Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For , By and With Disabled Persons

INTRODUCTION

Disabled Persons as Leaders in the Problem-Solving Process

Go to the page "INTRODUCTION 1"

COMBINING THE BEST OF THE INDEPENDENT LIVING MOVEMENT AND CBR

In recent years, 2 major initiatives have evolved to help meet the needs, defend the rights, and promote the full integration of disabled people. These are the Independent Living movement (IL) and Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR). Active in many countries, both initiatives are a response to the discrimination, limited opportunities, inadequate services, and the need for self-determination that most disabled people experience in the world today.

The two movements have different origins. They also have different strengths and weaknesses. IL tends to be strong in areas where CBR is weakest, and CBR strongest in the areas where IL and disabled people's organizations sometimes are weak.

- Independent Living: The IL movement was started from the bottom up by disabled people themselves. It began in the Western industrialized countries. Through organizations like Disabled People International (DPI), it has gradually made headway in the so-called developing countries. IL's biggest strength is social action for equal opportunities, led by disabled activists. Its biggest weakness is that it is largely a middle-class movement that often leaves out the poor. Also, living "independently" (or alone) is a very Western value. In societies with a strong sense of community, rooted in extended families, living "inter-dependently" (together) may be a more welcome goal.

- Community Based Rehabilitation: CBR, as an international initiative, was launched by idealistic rehabilitation experts working with the World Health Organization (WHO). Its biggest strength is that it tries to reach all disabled people, especially those who are poorest and in greatest need. It has an all-inclusive plan, including both government and private initiatives. But, too often, disabled persons still are treated as objects to be worked upon, rather than leaders, organizers and decision makers.

One of the biggest challenges for disability workers today is to find ways to link the empowering self-determination of the Independent Living Movement with the broad outreach to poor people of Community Based Rehabilitation.

A good place to begin is by encouraging disabled persons to take over more of the organizational and service-providing roles in CBR programs. Where possible, disabled people's organizations can lead or advise the programs (while making an active effort to include the poor and voiceless). When disabled people learn to design and make assistive equipment, and to include the user in the process, success is more likely.

|

Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) Major STRENGTHS: Major WEAKNESSES: |

Disabled Person's Organizations Independent Living (DPI, etc.) Major STRENGTHS: Major WEAKNESSES: |

TROUBLE-SHOOTING THE TIDE OF INAPPROPRIATE TECHNOLOGY

Some readers may wonder if this book is needed. Lots of manuals and pamphlets on assistive aids and equipment already exist. They range from high-power rehabilitation engineering to simple (sometimes overly simplified) collections of helpful low-cost gadgets. Some of these guide books have marvelous designs. But too often, more importance is given to the equipment itself than to the persons who may use it. Precise steps for construction are spelled out as if the final product were an end in itself.

There is a need for guides that put more emphasis on listening to disabled persons' wishes and suggestions, jointly evaluating their needs, experimenting to improve the design of assistive equipment, and adapting it accordingly.

The author and his co-workers have visited rehabilitation programs, both hospital-based and community-based, in many countries. In program after program, we see well-made, attractive rehabilitation aids that simply do not meet users' needs. (The same is true for exercises and therapy.) Often equipment is beautifully and skillfully produced following detailed instructions in guide books or training plans. But for some reason the end results do not provide the expected benefits or satisfaction.

Not enough attention is paid to the specific needs, wishes, and ideas of the disabled person and family members.

At worst, assistive devices and exercises become dehumanizingly generic-ritualistic rather than functional. Around the world, two of the most poorly fitted disability aids are parallel bars and special seating. Here we will look briefly at parallel bars. We look at problems with special seating in Part I.

Parallel Bars: Therapy or Torture?

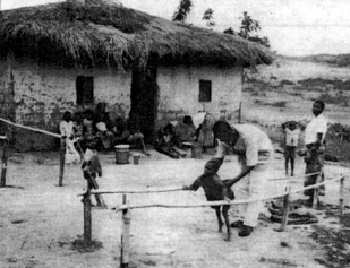

Photographs or drawings of rustic parallel bars made of poles supported by forked sticks appear on fancy brochures of major CBR programs around the world. But on close inspection, as often as not, the bars are inappropriate for the child using them.

Here is an example from an international brochure showing a CBR program in Burundi, Africa.(LEFT)

What problems can you see with the parallel bars used for this child's rehabilitation?

Correct! These bars are too high and far apart. The child, who has weak legs, must bear most of his weight on his arms. This requires enormous strength. Only powerful athletes can support their full weight on out-stretched arms, as when they perform the iron cross on gymnastic rings. To make a child with flail legs try to do this on bars can turn therapy into torture.

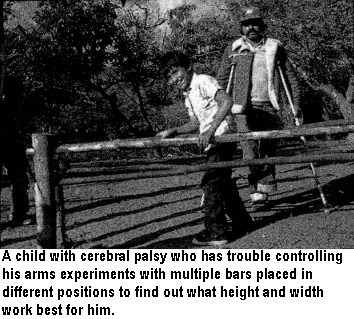

PARALLEL BARS should be built or adjusted to the height and width best suited for the needs of the individual. Usually, placing the bars fairly close together (so the person's arms are next to her sides), at a height so her arms are almost straight when standing upright, is the easiest and most functional position.

|

Often this position creates difficulties. |

Often this position works better. |

However, depending on muscle strength of the arms and hands, and other factors, some persons may find other positions or heights work better. For example:

|

A child who has strong legs but lacks balance may find it easier to walk with bars widely separated. |

A child with weak upper arms may find it easier to rest his forearrns on the bars. The bars will need to be elbow high. |

A child who tends to slump forward may find it easier to stand straight if the bars are high, so that he has to stand upright to rest his arms on them. |

It is essential to pay attention to the concerns of the person who will use the equipment. Even a child who can not speak may have ways of communicating her preferences (through tears or smiles).

It helps if bars can adjust to different heights for different children (and to find out what height works best for an individual child). Above(right) are 2 easy ways.

Usually the best person to decide what works best is the disabled person herself.

The Need for Careful Evaluation of Instructional Materials

Unfortunately, photographs or drawings of assistive equipment are not always critically evaluated before they are included in training manuals. Likewise, many instructional materials - and training courses - do not put enough emphasis on thoughtful, innovative participatory problem-solving. There has been a tendency, especially in community based programs, to deliver overly simple cookbook-like formulas for solving the needs of disabled people. High-level decision makers often try to find answers to the problems of marginalized people through impersonal, standardized shortcuts (the technological quick fix) rather than through listening and responding to the wishes of those in need. In sum:

Today there is too much doing things for people, not enough doing things with them ... too much giving authoritative instructions and following of recipes, and too little creative, participatory problem-solving. Disadvantaged persons are reduced to objects, things to be worked upon, tinkered with, corrected, and normalized, rather than treated as unique individuals to be empowered on their own terms. Too often the disabled person - especially the child - is left out of the problem-solving process.

There is an urgent need for training materials and courses to place less emphasis on following standardized instructions, and more emphasis on an observant, problem-solving approach in which the disabled person and family members are included and listened to as equals.

Disabled Persons and Groups Take the Lead in Designing Better Solutions

To solve their problems, disabled people in some countries have begun to play a leading role. Especially in the North, but increasingly in the Third World, disabled people have organized and are demanding a say in decisions that affect their lives. Through the Independent Living Movement (IL), and increasingly through Disabled People International (DPI), they insist on social rights and equal opportunity in such things as accessibility, education, employment, and recreation. They demand a leading voice in programs and policy-making that affect them.

In many countries, organizations of persons with disabilities have adopted the slogan: "NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT US." But while disabled activists insist on self-determination concerning social issues that affect them, they have been slower to assume leadership in matters of rehabilitation and technical aids. Even in the North, most disabled persons still follow the dictates of rehabilitation professionals fairly passively, without assuming much decision-making control. Disabled children, especially, have almost no voice in deciding what aids or equipment they are to use. This leads to errors in design that could be avoided. The author himself (David Werner) as a child was given orthopedic aids that did him more harm than good. Not until decades later did he at last obtain appliances that worked well for him ... thanks to a disabled village brace-maker at PROJIMO who included him as a partner in the problem-solving process (see Chapter 11).

ADAPTING SOLUTIONS TO THE LOCAL SITUATION AND INDIVIDUAL NEEDS

Throughout the Third World you see small children in adult-sized wheelchairs, and small thin adults in big, very wide, heavy chairs that they can barely move.

A common shortcoming of large rehabilitation centers is that aids and equipment tend to be standardized and "generic" (a few basic models are intended to meet the needs of all). This is especially true when equipment is purchased in quantity from commercial (or foreign) producers. When standard commercial aids are prescribed, too often an attempt is made to adapt the person to the equipment rather than the equipment to the person.

Disabled persons' needs differ, not only individually but also

according to local customs, living conditions and environment.

A potential advantage of a small community-based rehabilitation center is that aids and equipment can be custom-made for each individual as the need arises, often at remarkably low cost. Such an approach allows greater flexibility in terms of personal preferences, as well as adaptation to local circumstances, resources, and environment.

Four Women with Spinal-Cord Injury: Their Different Mobility Needs

Consider for example, 4 young women, all about 20 years old, each with a spinal-cord injury of the mid back. These are MIRA from a village in Bangladesh; RITA from the mountains in Mexico; LUZ from a city in the Philippines; and FARAH from Egypt. Each, after loving support and encouragement from family and community, got over her initial depression and is eager to continue with life, earn a living, and take an active part in society. But to do so, each needs an effective means of mobility: a way to move around and go where she wants to, in spite of paralysis of the lower half of her body.

Let us suppose that each of these young women - Mira, Rita, Luz, and Farah - has had the luck to be given a costly imported wheeichair by an international donor called "Wheels of Fortune." At first, all four women were delighted with their shiny new imported wheelchairs. But within just a few months, all stopped using them.

Wheels of Fortune learned that this low use-rate of donated equipment was disturbingly common. So it sent a team of "social marketing" experts from the North (who did not speak the local languages) to analyze the problem. The experts concluded that "the recipients don't appreciate or care for things given to them free." Their solution was: "Require each recipient to pay at least part of the cost of all aids and equipment." With such cost-sharing, the experts insisted, "recipients will value more and take better care of the equipment they receive."

The four young women see the problem differently, If we were to ask them to analyze and state their concerns, we mfght find that each has good reasons for not using her chair. She would most likely insist that, "If I had a chair that really helped me to move and do things more easily, I would gladly use and care for it!"

Now let us imagine a different scenario. Let us suppose there are community rehabilitation workers who listen to each of the four young women and help them figure out the best local solution to their mobility needs. Together, they may be able to design more appropriate alternatives - liberating solutions that free the user to lead a fuller life in her home and community.

Here we present, briefly, the stories of these 4 young women. Though imaginary, their stories are based on reality. The solutions they find to their specific problems within their particular environments are based on actual innovations developed by concerned people in different parts of the world.

MIRA, in rural Bangladesh, became paraplegic (paralyzed from waist down) as a result of fighting between religious groups in her village. In the hospital, a social worker gave her a wheelchair from Wheels of Fortune. On the hospital floors, Mira learned to move about in her chair. But on returning to her village, she had problems. Traditionally, cooking was done at floor level on a cooking pot called a chula. Everyone ate sitting cross-legged on the floor. In her wheelchair, Mira was separated from her kitchen work and from the family at mealtime. For a while she sat in her chair without working; others served her food onto a board across the armrests. But Mira wanted to fit in better and to contribute more to family life. So she stopped using her wheelchair and began dragging herself around the dirt floor on her hands and backside. Maybe it was not the best solution, she thought. (It could cause severe and infected pressure sores. See Chapter 27.) But it was better than the isolation of sitting in her wheelchair.

Solution: An answer to the needs of village women like Mira was found at the Center for Rehabilitation of the Paralyzed in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The Center is staffed and run mostly by spinal-cord injured persons who seek solutions to their own and other disabled persons' needs. They designed a "low-rider" wheelchair, or trolley to meet village women's need to cook and eat at ground level. First they created several working models. Then, in response to feedback and suggestions from different spinal-cord injured villagers, they adapted and modified the design. The trolley can even be used as a toilet (see page 194).

Because the chair is made completely of local materials and is fairly low-cost, it can be easily maintained at the village level. These low-riding trollies have made it possible for women like Mira to return to their village homes and function effectively.

|

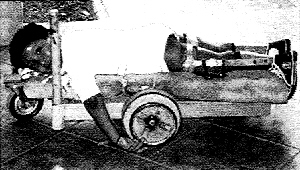

A metal-frame, wood-wheel trolley in Bangladesh. The rubber tube serves as a cushion and also as a toilet seat. |

This trolley has a cushion made of coconut fiber coated with rubber. Firm but spongy, it helps prevent pressure sores (see p.156). |

RITA lives in the mountains of Mexico in a small, pole-walled hut. She broke her lower back when she fell carrying water from a ravine. Like Mira, Rita's fancy wheelchair is of little use at home. She cannot ride it on the rough, narrow trails. Her hut has 2 small rooms for 8 people. The tiny kitchen has a big mud stove and no room to move around in a wheelchair The kitchen counter, also made of mud, is at a height made for working standing up. And there is no space under it to position a wheelchair. There is simply no way for Rita to move or work effectively in her wheelchair. Her stepmother sees Rita as useless and has begun to resent her presence.

Solution: If after her accident, Rita's rehabilitation workers had involved her in thinking through her therapy and assistive equipment, they might have found more useful alternatives. They would have realized how unsuited her environment is for a wheelchair (especially a clumsy, oversized one). Because her injury was low on her spine (L4), it may make more sense to see if she can learn to walk with crutches - or at least figure out a way to stand up to work in the kitchen. To do this, leg braces might help: possibly simple, lightweight ones made from plastic (see Part 2).

To prepare for standing and walking, Rita will need an exercise program (1) to strengthen her arms and upper body, and (2) to maintain or increase the range of motion of her hips and knees. If she can gradually stretch her hips and knee joints until they bend backwards a little, she may be able to stand and even walk (with crutches) without the need for long-leg braces. She can do this by "locking" her legs in a back-knee position, and by leaning her upper body backwards to stabilize her hips. She may even be able to work standing up, with her hands free (without her crutches).

By leaning backwards over her hips, Rita can keep her body upright, even wrth no strength in her lower back. (To prevent doubling forward, her center of gravity must be behind her hips.) With knees bent back, she can bear weight on her weak legs. |

Simple below-the-knee plastic braces prevent foot-drop and help her avoid ankle-twisting on rough paths. A slight downward angle of the foot pushes the knee back, adding stability. |

Rocker-bottom shoes allow a smoother gait (walking). A flat area in the middle of the shoe soles permits greater stability for standing. |

|

With practice, Rita should be able to work standing in the kitchen. A strap around her hips may let her work more freely and securely. |

With effort, she may even learn to walk with crutches on the steep trails. But she will need to develop good balance, strong arms, and not get over-weight. |

Perhaps the best solution for travel on the steep trails will be for Rita to learn to ride the family donkey. |

Luz lives in a crowded squatter town in the Philippines. Before her accident she worked as a health visitor, checking the weight of young children in their homes and giving nutritional advice to mothers. After her accident, she found that her new imported wheelchair was too wide for narrow pathways or to fit through the very narrow doorways of many of the shacks.

Solution: Fortunately, a program run by disabled persons called House With No Stairs (see page 342), has for years been experimenting with innovative designs of lightweight, low-cost wheelchairs. One of these has a horizontal folding mechanism (rather than a vertical "X"). This allows the user to easily make the chair narrower while riding it.*

- ________________________

- * This innovation for pulling the wheels in close to the body in order to pass through narrow doorways has been further developed by Ralf Hotchkiss, a paraplegic wheelchair designer who has spent years teaching disabled groups to make and design locally appropriate wheelchairs. Among many others, Ralf has worked with the House With No Stairs wheelchair building team in the Philippines. For more discussion about this and Ralf's many wheelchair innovations, see Chapter 30.

So after they discussed Luz's needs with her, the workers took her measurements and went to work building her a wheelchair with adjustable width.

For ordinary use, Luz uses her wheelchair at its normal width.(Left)

When she comes to a narrow doorway, she pushes her chair's wheels close against her hips, and passes through.(Right)

Then she opens the chair again to its more comfortable width.(Left)

Thanks to a wheelchair that was designed to help her overcome the barrier of narrow doorways, Luz was able to continue her work and earn a living helping other people.

FARAH lives in the Egyptian desert. Since her accident she has joined a women's cooperative where she can make clothing on a sewing machine, and sell it in local stores. But the cooperative is in another village, about 2 miles away on a sandy, rocky road. The narrow wheels of her imported wheelchair sink into the sand, making travel impossible.

Solution: Farah described her frustration with getting stuck in the sand and rocks to the local community based rehabilitation team. Together they tried to come up with a solution. They thought of putting extra wide bicycle tires on the wheelchair, so it would not sink in the sand. But they could not find tires that matched the wheels of her chair.

So they made a new, simple wheelchair using wide bicycle wheels. For the small front wheels they used thick disks made with several layers of plywood, covered with a wide strip of car tire. When Farah tried her new chair, the small front tires sunk somewhat less in the sand. But they got caught easily on small rocks. The wheelchair stopped so suddenly that sometimes Farah was almost thrown out ,of her chair.

Farah suggested bigger front wheels. But the CBR team pointed out that if the front castor wheels were larger, they would bump into the footrests on making a turn. What to do?

One of the CBR workers remembered a picture he had seen of a "tricycle wheelchair" with a single large front wheel, mounted in front of the footrests. So the team built a "trike" for Farah using extra wide bicycle tires on all 3 large wheels,*

- _______________________

- * There are many designs for tricycle wheelchairs, powered by one or two hands. See Chapter 31.

The trike, powered by a hand lever, was a great success. Farah found it ran well on the sand and gravel roads. She could make it move so fast that it sailed through soft patches of sand without slowing down or getting stuck. She loved it!

In conclusion ... The 4 young women - Mira, Rita, Luz, and Farah - all found different solutions to their different local and personal needs. This was possible because local rehabilitation workers listened to the women and involved them in planning and testing various innovations and adaptations. For 3 of the women, the solutions involved specially designed wheelchairs. But for Rita - who lived where wheelchair mobility was virtually impossible - it meant learning to stand and walk with braces, and riding the family donkey.

Examples from Real Life

While the stories of the four women with their different wheelchair needs are imaginary, they are based on experiences of real women. "Low-rider" wheelchairs or "trollies," such as the one adapted for Mira's needs, are produced for paraplegic women in Bangladesh by the Center for Rehabilitation of the Paralyzed.

This woman in Bangladesh uses a trolley in her home business, raising chicken and selling eggs. Having an income of her own increases her independence and wins her community's respect. Photo by Shahidul Haque for Social Assistance and Rehabilitation for the Physically Vulnerable (SARPV).

Wheeled cots can also be adapted to local customs.

|

In most countries, trollies (wheeled cots or gurneys) are at a height so the person can eat and work at a table. This boy is on a gurney in order to remain active while his hip and knee contractures are straightened. (For more on gurneys and trollies, see Chapter 37.) |

This floor-level trolley, or wheeled cot, was developed by the same program in Bangladesh that builds low-rider wheelchairs. It allows this boy to join his family for meals on the floor. (The boy needs to lie on his belly to heal pressure sores on his backside and to correct his hip contractures.) |

Nothing About Us Without Us

Developing Innovative Technologies

For, By and With Disabled Persons

by David Werner

Published by

HealthWrights

Workgroup for People's Health and Rights

Post Office Box 1344

Palo Alto, CA 94302, USA