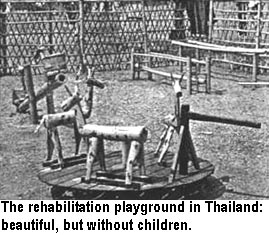

A great playground - but NO CHILDREN! The idea for making a low-cost rehabilitation playground came from a refugee camp in Thailand. That playground had a wide range of fine equipment, made with bamboo ... But when the author visited the playground, there was one big problem: NO CHILDREN! The playground was surrounded by a high fence with a locked gate. The reason, the manager explained, was that the local, non-disabled children used to play there, and constantly broke the equipment. So the local kids were locked out. Too often, however, so were the disabled children!

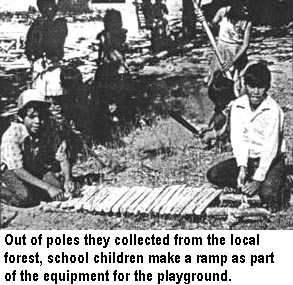

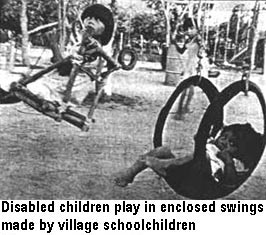

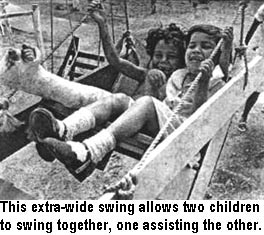

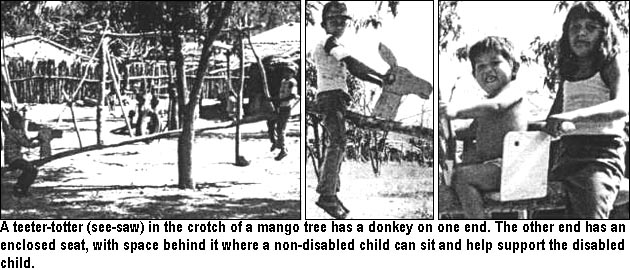

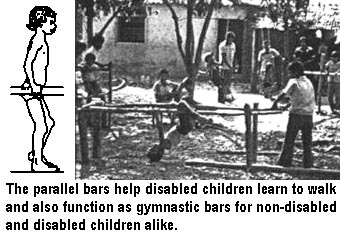

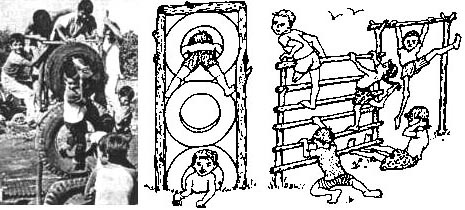

A Playground for ALL Children. To avoid such a problem, PROJIMO, in Mexico, invited local school children to help build and maintain a playground, with the agreement that they could play there too. The children eagerly volunteered, and the playground has led to an active integration of disabled and non-disabled kids.

|

|

|

|

|

|

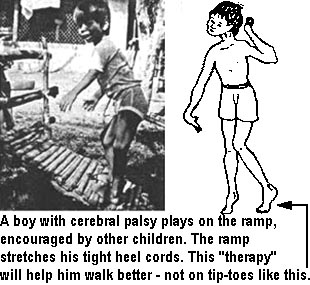

Making therapy functional and fun. When a piece of equipment in the playground seems to provide a child with helpful exercises, he or she is encouraged to play on it. And because it is easy to build with cheap local materials, the family can make one at home.

Good Ideas Spread. The idea of a Playground for All Children has spread to other villages. Here disabled and non-disabled children from Ajoya, where PROJIMO is located, help children in another town make their own playground.

THE CHILDREN'S TOY-MAKING WORKSHOP

The children's toy-making workshop at PROJIMO serves a number of purposes. It helps disabled young people to develop manual dexterity and useful skills. It attracts local school children to come make fascinating playthings together with disabled children. And it provides a supply of simple, attractive, early-stimulation toys and wooden puzzles. These are useful for children who are developmentally delayed or who need to develop hand-eye coordination. The sale of some of the playthings also brings in a modest income.

The toy shop is coordinated by teen-age village girls and disabled young women, who produce high-quality toys themselves and who guide the work of the younger children. They have an agreement with the local children: the first toy a child makes goes to a disabled child who needs it. The second toy she makes can be taken home for a younger brother or sister. (After all, early stimulation toys and activities enhance the development of any young child. This way, the process of children helping children - Child-to-Child - extends into the wider community.)

A school girl uses a rattle made in the toy-shop to help a multiply-disabled child respond to different stimuli and to use his eyes, ears, and hands. (Left)

A wide range of toys and playthings are made. Some of the simplest toys are rattles and brightly colored objects that can be shaken or hung in front of a baby or a child whose development is slow. (Right)

Other play-things include toys and games for the development of manual coordination, for learning relative sizes, shapes, and colors, and for learning numbers and letters.

|

The toy-makers also produce a wide variety of wooden puzzles, from simple to complex, to match the abilities and needs of different children. |

When a disabled child first comes to PROJIMO, she is invited to play with puzzles or toys to help her to relax and know that people care. It also helps the worker evaluate the child's mental, physical, and social abilities. |

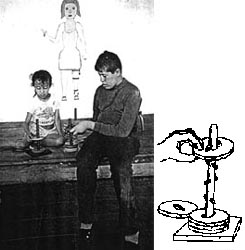

Lluvia - daughter of PROJIMO's disabled leader, Mari - teaches an older boy to use a toy, for better hand control. Brain-damaged from meningitis, the boy is mentally slow (but very friendly). He makes little use of his spastic left hand. To remove the colorful rings from the toy, he needs to rotate them past small pegs on the upright post. This helps him gain more skill with his hands. Lluvia makes it fun. Like her mother, she is a good teacher. |

CHILDREN HELP WITH THERAPY AND EQUIPMENT

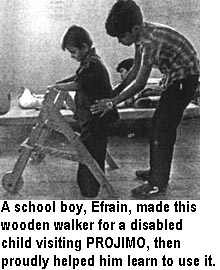

After school and on weekends, some of the school children not only work in the toy-shop, but they also help disabled children with exercises, play, and other activities. Sometimes a school child will help make a wooden walker or special seat for a disabled child, and then become involved in helping that child learn to use the equipment.

|

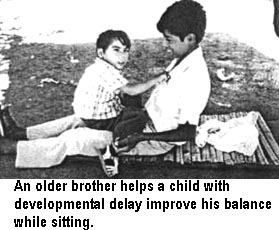

Children are encouraged to play with their disabled brothers and sisters, and to teach them how to help with exercises, stimulation, and skills-learning activities. |

Standing behind Jesica (with the walker), a school-girl called Gordi holds little Toni. Born with club feet, Toni spent several months at PROJIMO. (His mother had troubles and could not care for her child.) Gordi became very attached to Toni, and Toni to Gordi. Gordi bathed Toni, dressed him, and in a playful way helped with stretching exercises for his hands and feet. |

A therapist visiting PROJIMO, Ann Hallum, teaches the older brother of a girl who is disabled by polio how to do stretching exercises to correct a hip contracture. Many children are taught in this way to be "therapy assistants." |

CHILDREN ADAPT A SPECIAL SEAT FOR A CHILD WITH A VERY LARGE HEAD

JACINTO was born with spina bifida (see page 131) and hydrocephalus, a condition where liquid in the brain makes the head very large. Jacinto's mother, Cata, brought him to PROJIMO for rehabilitation, then decided to stay and work there for several months. Having a disabled child of her own, she was very able and loving with other disabled children.

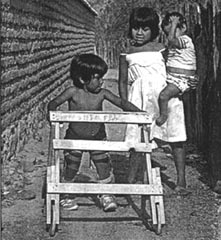

Juan, a disabled craftsman, made Jacinto a special seat with wheels so that Jacinto's mother, Cata, could push it. (She lived at the far end of town.) It had a removable table to hold toys and food. Above the table, Juan mounted a bar from which rattles and colorful toys could be hung, to encourage Jacinto to use his eyes and hands and lift his head.

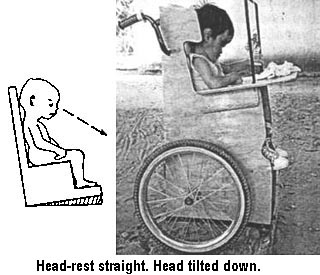

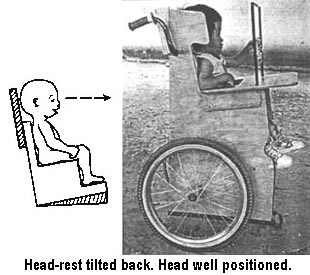

But the design had a problem. The seat-back and head-rest were both on the same plane, tilting back a little. For many children this would be OK.

But Jacinto's head was so big that the head-rest bent his head forward. This made it hard for him to keep his head upright. Because the hydrocephalus caused his eyes to angle downward, it was impossible for him to look up at the toys that were hanging in front of his face.

Solution. To allow Jacinto to lift his head more, the head-rest needed to be positioned farther back (behind the plane of the back-rest). Juan was busy on another project. So a couple of school boys who often came to PROJIMO to fix their bikes and help with odd jobs, offered to make the adjustments. They cut a rectangle out of the part of the seat back that supported Jacinto's head and mounted it further back by adding bits of wood on either side.

Then they put Jacinto in the seat. What a difference! Now he could lift his head and see the world around him. He could look at the toys hanging in front of him. The boy reached out to play with them.

The two "junior rehab technicians" felt proud that they had been able to help. They were eager to help more.

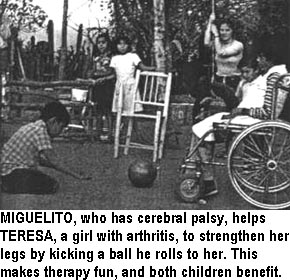

Disabled Child to Disabled Child

PROJIMO is based on a give-and-take approach, where disabled persons help and learn from each other. Peer assistance can - and often does - start quite young. A child with a disability not only tends to better understand the needs, feelings, hopes and fears of another disabled child, but can also be an excellent role model.

Several examples of ways that disabled children assist, teach, and care for each other have been seen in previous chapters. Chapter 32, for example, shows how CARLOS, a boy who has a combined physical, visual and mental handicap, helped another boy, Alonzo, learn to walk.

Part 6 of Nothing About Us Without Us tells a number of stories about ways that disabled children assist one another. In such relationships, often both the receiver and the giver of assistance benefit greatly.

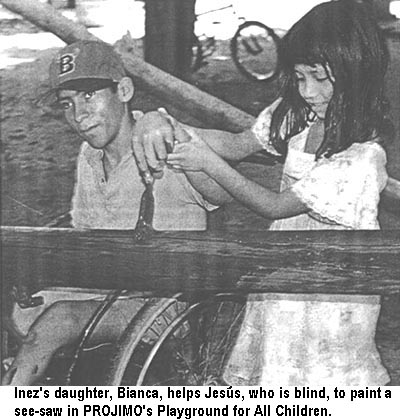

Chapter 45 describes JESUS, a boy with spina bifida who is also nearly blind. Jesus was first helped by his classmates, through Child-to-Child activities, to be accepted and treated more fairly by his teacher. Later, Jesus himself becomes a facilitator of Child-to-Child, helping two children with muscular dystrophy in another village to be appreciated and assisted by their classmates.

Chapter 46 tells how JORGE, a boy in a wheelchair, helps MANOLO, a mentally slow but physically strong teenager, to speak and act for himself. After his integration into PROJIMO, Manolo takes pride in assisting physically impaired children. Then a friendship develops between Manolo and LUIS, who has cerebral palsy but is mentally bright. By bringing together the brawn of Manolo and the brains of Luis, the two indulge in adventures which neither could have accomplished on his own.

Chapter 47 tells of how VANIA, a spirited 9-year-old girl with a spinal-cord injury, provides nursing care and friendly companionship to 6-year-old JESICA, who is similarly paralyzed.

Chapter 48 shows how the remarkable Peraza family - with 4 children who have muscular dystrophy, including SOSIMO - plays a leading role in a program run for and by disabled young people.

Another of these 4 children, DINORA, studies English with a disabled young teacher, so that she, in turn, can teach her disabled friends.

Chapter 49 explains how FERNANDO, a boy with cerebral palsy, is helped by MANUEL and other playmates to learn a variety of skills and to gain greater self-confidence.

Chapter 50 describes how MARIA, a mentally handicapped girl in Brazil, learns to provide care and therapy for EMA, a multiply disabled child.

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA