Work and Proposals by Japan National Group of Mentally Disabled People

Naoyuki Kirihara

Steering Committee Member, Japan National Group of Mentally Disabled People

1. Opinion based on overall damage caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake

It seems that on account of the series of disasters stemming from the March 11, 2011, Great East Japan Earthquake, major issues that Japan had put off dealing with suddenly came to light. One of these issues was persons with disabilities. The Japan National Group of Mentally Disabled People responded to the earthquake as an issue of respecting the lives of persons with disabilities and anti-discrimination, as we always did, not out of an awareness of assistance for the vulnerable during disasters.

2. Response by the Japan National Group of Mentally Disabled People

The Japan National Group of Mentally Disabled People (the Group) checked on the safety of people along with sending letters of condolence, mainly to members in Tohoku (Northeast Japan) , Kita-kanto (Northern Kanto region) , Hokuriku (region west of Tokyo) , and determined that everyone was fine. However, that alone was probably insufficient to ascertain actual conditions, and the Group worked to participate in a mailing list mainly for medical practitioners, to dispatch staff to the Miyagi Support Center in the disaster area and the Fukushima Support Center for Persons with Disabilities Affected by the Disaster, and to ascertain actual conditions through the Kokoro No Pia Sapoto (psychosocial peer support) phone counseling program, undertaken by the Miyagi Seishinshogaisha Dantai Renrakukaigi (Miyagi Liaison Committee for Organizatios of Persons with Psychosocial Disabilities) , which received support from Yumekaze Fund. On account of the dispatch of personnel, it was possible to hear the stories of several persons with psychosocial disabilities at emergency shelters, etc. One person said that he had been driven out of the emergency shelter because of having health nurses and doctors come to him.

In the April 21, 2011 edition of the Mainichi Shimbun Newspaper, there was the story of a man with a psychosocial disability who became aggressive and had problems with the staff managing the facility as his condition deteriorated because of life as an evacuee and the shock of his family's home being flooded. For this and other reasons, it was understood that there was the possibility of persons with psychosocial disabilities being excluded. Furthermore, there was a report that when it was discovered that an evacuee was from a psychiatric hospital, the emergency shelter and operator of the evacuation bus refused to provide services, and in another case the evacuee was ultimately locked out of the shelter.

< Figure 1>

Medical professions desperately tried to connect people to medical care, but there were cases when this resulted in problems. After the earthquake, psychiatrists and clinical psychologists visited the various shelters. After a while, one emergency shelter posted a “No Counseling” sign, which drew a lot of attention. This is one example of people affected by the disaster objecting to forced support and non-humanitarian intervention. After that, one pediatrician released a paper with the following comments, “there was confusion since the psychiatrists dispatched from the various prefectures to provide support and teams from psychiatry schools at universities worked independently, and even when they held meetings, they could not reach agreement,” “in-human surveys driven by eager for fame were conducted,” and “one member of a team from psychiatry school stated, ‘since our team is a self-sufficient team, we did not interact with other teams.'” On April 20, 2011, the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology called attention to the issue by releasing the Emergency Statement On Surveys and Research in the Area Affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

The Group thought the above type of problems could occur; in particular, there was the danger that psychiatric hospitals could benefit from this. The Group confirmed that there had been no change in our basic stance of demanding not only earthquake countermeasures but also a society in which persons with mental illnesses can live.

3. Issues that came to light since directly after the disaster

On March 17, 2011, it was reported that fifty of the patients who had evacuated from Futaba Hospital died one after another. At first it was reported that, “when patients evacuated, they were not accompanied by doctors or nurses, and when they reached the emergency shelter, they were found to be severely malnourished,” but it became clear that when the patients evacuated on March 12, they were accompanied by the head of the hospital, and a correction to the article was later issued. Because of this, there was a misunderstanding that occurrence of the Futaba Hospital incident itself was groundless. However, various episodes came to light in the April 26 Mainichi Shimbun Newspaper and Juntaro Oda's Seishinbyoin ni Homurareta Hitobito (People Buried in Psychiatric Hospitals) (2011) . Although rescuers said that there were still elderly in the Futaba Hospital, government officials insisted they had heard from the police that the evacuation had been completed. At least on the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth, there were no doctors or nurses. A corpse with a death certificate dated March 12 was found at the Futaba Hospital on April 6. If one connects the various points, such as patients being abandoned, elderly with dementia being left in bed, and the construction of a nuclear power near Futaba Hospital, one can see a problem of the discrimination against persons with disabilities.

In addition, some of the patients transferred from Futaba Hospital were also in a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo. On March 15, 2011, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) issued a notification on being able to accept transfer patients even if doing so would result in the hospital having more than the permitted number of patients (“Handling Insurance-covered Medical Care, etc., Following the 2011 Tohoku Pacific Ocean Earthquake and Northern Nagano Earthquake” issued by the chief of the Medical Economics Division within the Health Insurance Bureau and the chief of the Division of the Health for the Elderly within the Health and Welfare Bureau for the Elderly of the MHLW). Since beds of hospitals were almost full, and the number of beds were insufficient because of accepting transfer patients, some transfer patients stayed in hospital gymnasiums and on futons laid on floors. However, while hospitals affected by the disaster demanded to be able to transfer their patients, almost no measures were taken for outpatients. It is natural that hospitals affected by a disaster may not be able to care for hospitalized patients, but it is likewise hardly possible that they can provide sufficient outpatient services. This reveals the stress on hospitalization for psychiatric care.

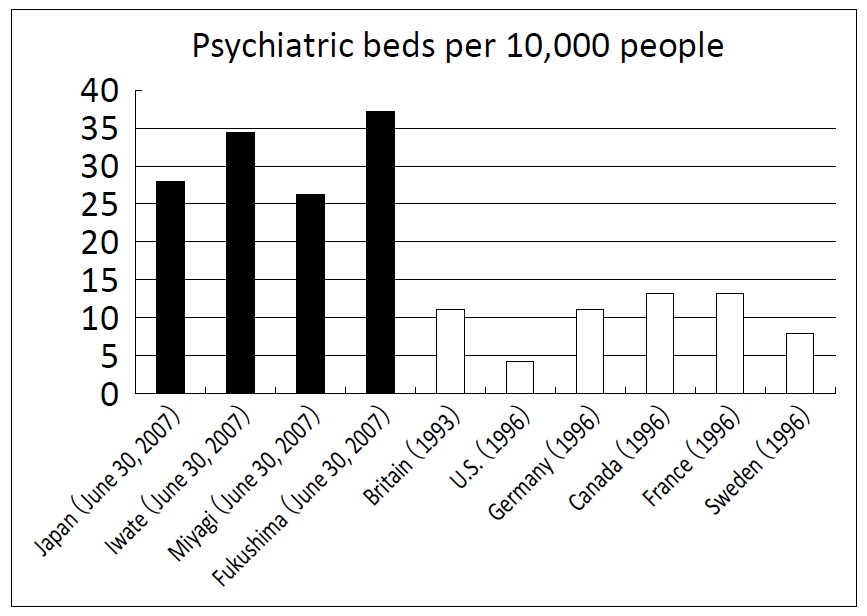

According to the World Mental Health Statistics, first compiled by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001, Japan accounts for 18% of the psychiatric beds throughout the world (1.85 million). Seishinhokenfukushi Shiryo (Mental Health Welfare Material) - Summary of June 30, 2007 Survey, compiled by the Mental Health and Disability Health Division, Social Welfare and War Victims' Relief Bureau, MHLW, there are 27.93 psychiatric beds per 10,000 people in Japan, with Fukushima having the greatest ratio of 37.0 beds per 10,000 people. (Figure 2)

At the International Human Rights Seminar on Earthquakes (sponsored by the Japan Federation of Bar Associations) , held on June 24, 2011, Ajith Sunghay of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, noted that “problems in Fukushima are not earthquake and disaster problems, but issues related to arbitrary detention. Reconstruction should not mean rebuilding society but creating an inclusive society, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities must be the standard for this. I recommend that you report the situation to the working group of arbitrary detention of Human Rights Commission.” Placing the elderly with complications in psychiatric hospitals is considered a problem in terms of international human rights.

(Text)

(Text)

< Figure 2 >

4. Proposals regarding the future

As Japan National Group of Mentally Disabled People, we would like to give priority to the lives of patients who have been forcibly hospitalized in psychiatric hospitals. Second, we are critical of turning things into medical issues by trying to solve problems including the exclusion of people from evacuations and emergency shelters through medical treatment, and we should try to respond by separating evacuees as evacuees and patients as patients. Third, it is the central government's responsibility to ensure the right to evacuate during emergencies. Fourth, it is necessary to establish criteria for standard medical supplies and an official storage system because it was difficult to obtain medicine as supplies were minimal. In addition, many of the elderly hospitalized for long periods, which was a problem in Fukushima, did not have a certificate for persons with disabilities, therefore it was impossible to ascertain the actual number of persons with certificates for persons with disabilities by simply counting them.

However, these are preconditioned on being able to handle problems within the framework of a disaster countermeasure. In Miyagi, which was hit by the disaster, a large number of psychiatric clinics were established in the urban district of Sendai, but in the suburbs of Ishinomaki, some psychiatric clinics had to close down. In the final analysis, this was because of the problem of gaps. The same is true with nuclear power plants, the existing problem is too large. Even though this came to light because of the disaster, it is not something that can be resolved within the framework of disaster countermeasures. In other words, there is a need for a form of politics that does not ignore the opinions of citizens working to resolve existing problems.

Reference material

Oda, Juntaro. Seishiniryo Ni Homurareta Hitobito - Sennyu Rupo Shakaiteki Nyuin. Tokyo: Kobunsha, 2011

Hyodo, Akiko. “Futaba Byoin Jiken” Wo Megutte. Jokyo June & July Combined Number. Tokyo: Situation Online, 2011

Hyodo, Akiko. Futaba Byoin Jiken Wo Megutte - “Seishinbyoin No Nihon Kindai” To Iu Rekishi Kara No Mondai Teiki. Network News 26, 2011

Yamamoto, Kiyoshi. Hisaichi Kara (Jidai Wa Kawaru) . Japan National Group of Mentally Disabled People News 37 (2) Tokyo, 2011