Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

Part Six

CHILD-TO-CHILD:

INCLUDING DISABLED CHILDREN

CHAPTER 49

Playmates as Therapists:

Helping Fernando Learn New Skills

In Chapter 45, we saw how Child-to-Child activities helped Jesus' classmates and teacher to better understand his needs and possibilities. Here, we see how the playmates of another disabled child succeed in helping him to learn useful skills and activities that adults had been unable to teach him.

FERNANDO is slow to trust adults. He has good reasons. Since he was a baby, he has been hurt in different ways by grown-ups who wanted, in their own way, to help him.

Fernando's mother grew up in a small village, but in her early teens she went to the city to study. There she was courted by a young man, whom she soon married. Months later, a baby was born and they named him Fernando. He was a lovely child with golden curls. At first, the signs of his cerebral palsy were not very obvious.

After three difficult years, the marriage broke up. Both parents fought to keep the child. One night, Fernando's father came home to the village, very drunk. He kidnapped the little boy from the mother's family at gunpoint. But as the child grew, spasticity and other signs of cerebral palsy became clearer. He began walking at the age of 4, with a spastic, knock-kneed gait. He has never been able to talk. Unwilling to accept that his son was disabled, his father took him to one doctor after another, seeking a cure. Some doctors said the boy's condition was hopeless: nothing could be done. Others performed costly tests and prescribed costly medicines. Unwilling to raise a son whom he considered "minusvalido" (less valid), his father took Fernando back to his mother.

But by this time, the boy's mother had another lover who, like his father, did not want an "invalid." In the end - as often happens - Fernando's grandmother took the child in. She loved him and wanted the best for him. But her own husband had died (of tuberculosis and alcoholism), and she had trouble maintaining her small store to make ends meet.

Fernando's grandmother lives in Ajoya, where PROJIMO is located. The PROJIMO team offered her advice and, when Fernando was 5, encouraged her to put him in kindergarten. Year after year, he attended school, but he never got beyond the first grade. The boy was alert and in some ways seemed intelligent. But he had a learning-disability with talking and reading. After repeating first grade for 5 years he still could not write his name.

Rather than focusing on the "3 Rs," the PROJIMO team thought it might be more enjoyable and useful for Fernando to learn some practical skills. They made repeated efforts to include the boy in activities at PROJIMO: in the Playground for All Children, and the Children's Toy-Making Workshop. But even at age 11, the boy was still very timid, especially around adults.

One day when a physical therapist was visiting PROJIMO, Fernando's grandmother took him there for another evaluation. Terrified, the boy clung to Grandma's dress, his head down. Trying to win his confidence, Mari asked him if he would like to play on the swings or the merry-go-round. Fernando shook his head "NO!" and burst into tears at the thought of it. He was still very fearful of adults.

Playmates as Therapy Helpers

The PROJIMO team thought that Fernando's manner of walking might be improved with gait and balance activities. But despite their best efforts, Fernando refused to cooperate.

One day, Mari, who has helped to facilitate Child-to-Child activities with school-aged children, had an idea. "Fernando is so fearful with us adults," she observed, "even when we try our hardest to befriend him. Yet, outside his house, I often see him playing with other little boys with whom he is wild and fearless. Why don't we invite his young friends to come to PROJIMO, and bring Fernando with them? We can explain some play activities to his friends that could help Fernando improve his walking and balance. Maybe they can also get him involved in the toy-making shop, where they can all learn to make and paint toys together. That way Fernando could start learning useful skills."

Everyone thought this was a splendid idea. Conchita talked to Fernando's young friends, and to their mothers. Fernando's playmates were excited with the idea and wanted to help.

The Board-Walk Balance Game

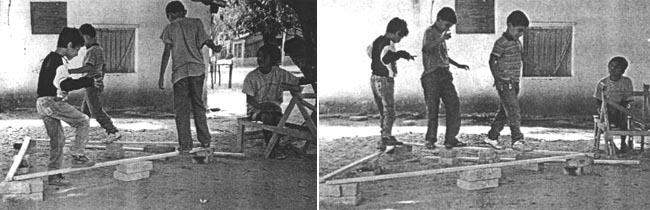

The next day the two young boys, Manuel y Chito, arrived at PROJIMO, followed - somewhat nervously ~ by Fernando, who lurched awkwardly from side to side as he tried to keep up. Mari suggested a game to help Fernando improve his foot-control and balance. Directing from her wheelchair, she asked the children to bring several boards down from the loft, and to place them over bricks to form narrow walkways.

Fernando, following the example of his friends, helped to carry the bricks and place them on the ground to support the boards. This was not easy for him. But somehow he managed to bend down, pick up the bricks with his spastic hands, carry them with his scissored gait, and place them under the giant fig tree. This way, not only the play-therapy activities, but also his involvement with his playmates in preparing the equipment, helped Fernando to develop body control.

When the "boardwalk" was in place, Mari asked the children to "follow the leader," walking back and forth on the boards. The 10-inch-wide boards were about 6 inches above the ground. The two able-bodied boys bravely "walked the plank," and Fernando fearlessly followed. He tipped precariously this way and that, looking as if he would surely fall off. But, to everyone's amazement, he kept his balance, grinning happily as he followed his friends back and forth. Everyone applauded.

Mari knew it was a good idea to have started Fernando with an activity he could succeed at easily. It gave him confidence. But this was too easy. He needed more of a challenge. So Mari had the boys arrange 3 long boards, each only 2 inches wide, in a triangular path.

Mari challenged the boys to walk as many rounds on the boards as they could without falling off. Fernando, despite his wobbling back and forth, waving his arms wildly to keep his balance, did amazingly well. At first, he - and occasionally also one of the other boys - sometimes lost their balance. But he rapidly improved until he rarely lost his footing on the narrow board.

Mari laughed at herself. "I thought Fernando needed to improve his balance!" she declared. "But he has incredibly good balance - better than I had before my accident!" She realized that he needed - and had developed - exceptionally good balance to be able to walk and run with legs that only imperfectly followed his wishes.

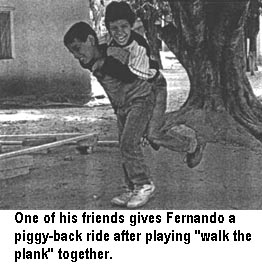

Important as these activities were for Fernando's balance and positioning of his feet, they were equally important for his growing sense of confidence among a mixed group of children and adults.

He very quickly appeared to be a very different child than the one who had arrived a few days before and had hung miserably to his grandmother's dress.

Spontaneous play and interaction with other children had as much therapeutic value, both physical and social, as did the specially designed activities.

Introduction to the Toy-Making Workshop

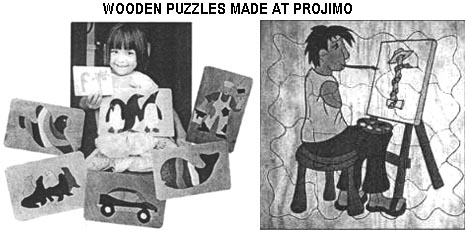

After their play on the "board-walk," the three boys were eager to do something different. Mari led the way to the toy-making workshop. This small shop was set up to involve disabled and non-disabled children together in making early-stimulation toys and puzzles, especially for children with developmental delay. (See pages 290-291.)

|

To interest the 3 boys in making toys, Mari asked the help of Manuella, a village girl who works in the toy shop. Manuella agreed to cut out wooden figures of animals or persons for each of the 3 boys, which they could sand and paint. The boys asked her to cut out figures of themselves. David (the author of this book) drew the boys, each posed in the position he wanted to appear in. |

Then the boys watched, fascinated, as Manuella cut out the figures on the electric jig saw. The figures emerged: Chito in a Karate pose, Manuel as a muscle man, and Fernando dancing. |

The boys carefully sanded the wood figures. With his spastic hands, Fernando had difficulty holding the figure and trying to sand it. But the other boys showed him how. Fernando did his very best. |

Next the boys painted the wooden figures of themselves. At first, Fernando had trouble holding and controlling the brush, and Manuella helped him by guiding his hand.

At last the boys finished painting the figures of themselves, and held them up with delight.

Although Manuel and Chito greatly enjoyed the activities themselves, they also took their job of helping Fernando to learn new skills quite seriously, and they felt proud when they saw him manage to do new things.

Making other toys. The children wanted to make other toys in the workshop. They asked Fernando if he wanted to make an animal, and began to name different kinds: A chicken? A dog? A cow? A cat? A raccoon? Fernando shook his head "No!" at each suggestion. Then the boys said "A Horse?" Fernando grinned and nodded. Chito and Manuel said that they, too, wanted to make horses. Excited, Fernando had yet another idea, but unable to speak, he had trouble communicating it. Everyone asked him questions about other animals or figures he might want to make. He kept shaking his head.

At last, Fernando made a gesture, as best he could with his spastic hands. It was something like this.(Left)

"He wants a rider on his horse!" cried Manuel.

"Then a horse and rider you will have!" said Manuella. She created a simple design. The rider was made of 3 pieces of wood: the body and two legs. The movable legs were attached to the hips with a small nail, so that the rider could be seated firmly on the horse.

Of course, all of the boys wanted a horse and rider. Again, they sanded and painted them lovingly. This time, one of the boys held the pieces while Fernando carefully painted them. He now seemed to have more hand control, which perhaps came partly from greater confidence.

This Chapter continues to the NEXT page

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA